Interview

Monumental: An Interview with IBé Crawley

Artist Bio

IBè Crawley, born in 1959 in Danville, Virginia; she retired from traditional classroom instruction to focus on an innovative approach to education. Trained to stitch and sew by her mother and grandmothers, IBè Crawley taught herself to carve stone and wood. She added clay, dollmaking and papermaking, before adventuring into printmaking.

IBè Crawley renovated an 1830s school building, originally built by enslaved black men. It was originally used for the purpose of educating white males on the Epps plantation in Hopewell, Virginia. It has evolved into The IBe’ Arts Institute, a repository for Crawley’s work, which includes carved marble, wooden assemblages, paper and print, as well as quilted narratives.

IBe’ Arts Institute invites fellows, interns and creative-partners to participate in discovering and documenting voices that educate future generations. Collaboration is foundational to IBé Crawley’s studio practice. Whether in residency or in her studio Crawley is energized by being in fellowship with other creatives.

Artist Statement

“ The work I create focuses on colored women, girls and their communities. The fragility of freedom as a state of being and the humanity that I represent in my one-of-a kind books and book editions include letterpress, handmade paper, sculptures, and print making.

The archival research adds to the narrative and structure of the books. As a professional storyteller, my work looks at past and current events. My process, my projects, and finished pieces evolve slowly and thoughtfully.”

IBé Arts Institute exterior

The Interview

This interview is composed of a Zoom conversation edited for clarity and flow. IBé has a lot of wisdom to impart and is a wonderful storyteller so there’s a lot here. There’s much more available though, including a conversation on nurturing your career and pricing your work. You can watch the whole interview at the YouTube link below. Reading or watching, you’ll enjoy your time with IBé!

Blake Sanders: You were born in Danville, VA and attended VCU for undergrad and your Masters in Education degrees. Could you please share a bit of what your childhood was like in Danville? What was your path to college? What was your experience like in Richmond, in the city and as a student?

IBé Crawley: I am from Danville, Virginia. I was born in the s, and I lived through the Civil Rights movement. My grandfather was a civil rights worker. He led a protest. The young people wanted to go to the public library, but they weren’t allowed to go to the public library because it was segregated and they wanted to go to the white library. My grandfather led a group of young people all to the courthouse steps. He led them to the public library and to the parks. As a little girl growing up, listening to the arguments at the dining room table about nonviolent direct action really touched my life.

My grandfather was a taxi driver, and he was very active in our community. He only went to the third grade, but he read the newspaper from cover to cover all week, and he shared it with the neighborhood. He was a very independent man, and his grandfather and his father had been born enslaved and lived through sharecropping. So my grandfather was very determined to be independent and a broker. He bought a taxi and started a taxi stand, and he drove the Black people to their jobs in the factories and their meals, and he really knew the community. When I was a child, I was always in the taxi with him, and I got to meet people in the community and go to the late night shift to pick up people at who were getting off work or going to work. I have a deep love for my community and my community in Danville, where I was raised, and my parents, grandparents, and all the sacrifices they made in the 1960s. My grandfather went to jail. My cousin went to jail. She was beaten by the police. Then to sit at the dining room table for ten years to listen to them talk about their experience, because they were actively involved in a court case that lasted until the 70s.

I graduated high school early because every year my grandma would say, you should take a class in school for the summer or two so that you can get some extra credit, but it was also a way of keeping me safe because it was a safe place to be. So I graduated from high school when I was 16 and I decided I wanted to go to VCU. But we didn’t have any money. My father worked in the factory. I think he made like $5000 a year. He was like, baby I can’t send you to college. My grandfather was like, well, some of his people that he knew from the civil rights movement [might be able to help]. One of the things that he had done is he and my cousin, Lawrence Campbell, invited Doctor Martin Luther King to Danville to assist with the protest because they weren’t getting very much newspaper coverage.

Doctor King came three times, but he wasn’t there on Bloody Monday, and Bloody Monday was the day that the police came out in full force against the protesters. So my grandfather went to jail, but he was represented by a Black woman. She was a lawyer named Ruth Harvey Charity. and I’ll remember her forever. It made me want to be a lawyer. My grandfather Winters said, I want to go to college. She [Ms.Charity] said she thought she could help. So they came up with the money. My father had a cousin who had been to college, and she helped us with some paperwork. That’s how I got into VCU when I was 16 years old.

I really didn’t know what I wanted to do with a degree, but I knew I wanted to go to college, so I did VCU for four years, and I graduated with an English degree, and I was very interested in my community. I worked with folks who were either homeless, I worked in a battered women’s shelter. I worked with children who were in kindergarten. I worked with, men and women being released from city jails and penitentiaries. I created a program where they worked on skill pools to reconnect with their children and their family members. I did a lot of social work. I worked with handicapped adults or adults in wheelchairs, so I felt like I was really getting a deeper understanding of what people needed and wanted. I was learning people’s stories. I’ve always been a storyteller. That’s how I ended up becoming a storyteller.

When I was a child, my great grandmother would always tell stories. As I grew older, I realized that the power of my storytelling is my ability to tell stories about people and the stories that people share with me, and to make sense out of stories. I’m a sculptor and I am a book artist, and what I do is I take stories that I learned from people, the stories I learned from life or from history or from my own research and I try to make them visually something that people can see and touch and feel that they can create themselves. That’s what I do. I tell stories of life that I’ve learned and try to make it visual.

Sho Women in Clay

Four clay tiles

11″ x 36″

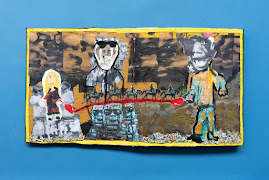

The Book of Jubilee

Collaged Harper’s Ferry magazine images, letterpress

9″ x 12″

2022

B: Before returning to VCU for your Masters in education you worked for several years as a social worker, aiding recently released prisoners and working with abused women and folks with mental health challenges. I can see the influence of this work on your artwork. How did you synthesize this difficult and deeply empathic work into your art making practice?

IC: I think that there are rituals that occur in social gatherings, in social work. In my family, we ate dinner together every night and we also would eat together every Sunday. It was a large gathering so that sense of sitting in a circle and hearing people tell their stories, their concerns, the relationships that develop around food, and the ritual of food, and the daily act of food, what we learn about each other become important to us, the stories that we tell.

I think that going into social situations, the biggest thing was the circle that we formed, that bond and understanding that the people I worked with were not perfect. Often times they had made a pretty bad choice at some point in their lives that caused them to be in a situation where they needed to be in the circle. There is an acknowledgment or an expectation of repair. That’s part of the circle work is repair work. Listening to people talk about how they got to where they are and their understanding of what they need to do to be a better person or to correct a situation or to build a bridge.

I think that that comes through in my storytelling, because when I try to convey to stories to people, I try to do that full circle, that understanding that we are in circle with each other. We’re in dialog with each other. Even you and I happen to be in conversation with each other because of a breach that occurred, and we had to acknowledge the breach. Then we had to say, how can I participate in repairing the breach? That’s the circle process. Whether you’re dealing with civil rights, human rights, or individual family relationships. I think for me, it’s reflected in the work because what I bring to the work is the notion it’s connected to the healing ritual of acknowledgment and repair.

BASH Boats

Clay figures, wood, copper, nails and cotton

30″ x 17″

2021

B: After working in schools for many years you chose to found the IBé Arts Institute. How did your time in education inspire the formation of the organization, and now the gallery and residency? How does it build on your time in the classroom and how does it differ from a traditional classroom experience?

IC: First of all, IBé Arts Institute was an old school building in Hopewell, it was built in 1830 and used as a two room schoolhouse till 1860 when the Civil War occurred. Grant had his headquarters here on this plantation. This is an old plantation called the Appomattox House. It’s the Epps plantation, and it was probably about 2200 acres large. It’s on the James River, and it’s the last largest entry point. The boats would come off the Chesapeake Bay and enter to sell enslaved people back in the 1800s. During the Civil War, it was also used as part of the Civil War hospital. The injured were housed here and in the field out in front of me, facing the water.

When I heard about this property, I didn’t know what it was. I was just told it was a school, and I thought it was going to be a place that I could come and start an education program. I had worked for 30 years as a teacher. I’ve taught everything from kindergarten to college, and I worked with everyone from folks with special needs to the gifted and talented. I had worked in large groups, I had worked in small groups. I had done English and math and science, I had done history, I had done International Baccalaureate, and I retired. When I retired, I knew I had this wealth of skills that was related to storytelling, but related to a practice that allowed me to be able to measure my progress, like in the classroom. As a teacher I was given a curriculum. I had to measure their growth, I had to measure myself as an instructor, and they had to measure me. There was a lot of feedback and data. My last five years, I became a data analyst in the school because I was very interested in looking at how teachers can work together as a group and create a lesson based upon the individual curriculums that they merge together. That’s similar to what we’re doing in the storytelling circle.

I had that experience of the crossover between being an educator and a storyteller and a teacher in theater, in Fairfax my last few years working there. When I retired I knew I had a set of skills. I decided, I live in Washington, DC, there’s tremendous need in Anacostia, which is a low income area where it’s very condensed and there’s a lot going on. There was a real need there. I said, well, I’ll do a little volunteering. I’ll go into the school and after school program, and I’ll work with kids to get them to create stories. I’ll do community projects.

I had a little building that I called IBé Arts, and we’d do Mayday Play Day and invite kids in the neighborhood. They would do arts and crafts and storytelling. I had the sense, I needed to be present in the community and I need to be contributing to the community, and I need to be creating so that the community sees what creativity looks like for me. I did sculpture and I did book arts, and I did a lot of textile work because I learned that as a child.

When I decided I was going to do IBé Arts Institue here in Hopewell, I said I want it to be a space where I bring together my skills under one roof. I wanted to have a place where I could show my sculpture, where I could make my books, where I could entertain people around storytelling, listening to their stories, teaching them, having them socialize, forming circles. So that’s the impetus for IBé Arts Institute. It’s really an opportunity to take a variety of life skills and put them under one roof in one space and interact with community.

When I say interact with community, for example, I built a relationship with the National Park Service. I had an opportunity to work with college interns with them. I built a relationship with the local bookstore so I could do art exhibits in the local bookstore. With senior women’s groups who were quilters, or traveling artists groups who were educators. All of that becomes who I am as IBé. IBé Crowley the storyteller, artist and IBé Arts Institute is the place where everything comes together under one umbrella.

IBè Arts Institute Gallery

B: The notion of creating monuments for Black women was transforming for your art practice. Please share how your monuments have developed over time and how they may relate, or contrast with the subjects and forms we typically associate with monuments.

IC: International Baccalaureate was the last five years of my career. Five years before that, I taught high school American history. Teaching American history, one of the things that I was aware of after having done it for years, is that we tell the same stories over and over. First grade was learning about George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson and then we went to second grade and we tell them about the Constitution and George Washington and Adams, and then they go on to the third grade. We’d tell the same story, but we build on it over a year period. I had an opportunity to go through all of that and the one thing that I found missing was the story of Black people. There was only one story of Black people, that they were slaves.

I didn’t know who these people were who were slaves. They didn’t have last names. They didn’t have faces. They didn’t live anywhere. There was always one image or two images of those Black people that got circulated over and over. So I didn’t even have a sense of what they look like. The same thing was true with Native Americans. I thought that was the most peculiar thing. I couldn’t figure out what these people look like because all I could see were the drawings in the book, and they seem like, were they real? Was this something that was just made up, like Cinderella or Goldilocks? Because when you tell the kids the same story over and over it gets embellished.

I wasn’t really sure what was happening there and why there were no Black people that I could recognize. Like, I look around in my world and I see Black men, but I didn’t see them represented in the history. There was always this other kind of Black man who was either submissive or untrustworthy or all of these labels that we got presented to us subliminally in the textbook.

I’m gonna give you a perfect example.This is one of my favorite people. It’s an image of George Washington, and in it he is wearing a military uniform it’s a portrait of him. In the background, over his shoulder, is a Black man wearing a red uniform and a turban and he’s holding a horse. I was curious so I would say to my students, who is that man behind George Washington? No one knew, and I would talk to teachers about it, but it would be something that was unimportant. It wasn’t listed as something that you needed to know. So I did research, and I found that this man’s name was Billy Lee. He had been George Washington’s right hand, and he had been with him even when he surveyed the Appalachian.

I was really curious about Billy. What happened to him? What did he do? He broke both of his legs. He was involved in the American Revolution and he was with George Washington at every campaign, even the Potomac. Why doesn’t anyone ever tell his story? It was because he was in the background and no one really ever saw him. I saw African American women that way, too. They were in the background, but no one ever really saw them. I wanted to know, who are these people? How did they live? Where did they live?

When I came back here to Richmond, one of the things I was very interested in is Richmond. I had lived here many years ago when I went to college. I knew there had to be this kind of underground slave history. I didn’t know what it was because it was talked about but it wasn’t my major when I was in college, so it wasn’t something that I heard anybody talking about.

When I came back here I was curious, where did the Black people live? On Churchill? Do they live in the East End or the West End? How did that relate to the slave industry? This is my current project that I’m working on. I found that where we have 95, which is the Interstate, and Interstate 64 is like the access covering, crossing the city and it sits up high on these stilts. Sometimes you have to go across the city, but beneath that is The Bottom. In that Bottom is the train station. And then when you cross over Richmond you will see the train station, an old building from the 1800s. Try to imagine Richmond without 95, which was built in 1960 probably or without 64 but just having this model, that’s where the Black people live, right? I was like, wow, well, who were they?

Then I started looking for tax records. I said, well, they must have had addresses. Who paid taxes? What did Black people pay? I did this digging until I found the people, and I found their stories, and I found their wills and I found their deeds. I was amazed because it was like, wow, I found these people and dug them up. I think that’s the power of the story. That’s my current project, it’s called Exchange and it’ll be out in the fall.

I’m really excited about this book, and I’m printing it. That was one of the things that I was going to do when I went [to Hamilton]. I was planning to do a residency because I’m going to do all of the letterpress, and I’ve spent the entire summer creating these blocks. In the last couple of days I’ve just created a new map, just another way of visualizing. That is a whole other thing. If I create the map in my head, where do I put this person in this place and that thing? Once I’ve done all of that in my head, how do I visualize it so that someone else can see it? Then can I go deeper and say, what were the relationships between these people? He did this and she did that, and did they know each other and did their paths cross? So that’s what I do. I tell stories in my head, and then I try to create them into reality. I don’t know if I answered your question.

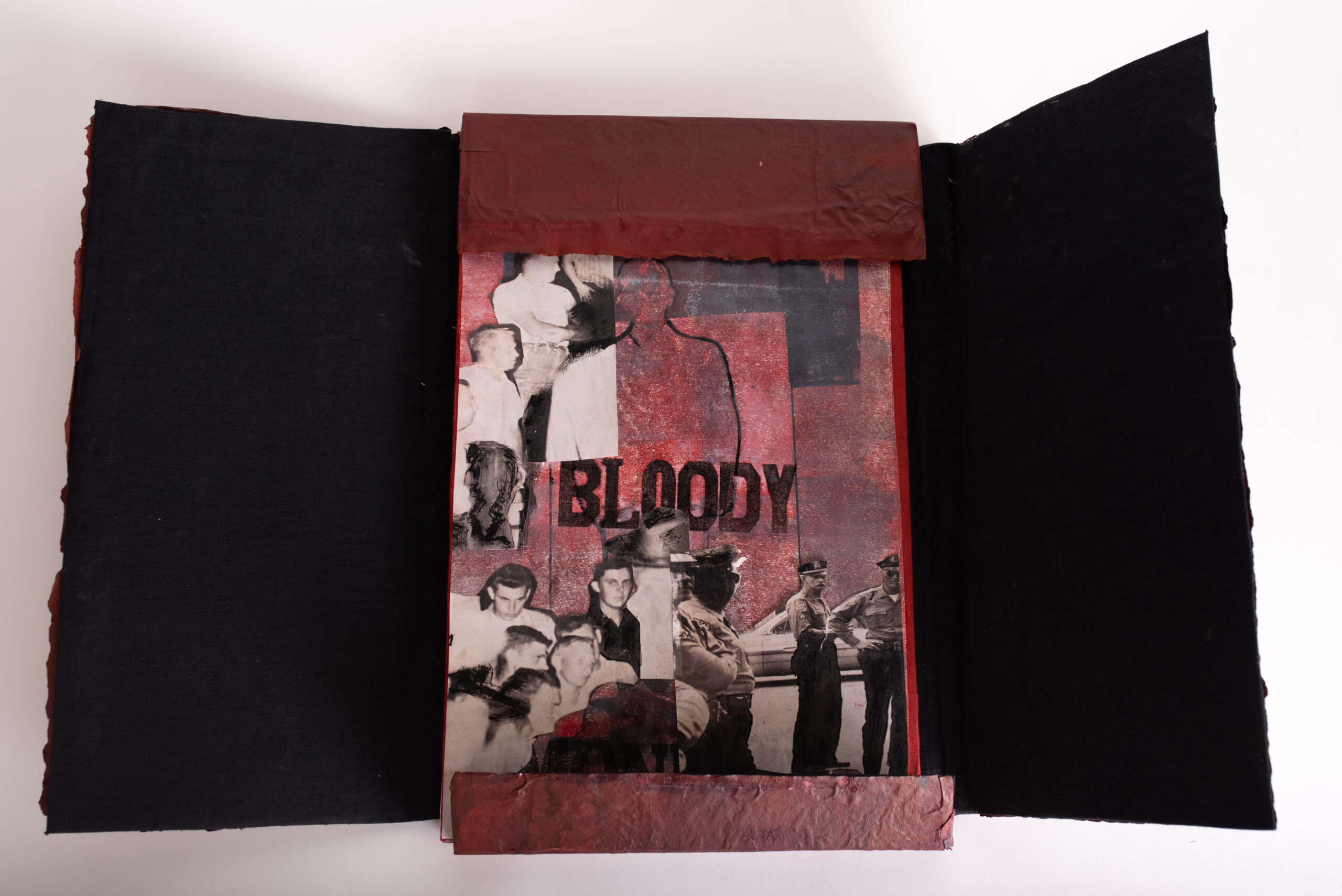

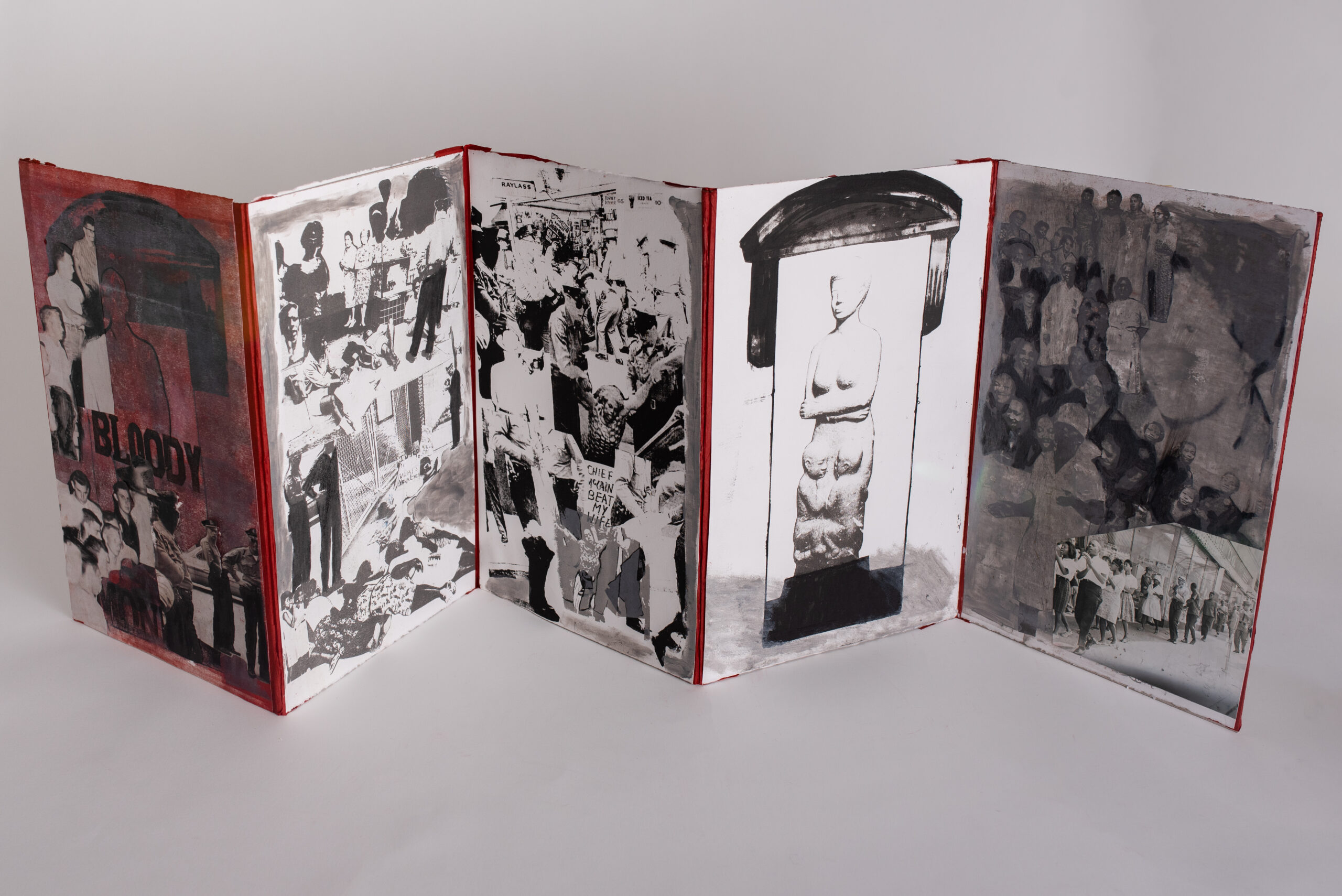

63 Women

Photo-lithography on Stonehenge Paper, with letterpress and digital printing 4 panel accordion structure

11″ x 17″ closed

2024

Image 1: The cover page

Image 2: The accordion book structure

Image 3: The red storage book container of waxed Mary Hark handmade paper

B: That’s okay! Part of what we talked about when we talked the other day was that you were speaking with one of your colleagues at the school, and that helped inspire your idea for the monuments, can you fill us in on that?

IC: Yeah that was a lesson. It was a tremendous learning experience. Representation is so important. One day I was co-teaching with another teacher and a student raised her hand. This was a large 11th grade American history class. She raised her hand and I called on her and she said, Mrs. Grove, do you know who you remind me of? And I thought to myself, that’s never a good question. I said, no, I do not. And she said, Aunt Jemima.

I was thinking, what do I do with this? I said, you have to be really careful when you do public comparisons between people and what we call now anime or icons or images or stereotypes because one is a real person and one is an idea. You have to evaluate all of that. That’s not a good practice of comparing people with things.

My colleague when class was over said to me, I don’t understand why that upset you so much. My grandma had a mammy. Once again, I was struck by the notion of an icon in ways that I hadn’t really thought about myself. I never thought about myself in relationship to Aunt Jemima. But here someone else had and I had to figure out what that meant to them, and what did it mean to me, and how was that the same or different? It didn’t feel good, because it didn’t seem like it was whole, real. The same thing was true with his idea that his grandma had had a mammy. What did that mean, and how did that relate to me, and how does that relate to history and the history that we teach?

I said to him, we don’t do enough with teaching about Black people and women in American history. We tell the same man’s story over and over and over for years, and at the end, that’s what we test them on, and that’s all they need to know. When they don’t know anything else, we give them an out because we haven’t taught them anything. We need to be teaching the range of humanity, not just a simple stereotype or idea.

He said, well, what monuments have they created? What parts of history did they write? What parts of the government did they build? At that moment, it occurred to me that there was this criteria for being included. Access depends upon a key, and we didn’t have the key. We hadn’t built any monuments, we hadn’t written any laws. As far as he was concerned or in American history text was concerned, we hadn’t built the government.

So who are we and why do we matter as women? As people of color? As anyone who’s not a part of that master narrative? And I know there’s a master narrative because we tell it every year for years, and that’s what we test them on, and that’s the master narrative. How do I rise above that? Because I can’t fight that. I can’t fight what the system deems as important, and I can’t make myself important to anyone else other than me. I can’t make my life or my desires important to someone else, and I’m not in charge of that. The President is, seems, maybe. The head of the education department, but I’m not. So what is it that I can do?

At that moment I said, I know that what’s important to me is that I see a representation of me that’s not Aunt Jemima, and even if it is Aunt Jemima, there’s an understanding of Aunt Jemima, there’s a relationship with her, she has value. What does she represent? What did she do? Why are we afraid to confront her? What are we confronting when we deal with her? Who is she and how does she relate to me? All of these images of Blackness,even Mammy, how do they relate to me?

Someone had a sale and they were selling some African American dolls, and they called them mammy, and I make African American dolls. I was trying to figure out what qualified that particular doll to be a mammy to that person. What did that mean? I’m really interested in these images of women and Black people and Black women. The unspoken story that we’re expecting you to get and to understand and to internalize but never speak of.

There’s an expectation that you marry a white woman. Now, I don’t know if you’re married to a white woman or not, but I know that everything our society prepares you for means you will. You may reject that, but that’s what you’re being prepared for. You’ve been prepared for a white woman that she’s supposed to be a certain way. She’s supposed to be Cinderella. She’s supposed to be someone you can dote on. You know, all of these ideas of who you’re supposed to be as a man and how you’re supposed to take care of that woman.

We get all of the stuff dumped on us, but no one verbalizes it. No one really talks to you about it. They just expect you to get it. The same thing is true in our relationship to people who are different from us, regardless of whether they have money, or the color of their skin, or their age, or their ability, or their gender or sexuality. All of these subliminal thoughts going on and we don’t talk about it.

So I’m going to talk about Black Woman because I felt like based upon those experiences, people had expectations of me, and that was something that I fit into. I am Black and I am a woman. Who am I? What do I believe? What is my doubt? How do I know that? Who represented me before I became? How did I get to be me? Whose history am I carrying? Whose history do I pass on? Which story do I tell?

I decided I want to create [work depicting] Black women, and I want to create them in a way that shows this deep love for them. I love my mother. Almost everything I do is my mother. Every time she may look a little bit different. Her features may change, her skirt may change, there may be differences, but there’s that energy the whole time. I’m making a stone sculpture in particular because I’m thinking about this love relationship that I have with this woman who brought me here, you know, and I think that we all have relationships with women, but we don’t explore them. I’m interested in women in that way and that ability to present them with that overwhelming love and regard. That’s the work that I do, whether I’m doing sculpture in stone, or taking a story that I researched and tried to find a way to create it using printmaking and bookmaking.

A Family of Three

Marble

4′ x 2′ x 2.5′

2008

Milk

Marble

5′ x 2′ x 2.5′

2012

B: Please tell us why you chose the marble stairs of Baltimore as your first sculpture material.

IC: Stone sculpture, I love it. First, where else would I find something big enough to create a monument? I’m looking around and I don’t see a whole bunch of stone. That was the one stone I knew about. Going through Baltimore I was like, oh, look at the steps they’re made out of marble. Then I found that there was a recycling place there where people would take the old steps to the dump. I went to this recycle place and I paid $100 for a marble step. The guy delivered it, though I was like 45 miles away, and I turned it on its side and decided this is going to be my first monument.

One of the things I love about being in a relationship with the marble is I’ve done enough research to know that there aren’t a lot of African-American women who carved marble. Mary Edmonia Lewis, who was a sculptor who carved, I believe, Sherman, I know she carved Abraham Lincoln and quite a few other folks during the Civil War. She was part Native American and her father was from Haiti. Her mother was Native American so she learned to do Native American style sculpture, but her mother died. She lives with her father after the end of the Civil War. She does a few more sculptures here and then she goes to Europe and becomes a sculptor there in Rome.

Then the next one is like 1910, and then the next one is like 1940, and then you get to Elizabeth Catlett, in the 40 last years. Mary Edmonia Lewis used marble because she had access, in Rome, to that white marble of Italy. She worked for the Roman Catholic Church, creating sculpture for them, and she would bring it back to the United States in the 1870s and 1880s, and she would sell it all at one time. She was one of the few people who actually carved white marble stone because you have to get it in a certain place.

There are other sculptors who I love that used all different kinds of stone. They might use sandstone, they might use soapstone, they might find some black stone and a whole lot of different other stones because you didn’t have access to that white, Italian stone. You couldn’t get it in volume and it wasn’t readily available.

I found that part to be very interesting. The rarity of the opportunity to work in that particular medium, that in many ways is associated with whiteness because it is white. Sculpture is associated with whiteness. Because most sculptures are of white people. The idea of using something that’s being discarded, something white, to create something that represents Blackness, that’s a real interesting kind of push pull thing going on there. Then to be working with that stone and trying to bring forth that Blackness, and that womaness out of something as hard as stone which women are the opposite, that’s something.

This particular piece? She’s a mother. I didn’t know that she was going to be a mother. I knew this was going to be a Black woman when I started. It’s almost four and a half, five feet tall. I was aiming to create as big a Black woman, as strong a Black woman, as I could create. But as I worked from the top down, I found these two children clinging to her, but she’s looking forward. I’m struggling in this relationship too, because I’m like, why aren’t you like the soft mother looking at your children like you see in most sculptures, doing that loving thing? What’s interesting is you’ve got to listen to your work, to be able to look at your work and see what does the work want to do. What I want to do might not be what or where that print wants to land. I might get a shadow that I didn’t intend to have. I’m willing to allow that shadow to exist and to discover what it means, because it intended to be there, not because I was trying to put it there. Do I feel like a failure when I can’t register something properly? Of course. But the truth is, sometimes it’s important not to be so registered.

Working with the stone and listening to it, one of the things that I got from this stone was like, you don’t know me. You don’t know what I’ve been through. I am a mother who is here to protect her children, not here to coddle her children. I want to protect them so they can grow up and be whole. Being able to hear that energy come from a stone, of what it means to be a mother, I loved that relationship, and I took probably three years to carve that stone. To hear that stone say, I’ve been hiding beneath this step for years with my children, and people have walked on me. They walked over me. They haven’t seen me or recognized me. But I’ve been here all along. To have that come forth out of that stone, and to be in a relationship with energy, because stone is nothing but energy is great.

Stone work for me is a side gig, is a side hustle because it takes so long and I can’t make any money, so I gotta tend to it when I can.

The Abolitionist

Marble

12″ x 24″

2013

B: Your books are organic, well loved objects. Sometimes artist books are so precise you’re almost afraid to crack them open. How does your approach to bookmaking complement your relationship with books and how you want to share them?

IC: I like stuff, I like dirt and I like paper, I like thread, I like fabric, I like glass. I like color, and I’m drawn to stuff. I can walk down the street and see a piece of broken glass, and it’s got a certain color and I’m drawn to it. I want to be in a relationship with that color, but I don’t know how to make it. So I pick it up and I put it in my pocket, and I walk around with it until I get it back in my studio and I put it down I say, oh, I’m going to see how you expand. Then I’ll take all these other little bits of stuff and add to it and wait to see what it creates.

There is a theme I see in my work because I can see it all together. It is the house, the dwelling. It’s because home is so central to who I am and what I think about all the time. The little house that I grew up in. You know, all of us have this relationship with space and stuff. When I’m working with stuff, I’m thinking about my space, and that space is that dwelling. Inevitably I’m always going to create something that relates to the dwelling. So that’s one part of my practice is creating these things from stuff. It can’t be precious because it’s just stuff I found on the ground. The stuff that I cobble together. I can’t make it so that no one wants to touch it. Now that’s on the tactile side.

Then there is the storytelling side of me that’s always got a story that I’m working on, and I’m struggling constantly to figure out what the environment or the character or the interactions should look like and how I can do that and present that in a structured way so that one person at a time could sit and be in a relationship with that story. That’s what’s so precious about books.

Even as a little girl, I loved going back to school because we would get our school books, and I loved cracking the book open. I love new paper and pencils and and being able to write my name in the book. All of those things around books and writing and reading is like publishing. I guess that’s why I find myself so drawn to book arts, because it’s a way of being able to bring all the stuff that I love under one roof, kind of like the IBé Arts Institute.

The Ruled

A dwelling of recycled plastics, and wire in two movable pages

12″ x 8″ book structures

2017

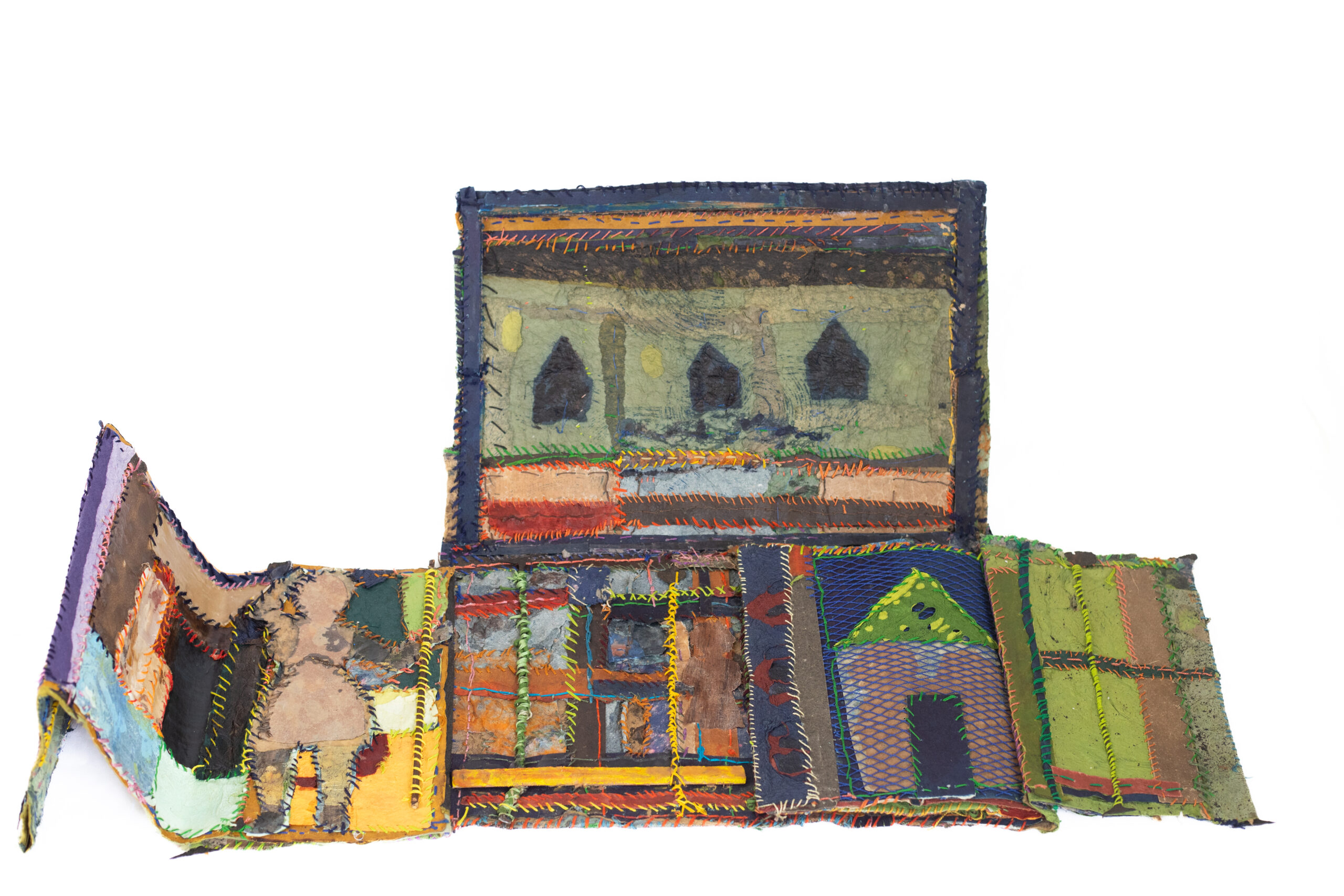

A Dwelling for Herstory (standing)

Handmade paper, screen printing, hand stitching, metal rods

17″ x 28″ portfolio structure

2023

A Dwelling for Herstory (laying open)

Handmade paper, screen printing, hand stitching, metal rods

17″ x 28″ portfolio structure

2023

B: How did a book help make the current manifestation of the Arts Institute a reality for you?

IC: I went to Women’s Studio Workshop to work on a book project about a woman who had been in the state penitentiary of Virginia. She was from near my hometown of Danville, Virginia. The book title is 11033, that was her prison number. I had done a lot of research on her because she was so close to my hometown. I didn’t know her. She went to prison in 1913 or 1914 and she got out in 1921 or so. She had twins while she was in the state penitentiary.

Thinking about her story, I had to figure out how I would represent her. So I created a clay model of her,and I wanted it to be centered in the middle of the book because I wanted the book to be able to stand up.

I sent this mockup to Women’s Studio Workshop made out of brown paper bag. Brown paper bag is one of my stuffs. So, it was made out of brown paper and they asked me what I wanted to do, and I said I’d love to be able to make paper, and to make it look like a brown paper bag. I wanted to create this clay model, and I had this story, this research story that I wanted to put together. They accepted the project and I was there for eight weeks. I created this project with Chris Patron and a beautiful staff of interns and, the ceramicist and it was just a wonderful experience.

I made 52 of those books that were exactly alike, and they were just so well-received. Major libraries bought that particular book like my alma mater, VCU, University of Virginia, New York Public Library, the British Library, Library of Congress, Smithsonian, I mean, all the way to California and Seattle, Washington and museums.

I realized that I had enough to buy this property, but it was in really bad condition. I said, that’s okay. It’s like a sculpture, I’m going to rebuild it. I’m going to take something that’s falling down, that the roof is caving in and the fireplace is falling out, and I’m going to work with a team and we’re going to reconstruct this. It was a wonderful experience. I learned so much about architecture and design, but most importantly about people working with people. Making work about women, having to work with men, in what is typically seen a men’s professions.

[At IBé Art Institute] I have a gallery so all of my sculpture gets to be in one place, and my book work gets to be in one place and those are in old classrooms. Remember this was a two room schoolhouse. One of the classrooms I use as the gallery and I entertain college students and artist groups, and we sit in a circle in the gallery. We’re surrounded by images and stone and wood and paper of women and particularly African-American women. We have conversations about their experiences and feelings and thoughts.

Then the second classroom room I use as my studio. That’s my workspace. Then on the end someone did a little addition that was probably built in 1856 that I call the library. It’s pretty raw. I left the brick fireplace and the open beams on the walls so people could see what this was when I came here.

Then someone added on this little room I call the residency. It has a bed and a kitchen. It’s just one room and a bathroom. I use this as a retreat. There’s no TV, there’s internet. So when people come, they’re forced to deal with themselves because it’s a really quiet space. Like I said, overlooking the James River. This is the way that I’m able to pay the utilities and pay the taxes on the building because I used the book [revenue from 11033] to buy the building, and then subsequent works to do the repairs. So IBé artists who can stand on its own.

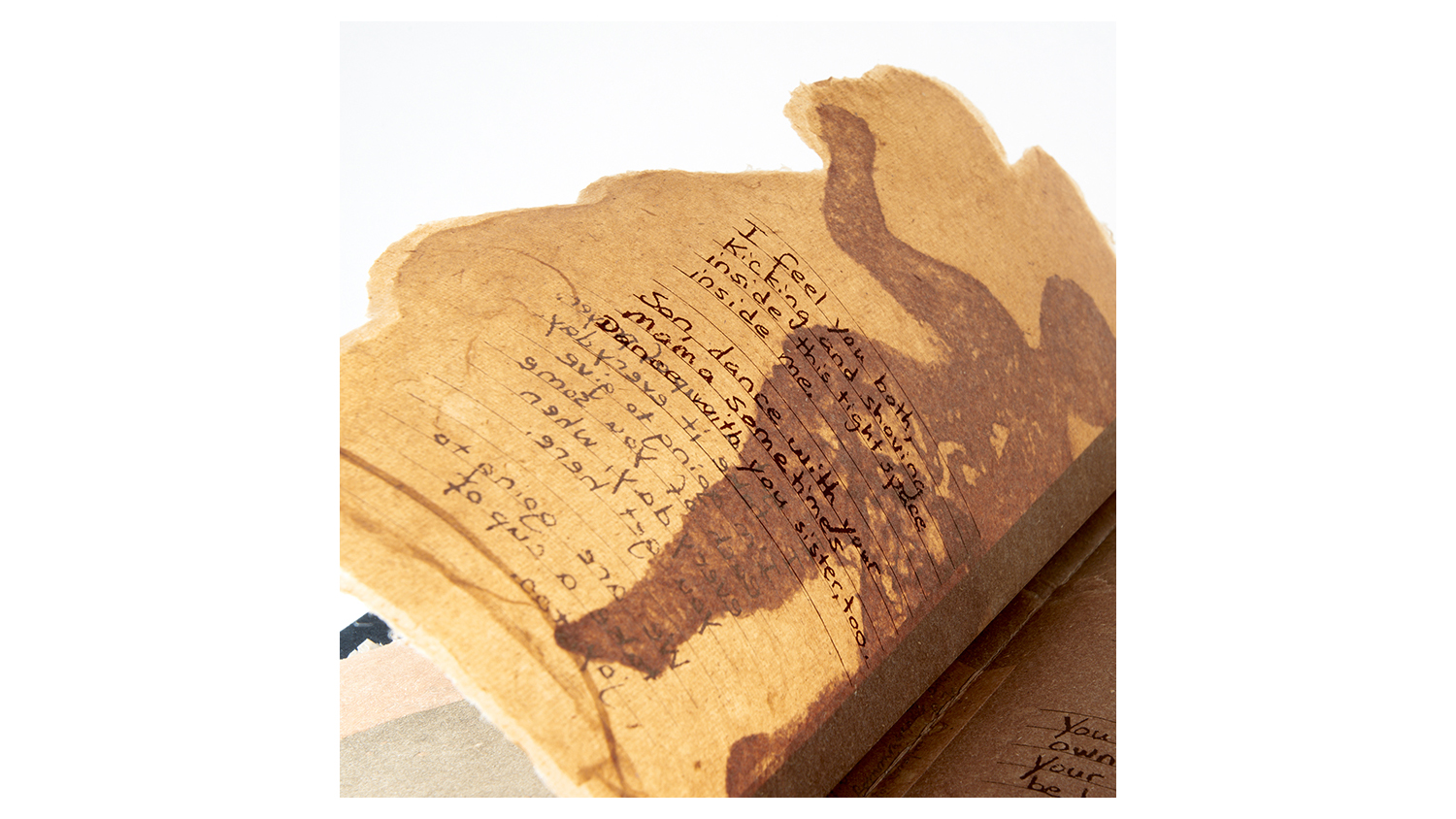

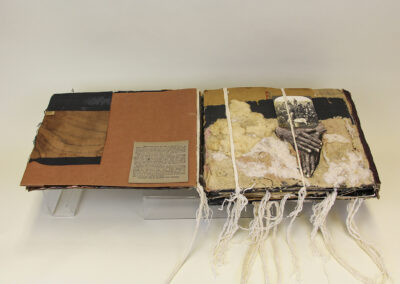

11033 (standing as sculpture)

Handmade cotton, abaca and flax paper, with letterpress and screenprinted text, pulp painting, a clay figure and embedded research documents. Book contained in handmade brown paper bag.

5″ x 9″ codex stitched structure

2022

11033

Handmade cotton, abaca and flax paper, with letterpress and screenprinted text, pulp painting, a clay figure and embedded research documents. Book contained in handmade brown paper bag.

5″ x 9″ codex stitched structure

2022

Image 1: Brown paper bag container

Image 2: Central Clay Figure

Image 3: Pulp Painting of Dance Mama Dance

Image 4: Pulp Painting of Pregnant Woman

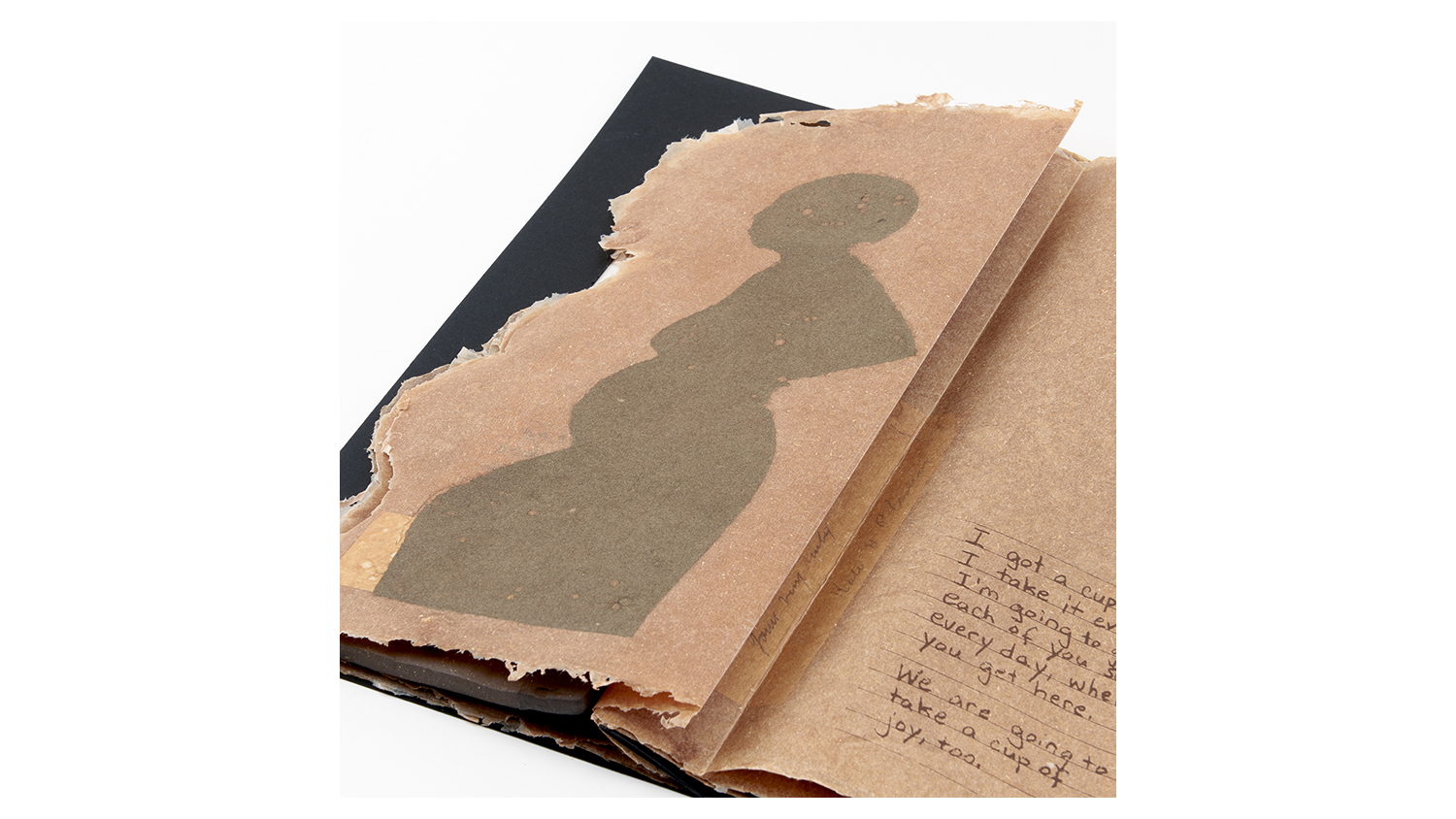

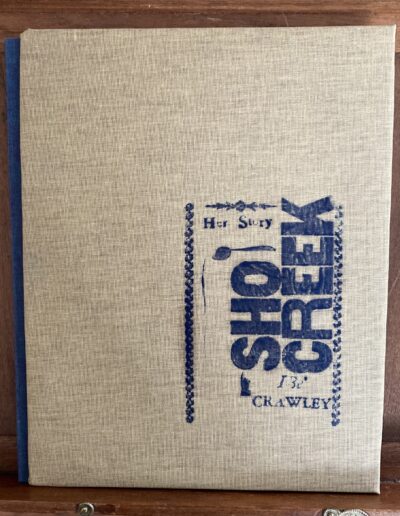

Sho Creek

Pressure printed hand and laser cuts

9″ x 6″ codex structure

2024

Image 1: Cover

Image 2: Page print

Image 3: Inner page print

B: What was your training as a printmaker like? When did you first encounter the medium? How did you integrate it into your creativity?

IC: Back at Women’s Studio Workshop. I learned so much in that residency, it was an eight week residency. It was during Covid so I was the only artist there where they would normally have 5 or 6 artists. They had somebody in the printmaking studio, the etching press, they would have somebody everywhere, but it was only me. That meant I had assistants in all of those studios, who’d studied and were experts in their field.

I had a young lady who was fabulous at screenprinting. She just showed me the ins and outs and I really enjoyed the process. I would have hand written that first book because I didn’t know how to do screenprinting. She showed me how to do that.

Then I left there and I went to Vis Arts in Richmond, the visual arts center in Richmond. They had screenprinting and I started working with Alex there. While I was there, someone else taught copper etching and I had done some copper etching at a workshop so I went back to Richmond to Vis Arts to do some copper etching.

I think that those were my big places, Vis Arts and Women’s Studio Workshop. Then I went to Pyramid Atlantic, and I did some papermaking and some screenprinting there. So those have been my experiences.

Last year I went to Penland and I studied with Delita Martin and Thomas Lucas, and they are both master printmakers. Delita does these mixed media monoprints so I learned a lot from her. Thomas Lucas does photolithography and so I learned photolithography from him.

Then I took a workshop with Julie Chen, another master bookmaker. She’s really a fantastic book engineer. So when you say books that you are just really careful with, I mean, they’re so precise and so measured and exact and her story flows and she’s a master binder, like Chris Patron’s a master binder. For me, they just embody all of these different things from pop-up books, pressure printing and books. I learned a lot from Julie Chen.

I keep recycling people. I find someone who does something well, I learn something from them for a while, and then I go and learn something from somebody else. Then I’ll come back to them because I feel like they respect me a little bit more because they see that I didn’t just stop with them. I went to learn something else and I came back and they can help me correct some of my errors.

I do a lot of pressure printing and I learned a lot of pressure print there with Paul. He’s an excellent letterpress person. Then I went and did a lot of letterpress with Sarah Matthews at Pyramid Atlantic. I also did letterpress with Julie Chen at Penland. So I’ve done quite a bit of letterpress, but then I went back to Paul and told Paul I want you to reteach me to clean the equipment, because I cleaned it with Julie Chen. She’s very precise and so I want to make sure I was getting it right.

I find relearning things as a printmaker is important. Then I was interested in laser cut printing so Julie Chen did a laser cut printing workshop, and I worked with Erin, her assistant, and Stephanie, who’s now at Hamilton. She and I did a laser cut project together.

So I did a few laser cut projects and I came back to Vis Arts again, and there’s a wonderful young lady there named Arissa Lopez. She’s an excellent, laser cut artist. She’s really good on the computer in terms of the graphics. Then I went to a laser cutter here, his name is Ben, and he’s at, Big Secret, he helped me with my maps. I just try to find people who are doing the things that I want to include in my books and get them to teach me. I try to include as many different mediums as I can as a printmaker, because the more options I have the better.

Sometimes something won’t work as a screenprint, I need to do it as a laser cut, or I need to do it as a hand cut. So if you can have different ways to print it’s really important.

A Calling Card

Letterpress printing on commercial paper

7″ x 5″

2021

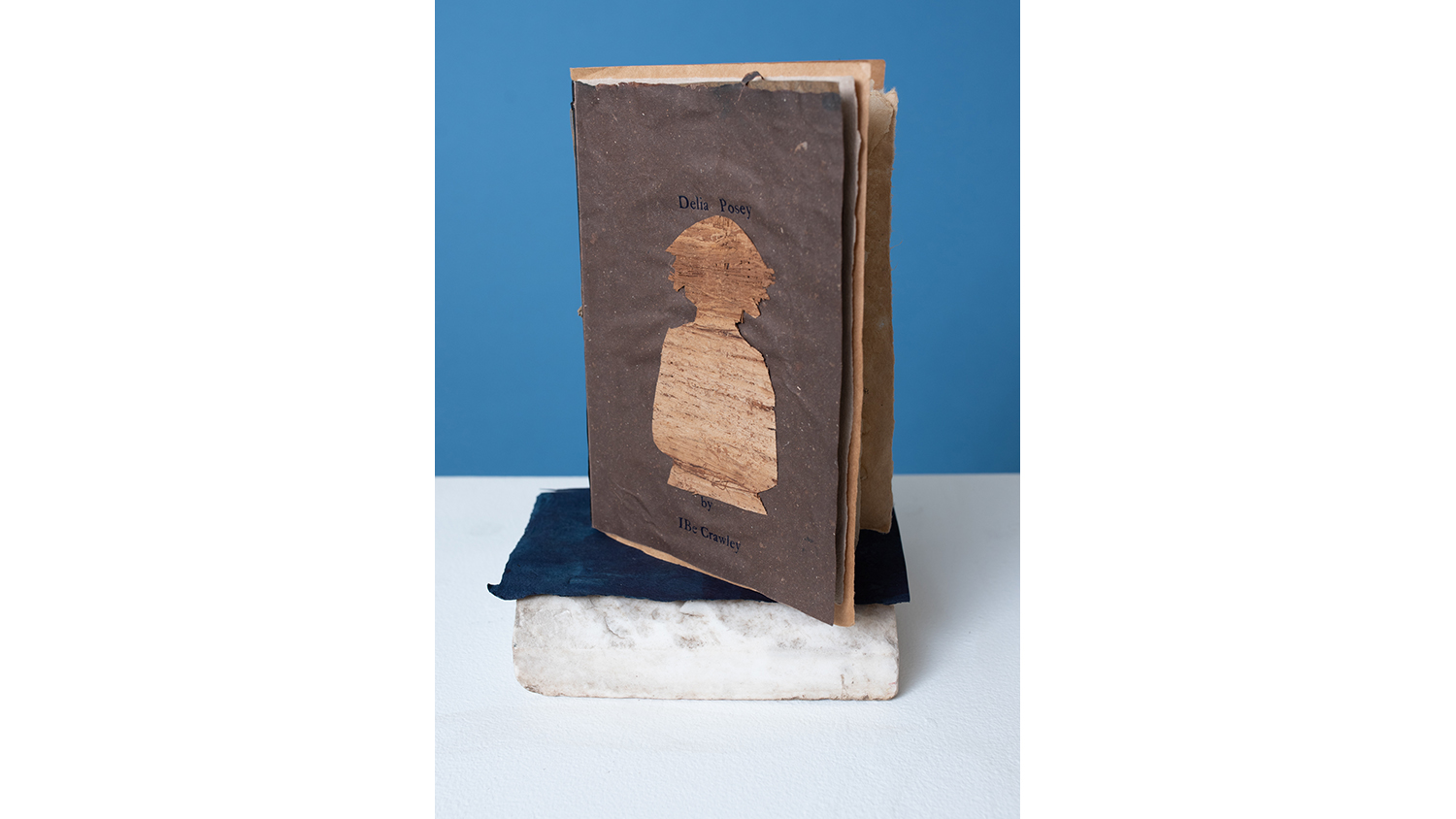

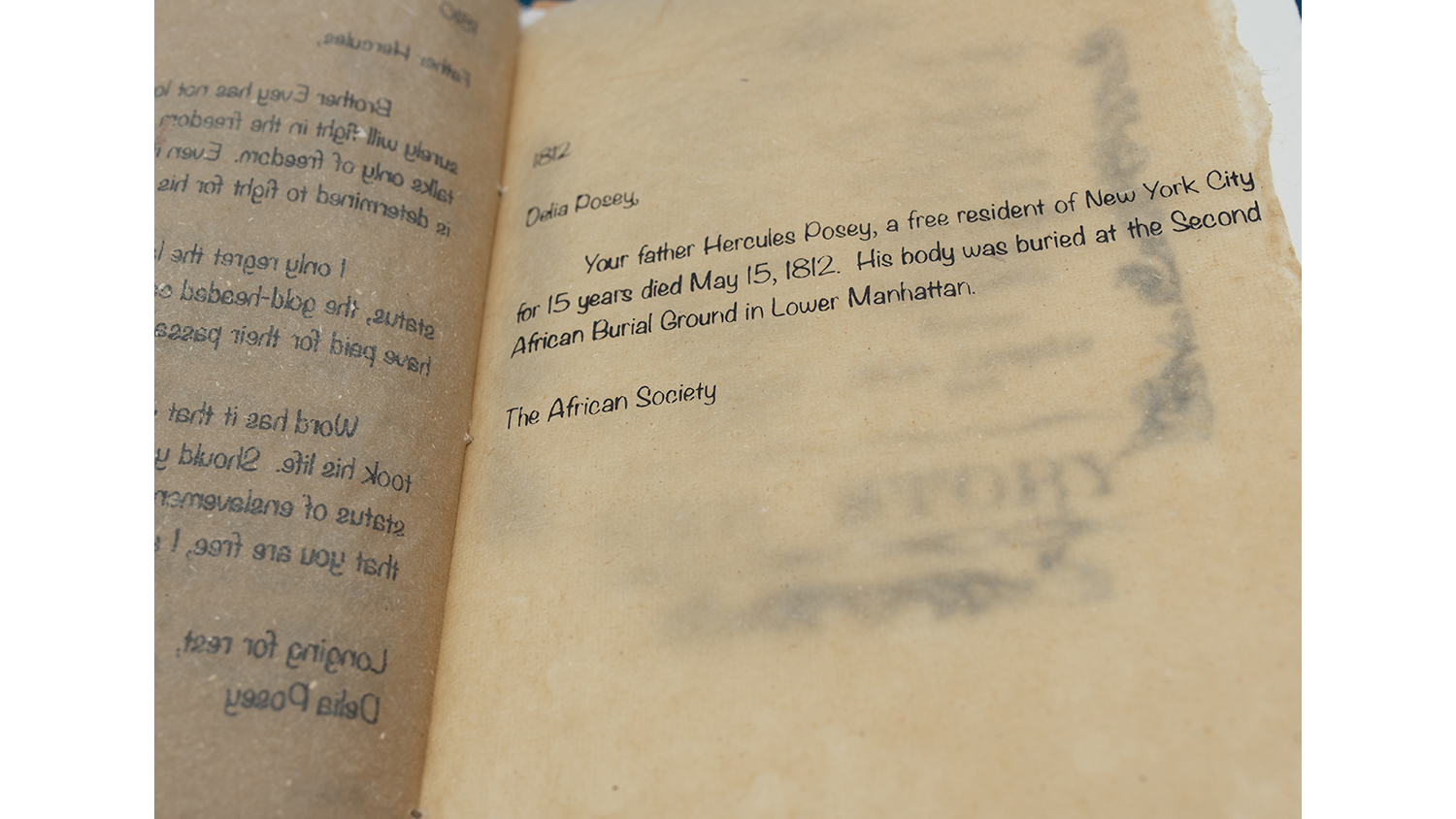

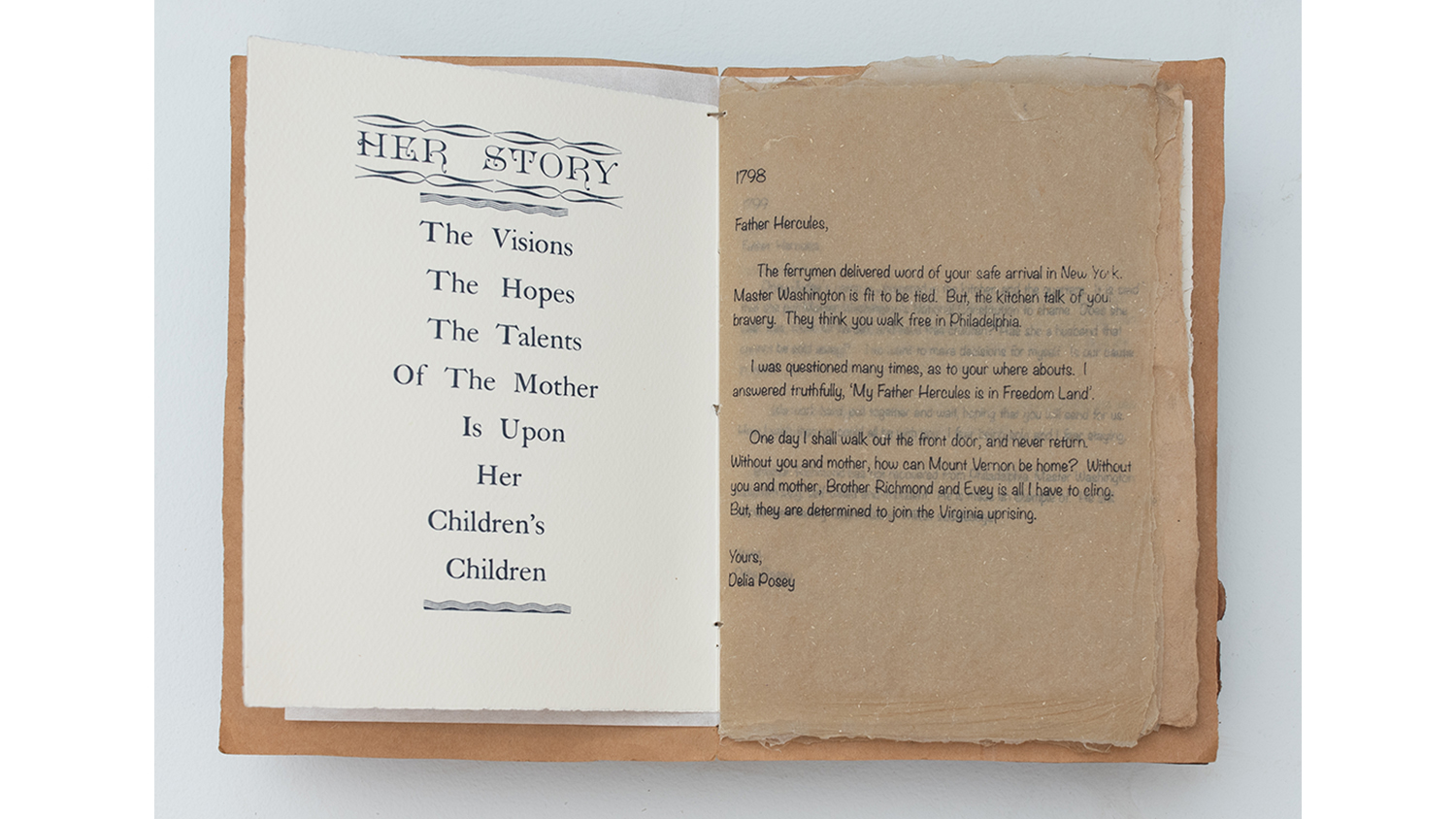

Delia Posey

Letterpress and screen printing on handmade paper, with Mary Hark paper

5″ x 8″ hand stitched codex structure

2022

Image 1: Delia Posey book cover

Image 2: Screenprinted text

Image 3: Letterpress text

B: Summer of 2025 you were scheduled to work through a BIWOC artists initiative at Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum. That experience did not happen. There is certainly overlap between book arts and letterpress and the broader printmaking community, but for those readers who perhaps missed the aftermath of that decision, could you please explain what happened in your own words?

IC: I have this book project and the title is Exchange. It’s the story of women in charcoal Bottom. I’ve been working on this book for a long time. This year I applied for a residency at Hamilton because I wanted to do a lot of letterpress in this book project. So I’ve been printing it and I’ve done about 350 pages. I was really super excited to be able to go there and do the letterpress on their equipment, because on the Vandercook you can print a lot of sheets really fast.

The week before I was to leave for the residency, I received a cancellation saying that I couldn’t come. So I reached out to them, and they just said that because they were reevaluating their initiatives that I could not do the residency and that they would not pay me. The payment part wasn’t a big deal because it wasn’t a whole ton of money, but I said, well, you have it set up on your website that a person can come there and pay $100 a day to print, if they don’t know how to print you will help them and show them how to print. I’ll pay $100 a day. May I come and print? I was told I couldn’t print there at all. So I said, well, can I talk to the board to find out what happened, what were they thinking? What was their conversation? What initiative are they evaluating that I fit into that makes me inappropriate to even pay to print. I was told that they didn’t want to talk to me at the time.

It was interesting because communities of journalism and printmaking and graphic design we’re so many different communities we’re bookmakers and printers and designers and all these different things. At the end of the day, we are artists who archive and document our reality, and because that’s what we’re doing it’s important that we have access to the press. I believe that our larger community was concerned when I wasn’t allowed to print there without an explanation I think it created this uproar. I know it did. We had, I would say on my site alone, maybe 4000 people who watched and engaged with this process of recognizing harm that had been done by my not being able to print there. It was harmful to me because, as I say, it halted the book project I’ve been working on really diligently for two years, so it really set me back. This is work I need to do, but I’m not being allowed to do it. What do I do now?

More importantly than being harm done to me, it was harm to the larger printmaking community who really took offense because we’re living in a time where people associated with media feel that they are being censored. They don’t have freedom of expression, that they don’t have freedom of the press, or freedom of access, or freedom of communication, or freedom of information. There are barriers being erected to prevent us from doing what we do, which is documenting and archiving reality. I think that that’s one of the reasons that folks were like, hey, wait a minute, you can’t just go around denying us the right to a free press.

The expectation was that Hamilton would be a free press because on their website, they say you pay a hundred dollars to come there and print and that they would teach you to print if you didn’t know how. It seemed like an injustice, not simply because they’re saying we can’t afford to pay you, not because they’re saying we don’t want that particular program, but because they’re saying you cannot use this place.

I approached it with my grandfather in mind, and he would have said, and he did say to me in my sleep, this bridge is not built yet. You have to cross. You have to go there. You have to be engaged in this repair. I’ve come to understand that a break in the commitment that Hamilton had made with the print community–that it would be an access point to our democracy–is something that has to be repaired. I think that that just speaks to that larger need. We have a real need for people to have access to the press right now.

It is amazing to me, it’s like an out-of-body experience. That [family experience with protest and civil rights] was years ago. Here we are, years later, still trying to get what we believe are our basic civil rights. Freedom of the press, the freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion. That is a civil right that was guaranteed to us in the Constitution. It’s so important.

As I said, my grandfather read the newspaper. He had a third grade education. He read the newspaper from cover to cover and shared it with our neighborhood. That’s how important the press was and continues to be. I feel really honored to be a part of the community.

My grandmother had two friends and they lived, I think in Lynchburg, Virginia. His name was James and his wife’s name was Pat, and they had a print shop. I don’t think I’d ever met anybody else who had a print shop. They worked together and I went there, and they were someone my grandmother was so proud of. Thinking about my grandparents and how important literacy was to them and how they equated being smart with, not good grades or even the type of job that you had, but with your ability to read and digest information and participate in a discussion in a reasonable way, and argue at the kitchen table and argue your perspective and listen to others.

I think that’s what we’ve been struggling to do, all of us who are in the press is to present a perspective, not the only perspective, not the best perspective, just a perspective so that all the people sitting at the table with us have more information and that we share it with them from our perspective. That’s what I think my grandfather would say, that in this moment this is just a continuation and that’s what I felt like he was saying to me when I was there [at Hamilton] is you have to move forward with this without fear.

When I went to Hamilton, I saw Stephanie and I knew she was so disappointed that the residency didn’t happen. I wanted her to know that I’m not holding any animosity towards her or towards the museum, because those people make decisions and they’re not always the best decisions. It may not be the best for me and it may not be the best for our community, but they made a decision and I want them to do better, but what I really wanted to do was just show up just to say the press is going to continue to show up. Even though the president or the vice president or the secretary of state may say that particular person can’t come in here, we’re going to show up just to say we have a responsibility to communicate with our community what we see. We’re going to come in nonviolence, we’re going to come peacefully, but we’re going to come because our community deserves the right to exist, the right to assembly, the right to speech, the right to understand decisions that are being made. Those are my big ideas.

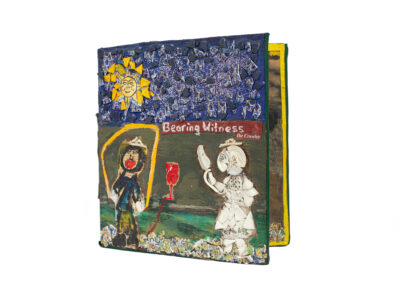

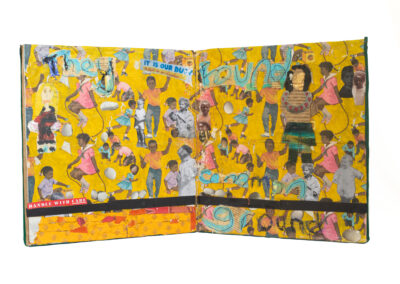

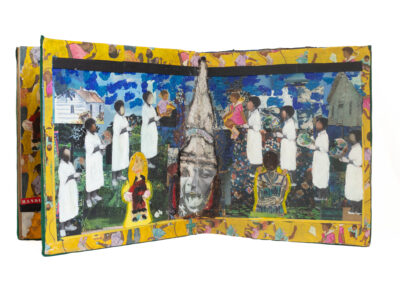

Bearing Witness

Recycled paper, drawings, broken china cups, plastic, paint, and tin

12″ x 12″

2020

Image 1: Cover Page

Image 2: Children as Witnesses

Image 3: Women as Witnesses

Image 4: The Red Line

B: You mentioned in our first chat that you have some new irons in the fire. What’s next for you? What are you excited about that you can share with us?

IC: Well, I will say that one of the things that I’m involved with are a variety of groups of people. I have an association with the African American Craft Alliance. It’s a wonderful group of senior women who are artists in Washington, DC, and they have done beautiful documentary work on the history of African American doll makers, or the history of African American puppets, or the history of African American fashion. These are predominantly seniors, and I’m just so proud to be a part of them and to watch what they’re doing. Every opportunity I get when they have a new project and they ask me to jump on it, I’m like, okay, what’s my role? How do I do this? I’m always there to do a little bit of research, so that’s what I’m going to do. I’m gonna do a little bit of research with them, and then I’m gonna sit back with whatever it is that I am able to grasp out of my research experience, and I’m going to ask myself, how do I use it intentionally to tell another piece of our American story?

I do want to end with talking about my newest work. Which is Exchange: Shockoe, Richmond, 1856. I’m excited by it because it allowed me to create an environment, but I could not see that haunting me. I knew it existed, but I could not see it. And one time I created it using the historic record and I could see it, and I could put houses in a particular place, and I could create this map based upon historic documents that don’t exist now and have not existed for a long time. I felt like, wow, what an amazing way to take the past and bring it to life. So that’s what this book Exchange is allowing me to do. It has a variety of printing techniques, from laser cutting to hand cutting to pressure printing to letterpress printing. An amazing array of printing techniques and I will be presenting it at Codex in February. I will be on a panel there, and I’m really excited. After that, I hope that maybe you and I can show all of the images from it at some point in the journal.

My Cotton

Recycled photographs, cotton, leather, and stitching

9″ x 12″

2018

Image 1: Cover page

Image 2: Introduction page

Image 3: Book page