Interview

Maritza Davila: The Next Chapter

Coordinator’s Note:

In this edition we check in with Maritza Dávila. Some of you may recall Maritza lost Atabeira Press, her home studio that she’d generously opened to the Memphis community, April 23, 2024 in an electrical fire. SGCI shared about the fire in the spring and we’d like to continue to support Maritza as Atabeira is rebuilt. If you would like to help, you may visit Atabeira’s GoFundMe page:

Maritza Dávila is Professor Emeritus at the Memphis College of Art where she was professor of fine arts and the head of printmaking. She began teaching there in 1982 and received the prestigious Klyce Family Fund Benjamin Goodman Faculty Award in 2018 for her long service to MCA. She conducts workshops and teaches at the University of Memphis in addition to exhibiting her work worldwide.

Professor Dávila has exhibited around the world and has works in collections in the United States, Europe, the Caribbean and Asia. She has received awards in the United States, Puerto Rico and France. Her work is included in collections at the National Library in Madrid, Spain; the National Library of Paris France; Taller ACE of Buenos Aires, Argentina; Museum of Art and History at the University of Puerto Rico; and the National Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., among others.

She is owner of the Atabeira Press studio and has collaborated with poet Kay Lindsey and visual artist Indrani Nayar Gall from India on various art projects. She was also a visiting artist at University of Bilbao, Spain in 2011 and the School of Fine Arts of the Institute of Culture of Puerto Rico among others. Residencies include Taller ACE in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2011 and Illinois State University’s Normal Editions in 2016.

As part of her research, exhibitions and in the making of her work, Professor Dávila has also traveled to Spain, France, Poland, England and Japan.

Artist Statement

The thread that runs through all my work is ancestry — the collection of inseparable qualities that, through blood and culture and beyond our ability to control, make us who we are.

And while we may not be able to consent to the qualities of the past that have shaped us, we do exercise choice in how we regard our essential selves.

In my work, the view to ancestry is represented by memories that are woven or contemplated through symbols of passage: windows, arches, doorways, gates. What we see, remember or pass through includes elements of family, culture and religion as well as social, racial and gender facets of life. In a word: Identity.

Each of us connects at all these levels through experience that unfolds with increasing complexity as we grow older. Even as those moments differ from family to family or from person to person, the experiences become a part of our essential selves.

My artwork reflects these experiences framed within frames. Exteriors blend with interiors and geometric shapes contrast with the organic to reveal shadings of womanhood, home relationships, environment and roots. Color and texture create an atmosphere of emotional and spiritual evolution.

Some of my work deconstructs and redefines my past and present. Images I’ve used are cut and reassembled by weaving or collaging, sometimes arbitrarily, sometimes deliberately.

My work engages the diverse elements of printmaking as well as collage and painting. Whether in two-dimensional mixed media works or dynamic three-dimensional books, there are endless ways of expressing the mysteries and power of ancestry.

Capilla Ancestral (Ancestral Chapel)

Silk aquatint

46″ x 40″

2013

The Interview

This interview is composed of a Zoom conversation edited lightly for clarity and flow, and supplemented with a few written responses.

If you would prefer to listen to the Zoom chat you may access it below. It’s worth it to hear the harrowing tale of the Atabeira fire in Maritza’s wonderful voice!

Interview Audio

Blake Sanders: You came to Memphis in 1981 then began your career at Memphis College of Art in 1982 after studying, then teaching in Puerto Rico and New York. What initially attracted you to the city? What has made you choose to stay in Memphis in your semi-retirement?

Maritza Dávila: My husband’s family was residing in Memphis at the time. We had been living in New York with a baby who was born there. Neither my husband or I have family in New York City, and we both came from relatively large families. With that in mind, we decided that moment in New York City was over. So having a child and being close to at least one set of relatives was a decision taken for the sake of our new family. The other option was going to Puerto Rico, but that was a little bit more difficult for my husband, since he did not speak the language or was familiar with the culture. You know me being living in the States for seven years, it was just another transition to make rather than to go into the deep end.

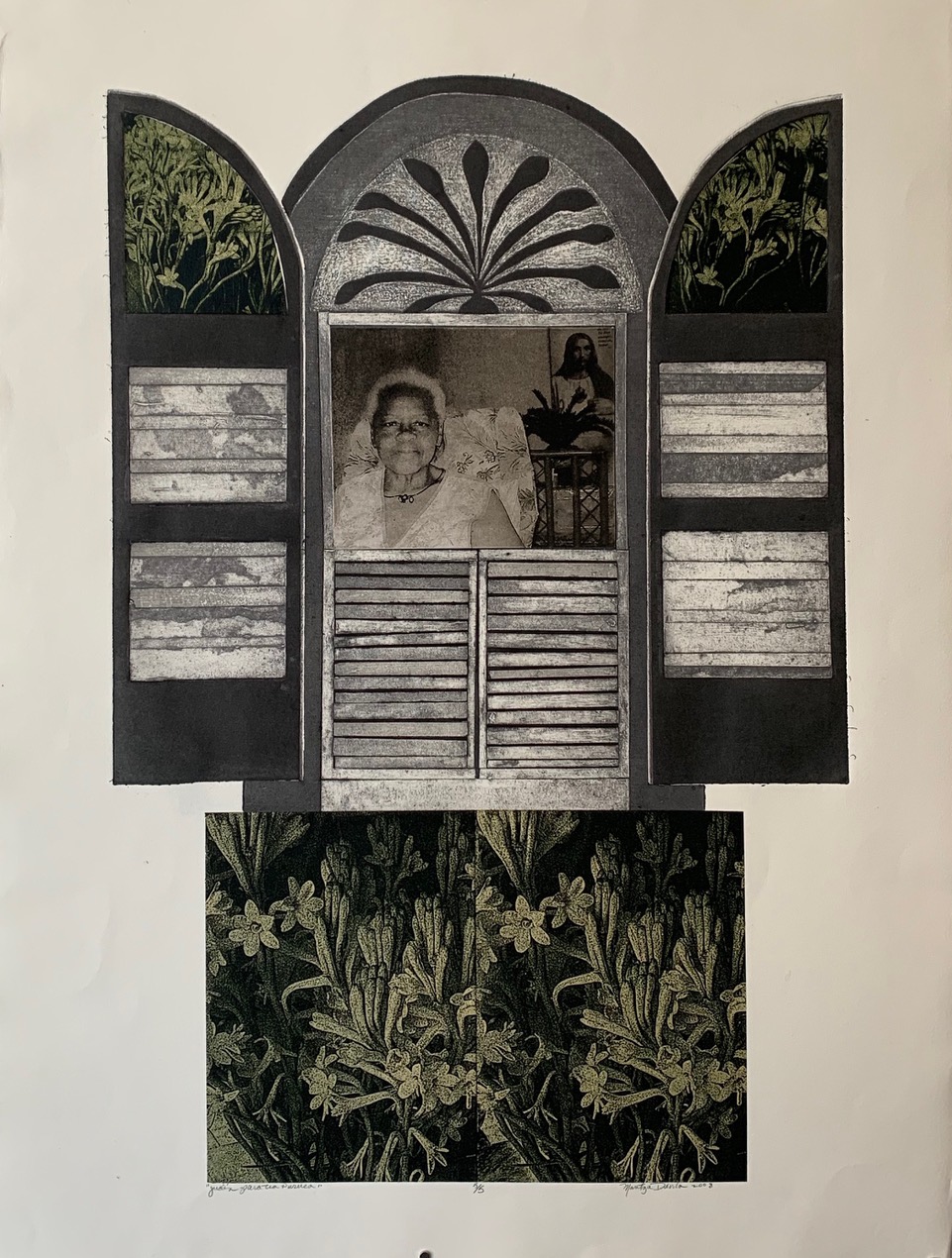

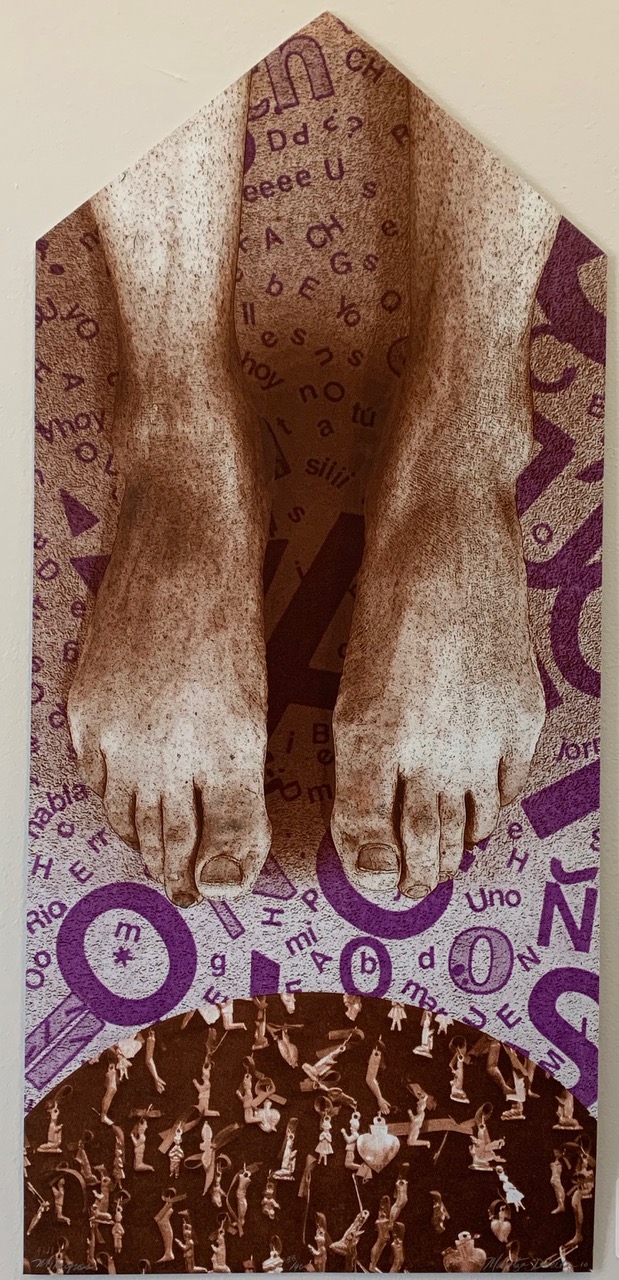

Hola!

Collagraph, silk aquatint, digital, screenprint, collage

26″ x 52″

2011

B: You said that John got a job for the newspaper. What does he do? What was the move to Memphis like for you?

MD: My husband is a journalist. He was working for a local paper in downtown New York City. So, after the baby was born his job was finished with them. My job was finished, too. I was teaching part time at the Museum. Natural History. But that was not a sustainable position that was enough for us to make a living.

In one of our visits to Memphis, I guess it was to baptize our baby, he had an interview for the local paper. And so, on the way back we received a call that he got an offer for a job in Memphis. So we decided to move to Memphis with the idea to be Memphis for a few years, and then move on to another state. I think we were looking to go to Seattle.

So it ends up that we move to Memphis. I started working the following fall at the Memphis College of Art. So we ended up staying. This was 1981 when we arrived with an 11 month old baby and we’ve been here since. Memphis has become my home. You know, even though, with all the misgivings I have with anything related to the South and the politics of race in the South. For some reason it was easier for me to fit in Memphis than it was for me being in New York. It’s very ironic. Many people, especially African Americans, do not understand that. The reality was that I did not fit in a box in Memphis. In New York, I was already in the box. With all the prejudices and ideas that are related to being inside that box. My accent was something that in a way helped me out in Memphis. I discovered people were curious about me. They did not have this idea of who I was already. They wanted to get to know me, and every time you start from that point it’s much easier to interact with other people rather than to struggle to take down all the misconceptions they may have about you.

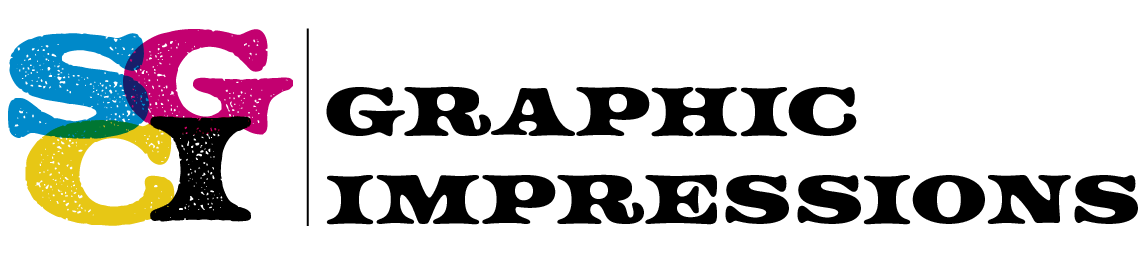

Jardín para Tia Puruca (Garden for aunt Puruca)

Silk aquatint, polymer photo gravure

30″ x 22″

2008

Paisaje espiritual (Spiritual Landscape)

Accordion structure book print, collage

24″ x 56″ x 9″

2023

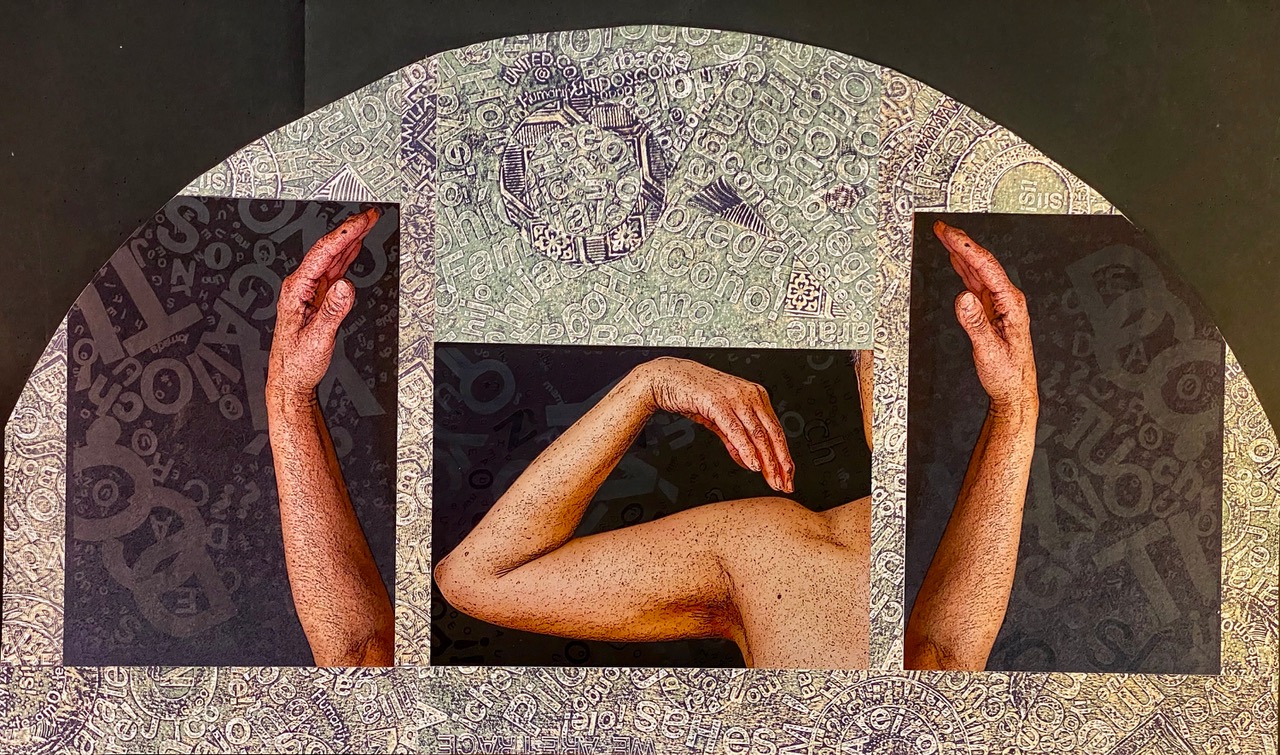

Mapa de una identidad,( Map of an identity)

Silk aquatint, collagraph

Triptych, 30″ x 22″ each panel

2016

Dialologos durante pandemia (Dialogs during the pandemic)

Digital print, screenprint

24″ x 43″

2020

Somos Uno, (We are one)

Silk aquatint, screenprint

30″ x 35″

2020

B: You were professor, then professor emeritus at MCA till its closing in 2020. Could you share a bit about the program you built there? How have you extended that legacy to your continued teaching at University of Memphis and beyond?

MD:

Well, when I got hired at the Memphis College of Art I was hired to teach drawing first and to be a technician in printmaking. They just gave me that position because the professor in printmaking was still there, but I never met him. He was this person who was there but isn’t. He wasn’t available to anyone. It was very strange.

When I got there I encountered a very traditional program, that this professor was in charge of for a long, long time. So the following year they decided to get me to teach some courses. I was an adjunct at that college for a long time. I called the President who was there then who said that since my husband had a job, they didn’t need to hire me full time. You know, you’re here, you’re not going anywhere, therefore why are we going to offer you a full time position, even though I was teaching a full-time program. I was teaching two courses in printmaking, one course in foundations. That is a full program. Then after that I was head of the area in charge of all of these changes. I mean it was just ridiculous. I used to tell the President, I have a job I cannot afford!

Milagros (Miracles)

Lithograph

30″ x 31.5″

B: How long did it take you to convince him to get you to full-time? What was a priority as you established your print program?

MD: It took a new Dean and a new President. I had to convince them I am giving this a hundred, even being part time, because I have never been a person to give half of anything. So they realized she’s committed. She wanted the program. She’s already started changes on the program, you know. So therefore why not pay a salary and tenure for someone who already has proven herself for the past maybe ten years.

Before that I was interested in the print community. I I was already going to SGCI conferences, and I’ve been noticing all these programs, and they wanted me to teach more courses like screenprinting, with all the oil based cleanup and materials, all of that stuff. You know what I’m talking about. I told them I can teach it only if you send me to this workshop in Minneapolis about water-based screenprinting.

I had heard about water-based screen before I started at Pratt Institute in 1975. They were already talking about it. People didn’t know a lot but they were troubleshooting the problems of working with monofilament screens you know, screens clogging, and dealing with the cleaning. I saw all that happening. Then this particular lady in Minneapolis has figured out the inks. So they were already in place. The products and the materials, and they were answering to the problems and misgivings of people moving from oil-based, to water-based.

So I got the program started. I said we have to start from scratch. All the oily screens, all the rubber squeegees, we have to get rid of them. So I started with that. I followed that with non-toxic printmaking. I went to Canada with Keith Howard. He was teaching out of the University of Saskatchewan. I took the first nontoxic workshop with him. I started with polymer plates, with solar plates and I just keep rolling with that. I was the first in Memphis to use Akua, to use solar plates, and use non-toxic, trying to do as much as possible, except for lithography. Everything else was nontoxic, and even when we were using regular etching inks I started cleaning up with cooking oils. So I’m talking the eighties when all of this took place.

I noticed I was getting a lot of skin problems. I became very over sensitized with everything solvent related. I took the philosophy that in order to make art for a long, long time you have to take care of yourself and minimize everything that contaminates our bodies and makes us sick. Plus, I hear all these horror stories of my artist friends in Puerto Rico, not being able to do print techniques anymore because of cancer, asthma, dermatitis, all of this stuff. So I was really concerned about that and that’s something that I really specified with my students. You want to be sure that you know what it is that you’re working with.

It’s amazing even to this day my University of Memphis students they started with water-based screenprinting, but in intaglio, not so much, even though they, started with electo-etch. There was a setup for electro-etch. I added to ferric chloride. So we now have different possibilities in terms of etching. I also started bringing in Akua colors, which are not my favorite, but for certain things like monotypes and stuff like that, you know, especially for beginners and cleanup stuff I prefer to use that with the students.

Many of the students at the University of Memphis have no idea about MSDS sheets and what they’re for. So part of the assignment is please find all the materials that you use, get those sheets and read what the components are, what they do to the body, and how to clean them up. They think well, it’s drawing, therefore, what’s wrong with drawing aside from the dry pigments and all that stuff. It’s my job to make them care about what they’re using and how it will affect them. I actually start the class with let’s talk about materials that we are going to be using. Let’s talk about all the materials that you use on your own. You can contaminate yourself by touch, by everything that goes through the skin, so that’s part of it because I want them to learn to wear aprons and gloves, which I never did when I was a student.

So in part, I just moved that knowledge [about non-toxic printmaking] from the Memphis College of Art into the University of Memphis. Now we have another full-time professor that is also very knowledgeable about all of that. So I feel like I’m supporting him, and he supported me in terms of making the healthiest area possible to teach and for the students to create prints.

The program that I built at MCA, was my pride and joy. It helped me share a better understanding of printmaking as an art form to other people outside MCA. It gave me the opportunity to teach my students how to create prints in a healthier environment for themselves and more importantly gave me the joy of experiencing the students grow as creative people using the medium. My love of teaching is being fulfilled now by being an adjunct at the University of Memphis.

Alma de una ciudad (Soul of a city)

Accordion / pop up book construction, collagraph, screenprint

7″x 4.25″, open to 18″

2023

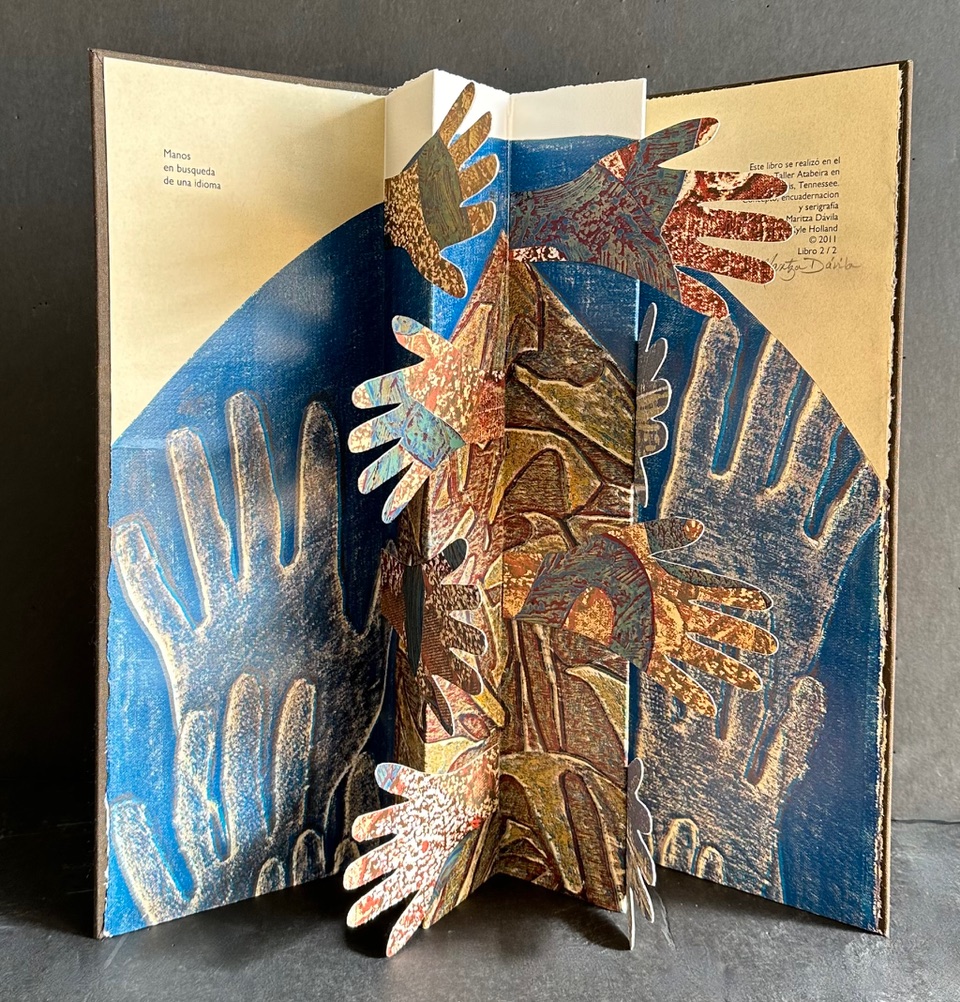

Manos (Hands)

Accordion / flag book structure Collagraph, screenprint

7″x 4.25″ open to 18″

2011

B: Surely that means that you’re making it so that they are starting healthy practices once they’re out in the world. And obviously those green techniques have made it easier for you to set up a studio at home, as well.

MD: Yes, I have very few oil-based, but I have a lot of soap washable inks. I tell my students, please do not call them water-bases because they are not really water-based, they’re soap and water soluble. So they trying to wash Akua with just water, you say, hey, you’re gonna be in trouble because those are soy-based. If they want to try some of the other British inks, well, they’re different with a different kind of oil that cleans up with soap and water, but they are not water-based. I’m so glad that they come in with more and more alternatives for us printmakers.

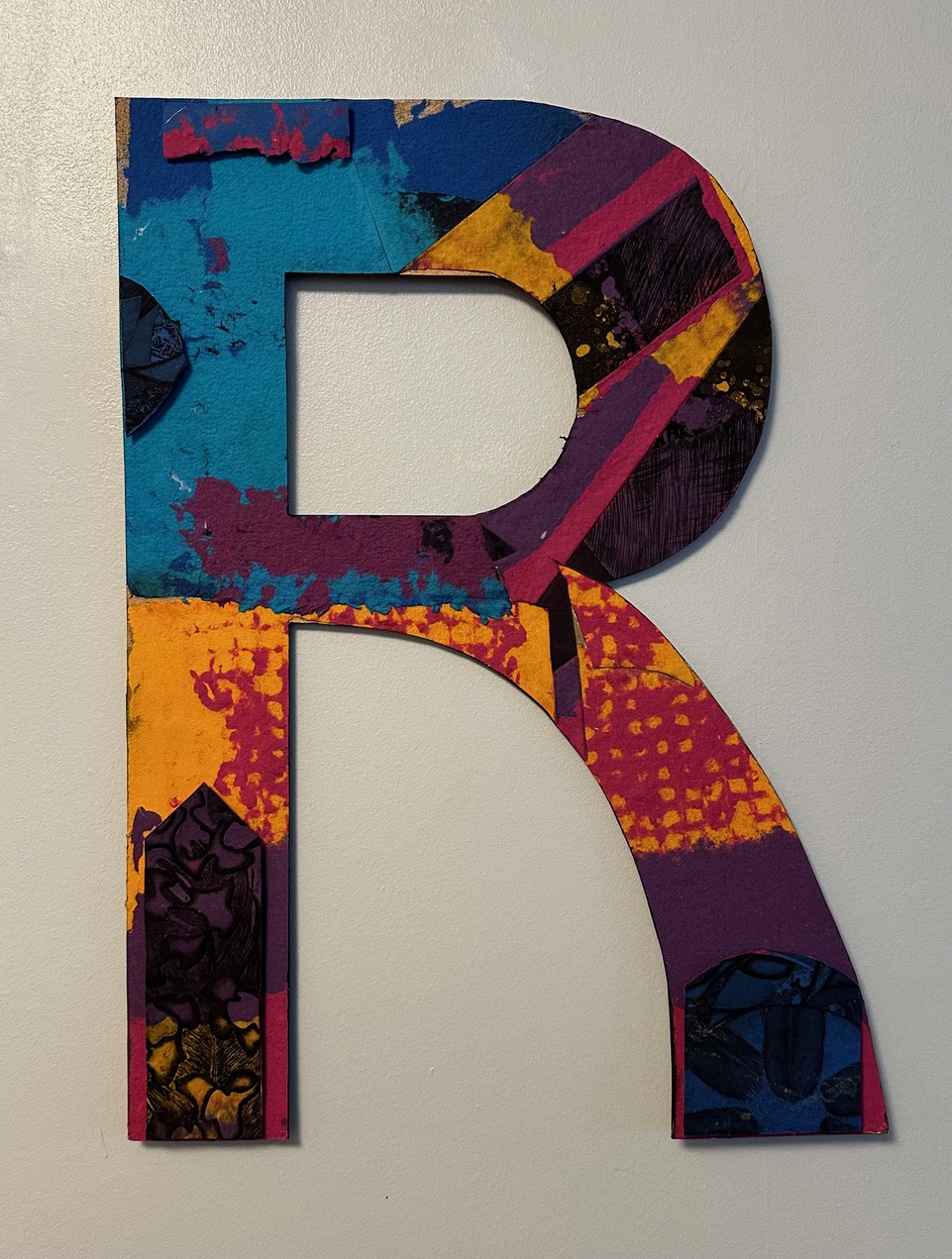

R

Mixed media, collage, handmade paper, intaglio

24″ x 18″

2024

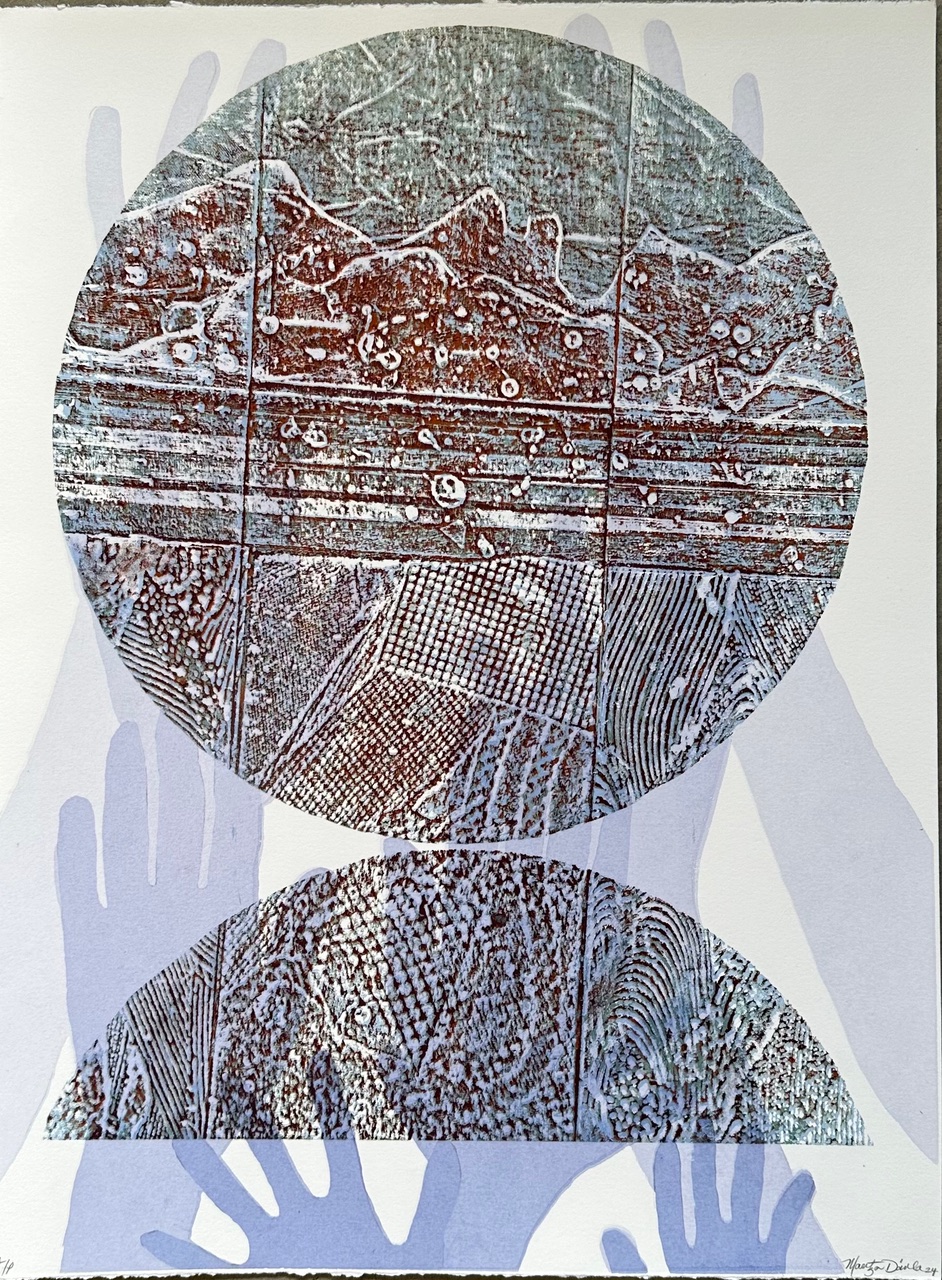

Atracciones Eternas (Eternity Attractions)

Screenprint

20″ x 22″

2024

B: I want to spend some time talking about the press and how you set up your home studio. I got to listen to you share about setting up Atabeira during Berel Lutsky’s INKubator session in Providence. So it’d be really great for our membership to hear about how you set up your home studio, how you opened it up to folks, and then what’s happened in the last few months and what’s happening now.

MD: As you know working in the university environment in the studio involves a lot of sacrifices, and one of them is the loss of privacy. You have to contend with having a student around who wants to ask questions. They usually come when you’re working because they’re curious about what you’re doing, you know. So you have to kind of navigate these interruptions and explaining or answering questions and then saying, “I need to do this now. I can answer those questions during my office hours or after class. Right now I need to do this”.

So my first home studio was in our first home in Memphis. We bought it because it had a small room next to the garage that I could use as my studio. We’re talking a space that is half the size of a one car garage. It’s small. We only had a one car garage, the studio was attached to it, and it was half of the one car garage. Though it did have beautiful light. It was the first place that I could call my own to work. I still had some etching inks and some stuff I did not want my children to be around, you know, so it gave me the opportunity for a secure space. It could go out a door, down a step, around back and through another door and I’m in my studio. So I could get my babies to take a nap in the house while I was working and I would come in to check. When they were older they would love to go in and help me out, bring a sandwich. So it was a godsend to me, but it gets small pretty fast.

My father-in-law gave me my first etching press, which was an Ettan 24” x 48”. Pretty decent size, but it pretty much took up the whole space. I had to walk around it because I had tables on one side, tables on the other side. When you have to do work in those circumstances, you don’t think about it. You just do it. I spent seven years in New York City working at a large table in my kitchen my apartment was a studio. If that’s what you have you don’t question it, just go with it because otherwise you do nothing, waiting for larger space.

I did just fine until we finally decided to fix the garage and put in sliding doors on one end. Acclimatize the garage so you could work. It’s not usually acclimatized. We’re talking a house built in the 50’s so the garage was bare bones. So we did that, and that was amazing. For one thing I can have my garage, my printing area, and then in the smaller space, my clean area, and my library. Oh, I was in heaven!

I started doing screenprinting and book binding. I did the paper at the college because that is a different set of needs. I was really happy. Until I was about to retire, or they decided to close down the college. And then I realized, if I want to get to do many of the things that I want to do, including teaching, I have to make the studio larger.

The studio footprint was very important in creating opportunities to myself and others. After the addition to the studio I started inviting a selected group of artists to my studio in 2022. At that time only a few artists and students came to the studio to use the facilities. I was on my way to invite more artists when the fire incident happened.

That was part of my presentation in Providence, is how I move on from a one person studio to a studio that I could accommodate people and different types of disciplines.Not too many, but just enough, or at least, if somebody wanted to come and do some work. Because there’s not public studios in Memphis. There is the university. So either you build something on your own, or you don’t do prints. Period. So I say, well, okay, this is it. I was ecstatic. I need to show you a big photograph of before and after. It was tremendous, and I’m so happy that I documented all of that. The whole process of building and then the final product.

And then this happens…

I made my presentation in March, and on April 23rd my studio burned down. The addition to the studio was no more than two years old. I was organizing all of it before I got to bring people into the space, because even when you have an addition you pretty much stop working because you have to move everything. Then, when the fire happened we had to start reorganizing again.

Remains of Atabeira Press after the April 23rd, 2024 fire.

B: Wow! So you had it just long enough to fall in love with the new space, and then it was gone.

MD: I had an interview, and people came for a local magazine and took photographs of this space, and they took photographs of my sketchbooks, because that is something that I adore, is to document and research in my sketchbooks.

It’s something that I’ve done for a long time, and something that I have developed a lot and care for. It’s something that I tried to teach my students. I’m a great believer that students who hate to have a sketchbook don’t know how to use a sketchbook. Once they go to the process I give them a map with the many ways that you can use this, as a diary, a sketchbook. You can see, if you follow all of these suggestions, you learn how to use a sketchbook. You have something that you will treasure because it has so much in it, and you can get a lot from it.

I had sketchbooks since my college years at University Puerto Rico, and then I started to use them when I started teaching in the college because all of my students had one. They became this space where I can document the work from beginning to finish. I have the space for it. I can put in the samples. I can show look, this is my process. This is the documentation of everything. You need this for key stories, documentation, and to go back and reflect and learn from it, all of those reasons.

So the fire happens on April 23rd. It was, thanks to one of my neighbors who saw the flames and the smoke. And they’re popping off the windows because there’s nothing like hearing a roaring file, and these explosions, and you know those are the windows. It was really something, and the house is so close. I went out with a hose and decided, I’m gonna spray the roof, which was caved in by then.

This happened at night. This was around 10:30 in the evening. When I opened the door I realized half the roof was gone. So I started wetting the roof, thinking if I wet the roof maybe the flames will not jump into the house because we were so close.

Then the fire department, in a nanosecond, we’re talking no more than 15 min, 10 min, let’s say, and they were there. What I can tell you is the care I received at that moment is something I have never experienced before. That fireman took my arm and told me, “We are here. We have you. You can let go. You can let go of the hose. We’re here. You need to go into the house”.

I tear up every time, because I was holding that host like my life was depending on it. I think I truly believe that I could salvage something. He just kept telling me it’s okay. You can let go. We’re here, go inside. When I came inside the paramedics came in to check me out. The whole thing lasted until 2 in the morning because they have to be sure there was nothing that would ignite.

You can imagine between the fire and the amount of water it took to take it down. It was a two car garage, because at that moment it was even a little bit larger than a two car garage, all the way to the back I think, it was a little longer than a regular garage these days. It was really an experience, now every time I heard about a fire all I can think of is my heart goes to anyone that goes through it, because it is really traumatic. But the first thing my husband told me is we’re going to rebuild and I told him, yes, we are going to rebuild.

My 1st thought when I get up in the morning is I need to make a list. I need to document everything visually. I need to see what is salvageable. You can not go in, they said. I don’t care, I need to check. I need to be sure that if there’s something that can be salvaged, I’m gonna do it.

That morning my daughter was here. My son was here. My artist friends. Closest friends were here. My neighbors were here. Some friends were here, and we started moving books and prints out the drawer. There were some that were shut down, especially the wooden ones, that we’d have to pry open. Then to realize how much can be salvaged, how much was just wet, how much was smoke on the edges. One thing that I’ve realized is how much glassine can protect any works on paper. Because when I open up the first thing that I saw was glassine that was absolutely like ebony and when I lifted it off the paper underneath was pristine.

Atabeira Press following the fire on April 23, 2024.

B: Wow!

MD:We know glassine, don’t we? We know that it protects from dust and dirt, and all of this stuff. Little did you know it also protects from smoke. It was truly amazing. Another thing that I realized is that metal flat files have a tendency for the water to seep in very easily. Not so much the wooden ones. Maybe because they’re tightly constructed. For whatever reason, you can see there’s smoke going in, but not so much water.

So that very same day, one friend of mine decided to make lines from tree to tree, because I have several trees in my backyard, get clothespins and start hanging everything wet. So we start pulling all of the prints, getting all the glassine out. We marveled about the only smoked areas were where the glassine was not touching. We started hanging them up and we hung prints for a couple days until it started raining, and then we started hanging inside the house.

One thing that I realized is how dangerous the smoke is. By the third day I have to run to the doctor. My lungs were damaged by the smoke because from the very first night going in and out and bringing stuff with that strong smell of smoke, my lung capacity had gone down considerably. I have to run to my asthma, doctor, because I do have asthma. The doctor told me your lungs are in such bad shape we need to do something right away. So they did that, and now, my lungs are much better, they have recovered, but it’s something to be mindful of in a situation like this. With the choices that you have, even choices to bring something that smells like smoke inside another area contaminates the area and therefore you can ingest all of that. So the first thing we did was to get lots of air purifiers. Lots of charcoal bags. Anything that smelled and was dry outside, bring it into the house and get it into a sealed plastic container with charcoal bags. Use a lot of baking soda and try to clean it up as much as possible. Let everything air outside before bringing it in. We went through this process of learning what works and doesn’t work.

The insurance people brought somebody to take down the building. The only thing that is left from the building is the cement flooring, that’s all that’s left. Equipment is all gone. You get this idea like, it looks okay, maybe salvageable. But then you have to think it was an electric fire. There’s heat and there’s water. If you try to work with a piece of equipment that had gone through that you risk yourself or having another file, because you don’t know how the heat and everything has affected the inside. So I finally decided for the sake of safety I had to get rid of my exposure units. My press melted, it was a phenolic press so the press bed melted completely.

B: SGCI was happy to share your GoFundMe to rebuild Atabeira Press. I’ve seen a number of print friends have provided help. Can you share how the crowdfunding has helped and how the rebuild process is progressing?

MD: The rebuilding of the studio is in process. The studio part starts in September but many books and art materials have already been purchased. The GoFundMe has been used to start getting materials to work with in my current workspace in one of the bedrooms in my house. I decided at first to get materials to clean my prints, artist books, books, and tools I managed to recover. I created several carts in different online businesses and started to buy depending on what was needed at the moment. So far I have gotten many books, and materials for bookbinding. The other carts will be purchased when I get the studio space.

Other materials like windows, doors, heating and cooling system, have been purchased at a discount or second hand to help with the cost of rebuilding the studio. Having a contractor I could trust and willing to work with me to lower the price of building was very important to me.

Framing out the new Atabeira Press studio. Begun September, 2024.

Homenaje al corazon humano (Homage to the human heart)

Collagraph, reduction woodcut

30″ x 11″, open to 71″ wide

2024 (work in progress)

Walk through of the framed in Atabeira Press studio, while roofers work overhead.

Roofing Atabeira!