Interview

Cameron Gray: Into the Wild

“Into the Wild” is a regular interview with early career print artists. Interviews will highlight the varied paths the subjects are taking to strike an accord between life and their artistic practice. Expect a balance of approaches, from those hopping the residency circuit, to those teaching part-time or who snagged the elusive tenure-track gig right out of the gate, or those working a desk job or waiting tables to afford access to a community print shop or maker space. In short, there’s many ways to “make it” and we want to share them all!

Have an idea for a person to interview? Please submit suggestions to the Interviews section of the Submissions portal below.

Cameron Gray, MFA

Cameron Gray is a Birmingham-born artist whose work focuses on Blackness in America. He uses his work to help him decipher his own understanding of self. He believes that Blackness isa universal force. He tries to reveal a small part of its glory through every work he creates. Through his artistic and social practice, he hopes to be a reminder to people of how we got here, with the intention to spark inspiration in Black Futures. Grounded in multimedia practice and employing a community-based focus, Gray’s artwork seeks to raise social consciousness by uniting thinking and making. His current body of work considers basketball as a cultural phenomenon and an expression of lyricism, beauty, and joy. In 2020, Gray founded the Buxton Initiative, an organization that centers Blackness in the realms of art, music, literature, and film. In 2021, he was the recipient of an Iowa American Rescue Plan grant and an Iowa Arts and Culture Resilience Grant. Using these awards, Gray conceived and received permission to install a permanent sculpture in a local Ames, Iowa park. This sculpture, “Black’d Out Books,” functions not only as an artwork but as a Little Free Library featuring books by Black authors, a first in the city’s history.

Artist Statement:

Through my art and my nonprofit work, my goal has always been to uplift and highlight the Black experience and beauty of our humanity. Constantly bombarded with negative representations of who we are and we are defined by these portrayals. With every work and program, I strive to remind Black people that we are the only ones who can define who we are. I want to provide my Black audiences with work/ programming that illustrates our beauty and humanity that the world seems to forget. Remember who you are.

Cameron Gray

The Interview

Blake Sanders: You began your academic journey at Auburn, then worked with Drive By Press at Oklahoma University before becoming a Crew Member and Press Assistant at Evil Prints in St. Louis. How did those experiences with a road-based operation and in a commercial & educational studio prepare you for the next step?

Cameron Gray: I knew Joseph because he used to work at Auburn as well. He was the person I fell in love with printmaking with, so I call him my print dad. He’s the one who brought me into the fold and I wouldn’t have the life I have now without meeting him. One day I was going to the painting studio and Joseph had his prints out and I was thinking, “what is this?” I didn’t know what medium it was. I was still a baby in art and didn’t start my art career till I was 18, so I just didn’t know. Joseph explained what print was and I signed up for a class literally the same day. And the rest is history, so they say.

I worked with him, so I got a scholarship to go to a workshop with him [Drive By Press] in Oklahoma. I didn’t go on the road with him, but I got to experience what it was like to be in a print community. At Auburn you’re a student and you work with a professor, but at that workshop I was being indoctrinated to a whole world, outside of the classroom, where we’d all work together. The routine was after we get done working for the day, we’d go hang out, enjoy ourselves, crack some jokes and then wake up early and get back into the studio. It was a beautiful introduction to the print community.

When I started working at Evil I got thrown into the real real of what the community is. I met my lifetime friends because of being at Evil, printing for Huck. The best way I can describe working there was–school was the training wheels. When I got there, it was, “Okay, now you’re on the ship, you’re on the crew, let’s steer this boat to hopefully some type of success”. That’s where I got my sea legs, learning how to right and truly print well and efficiently, and being introduced to business aspects of an art career like how grants work and how you work a job and then go to the press to work on your own stuff every day without feeling burnt out constantly.

My friends helped with that, too, because the crew members there were always in the shop. You’d get off work at seven and ask what they’re up to and they come help you print or vice versa. Quickly the attitude was I gotta go, too because I like hanging out with them so the shop becomes where we always go and have fun while we work. You never want to miss a moment at the shop, so you end up going there even when you didn’t even have to work on anything just to go see your friends and hang out. It probably didn’t help that there was a bar right next door! That time is one of my finest memories of my whole life, those three years, one of the best things that’s ever happened to me for sure.

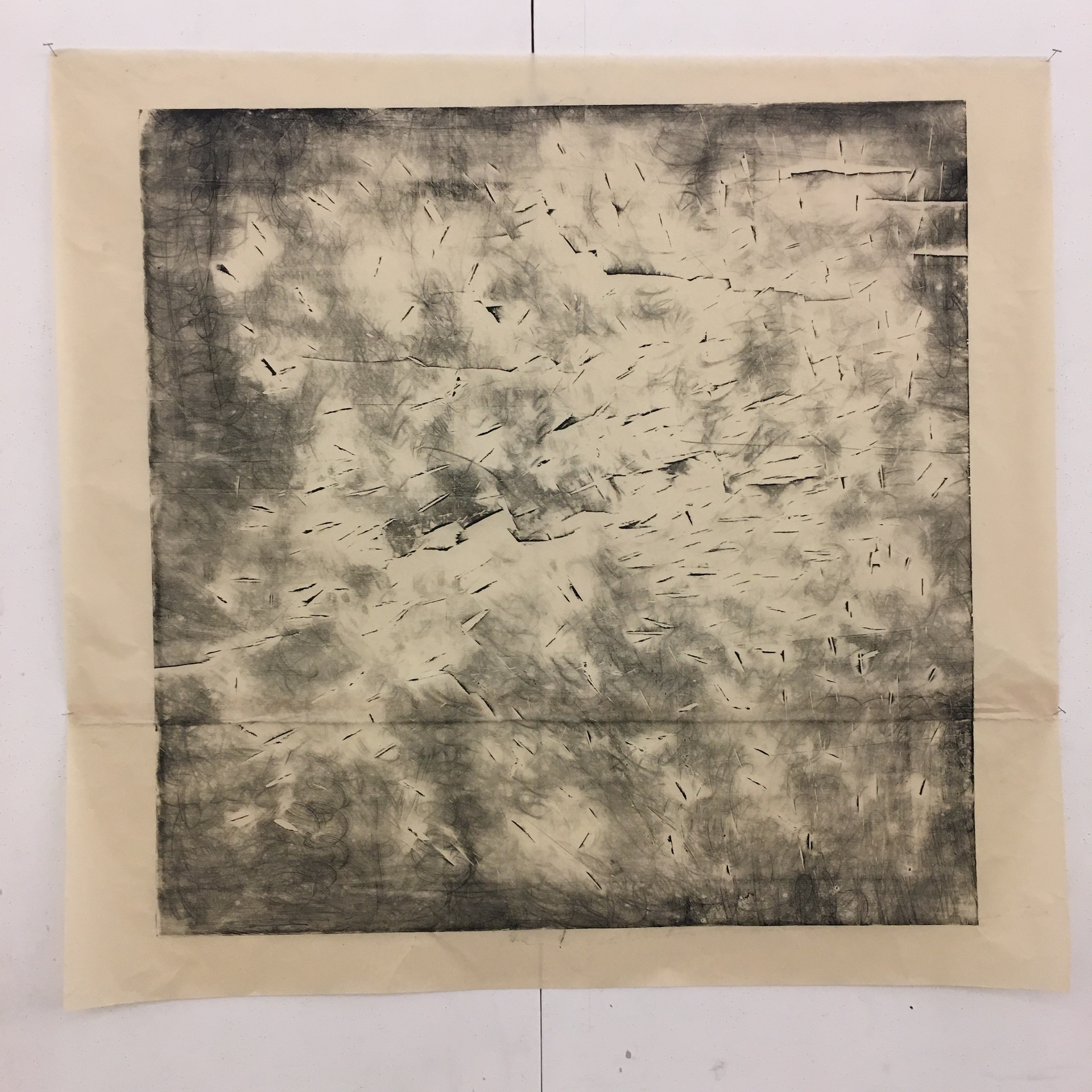

400 Cuts: Hatchet

Hand burnished wood relief print, 48″ x 48″, 2019

B: I’m curious how you chose to move from Evil. What was the impetus for you to then move on to grad school?

CG: It was financial more than anything. I was getting a scholarship to go. It also allowed me that space to understand what it meant to be working strictly as an artist. strictly, no other job, no other thing. Working on my work only. Teaching was a part of course, but I realized that the grad life seems more my speed. I’ve done the printing, I understand the technical aspects of the medium, now how can I push technical aspects of print beyond what I’d been doing before? How can I push that further with the resources that come with grad? I had an income [from teaching assistantship] so I don’t have to worry about going to another job. I was able to focus on being the CEO, carving out what I want to talk about as an artist, rather than helping another person reach their plateau. I was ready for my time in the sun, where I could figure out what to talk about and how to make the medium work for me.

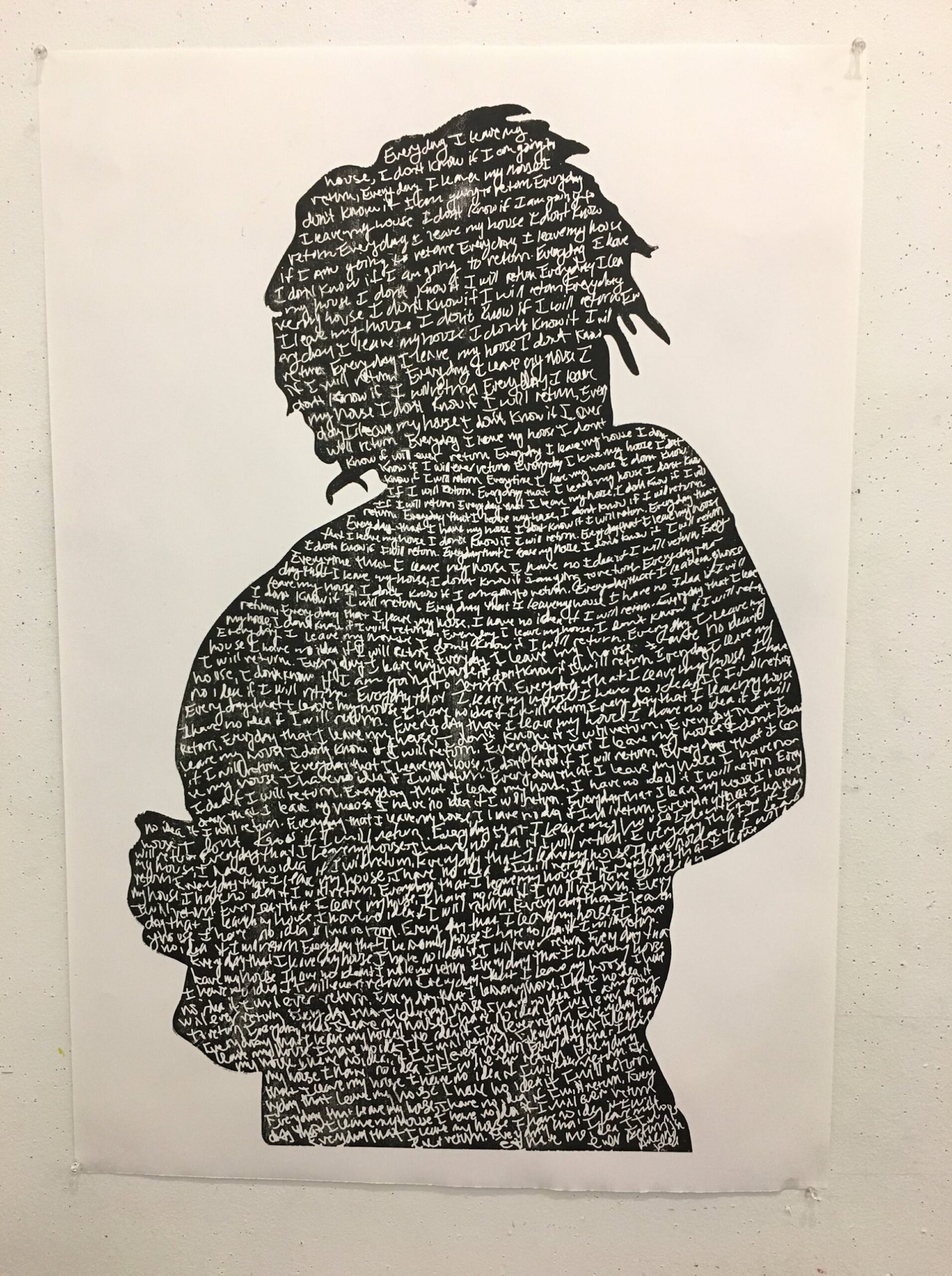

Black Confession II

Wood relief print, 25″ x 36″, 2019

B: How did you decide on Iowa State? What was that transition like moving from St. Louis–and before that Birmingham–to Ames, Iowa, which is a totally different animal?

G: Oh no, completely. I think that was the weirdest aspect for me. I got recruited by April Katz while I was at [SGCI Conference] Atlanta in 2017. She reached out to me by email after, which was kind of shocking to me, and said hey, if you want to come visit, you can. I thought sure, why not? I’ll go check out Ames. I had no idea where it was. Low key, I didn’t know where Iowa was in relation to Missouri. I had never been there before so it was a different thing.

I was telling my cousins about this trip and they were like, man make sure you stay safe because there’s not many Black people out there. That’s always in the back of my mind, coming up from the South, my pops always told me when you go to certain places make sure you’re safe. The first GPS was coming out around the time I started driving and sometimes the satellites weren’t that good so sometimes they would tell you to go somewhere but then it’s a dirt road or something like that. So Dad always told me whenever you’re on that kind of path just stay on the main road and it’ll direct you another way to get to where you’re going. Never go off those main roads. So that’s always in the back of my head. To this day, when I’m driving somewhere I’m staying on the main roads. I’m not trying to bother anybody on a gravel drive or be a surprise on this property by accident. That can end up tragically, not to get to somber!

Anyway, going to Ames there was a little–there was a lot–of nerves. I didn’t know anybody. I visited and it seemed like everyone wanted me to be a part of the program. They showed me around the school and it was a really beautiful trip. The thing that bothered me a little bit while I was there was the lack of diversity. I had never been in a place like that before coming from St. Louis and Birmingham, very beautiful Black cities. I couldn’t really find my way to be comfortable.

Thankfully, I met one of the Black faculty members, Brenda Jones who came to talk to me on the last day of my visit. We had coffee and the place that we were in, we’re the only two Black people there. I kept asking her how? How have you lasted this long? She said, “Well because they need me here”. She kept telling me how Iowa State needed a student like myself to to bring more awareness to the school’s microaggressions, and to understand the plight of what it means to be Black in America.

After that conversation I understood the importance of being a Black artist in a predominantly white, somewhat hostile space. It really convinced me that I could get some really good work done there through helping the community out and giving Black people who were already there opportunities to see themselves represented to some degree. If it wasn’t for Brenda Jones, I probably wouldn’t have gone to Iowa State. I’m very proud that I met her and she had that conversation with me. It brought a lot of things into perspective.

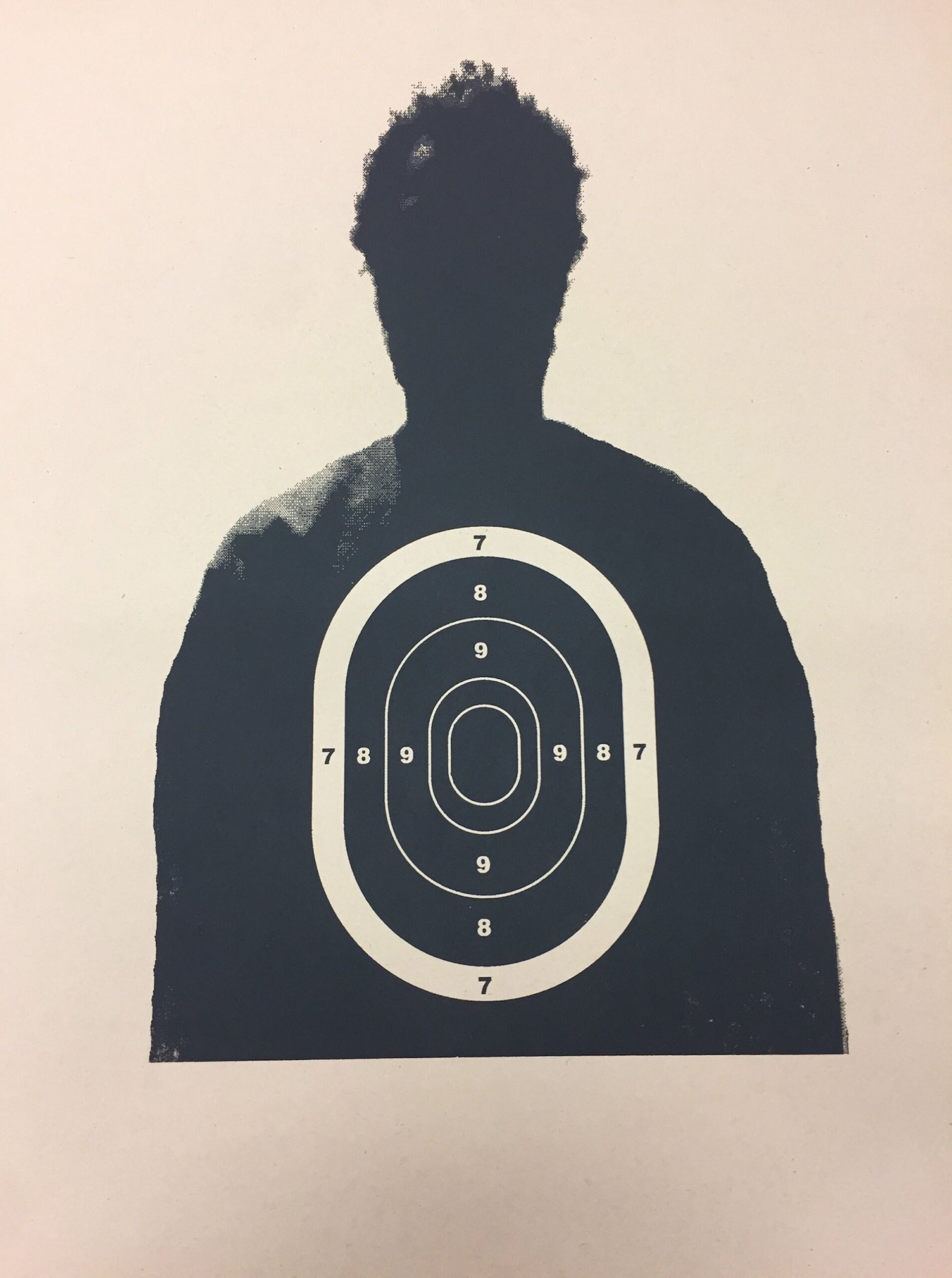

Target Practice

Screenprint, 20″x 30″, 2018

B: That’s excellent. You know, I am a white guy from Iowa. My family’s been in the state for at least seven or eight generations. I know that assimilation is the name of the game. So I was curious about your experience. I told you after the panel you were on in Madison that I was really glad that you were still in Ames, because like Brenda said, it’s important for representation sake and definitely showing the predominantly white folks there a different perspective, and how their expectation of assimilation isn’t productive, healthy or helpful.

CG: Totally. No, and somewhat combative to some degree. That’s something I’ve been focused on the past couple years, to stop focusing on trying to stimulate or even trying to get them to understand. We’re starting to have a growing Black community here now which is amazing and a lot of Black establishments have been opening up in downtown Ames, which is very encouraging for me because coming in 2017, there were no places that look like me or ran by people that look like me or having bartenders that look like me. Now there’s two places that feel like I’m in Birmingham or Atlanta or St. Louis. They’re run by Black people so that’s something that encourages me to stay because I want to foster that community even more. I’ve been having a lot of connections with these two establishments, trying to build something even bigger so that we can empower the people that are here. We’re thinking about how we can maintain this community, but also how we can make it grow. How can we start to bring even more people to Ames, Iowa? With my nonprofit there’s a lot of initiatives that I’m doing to bring awareness to Black artists that are not even in the region, to bring them to Ames, of all places. So that Black folks hopefully years down the line people can see Ames as a hub where you can see the latest Black artist being shown in a space that’s run by me or run by some other Black organization or a Black space.

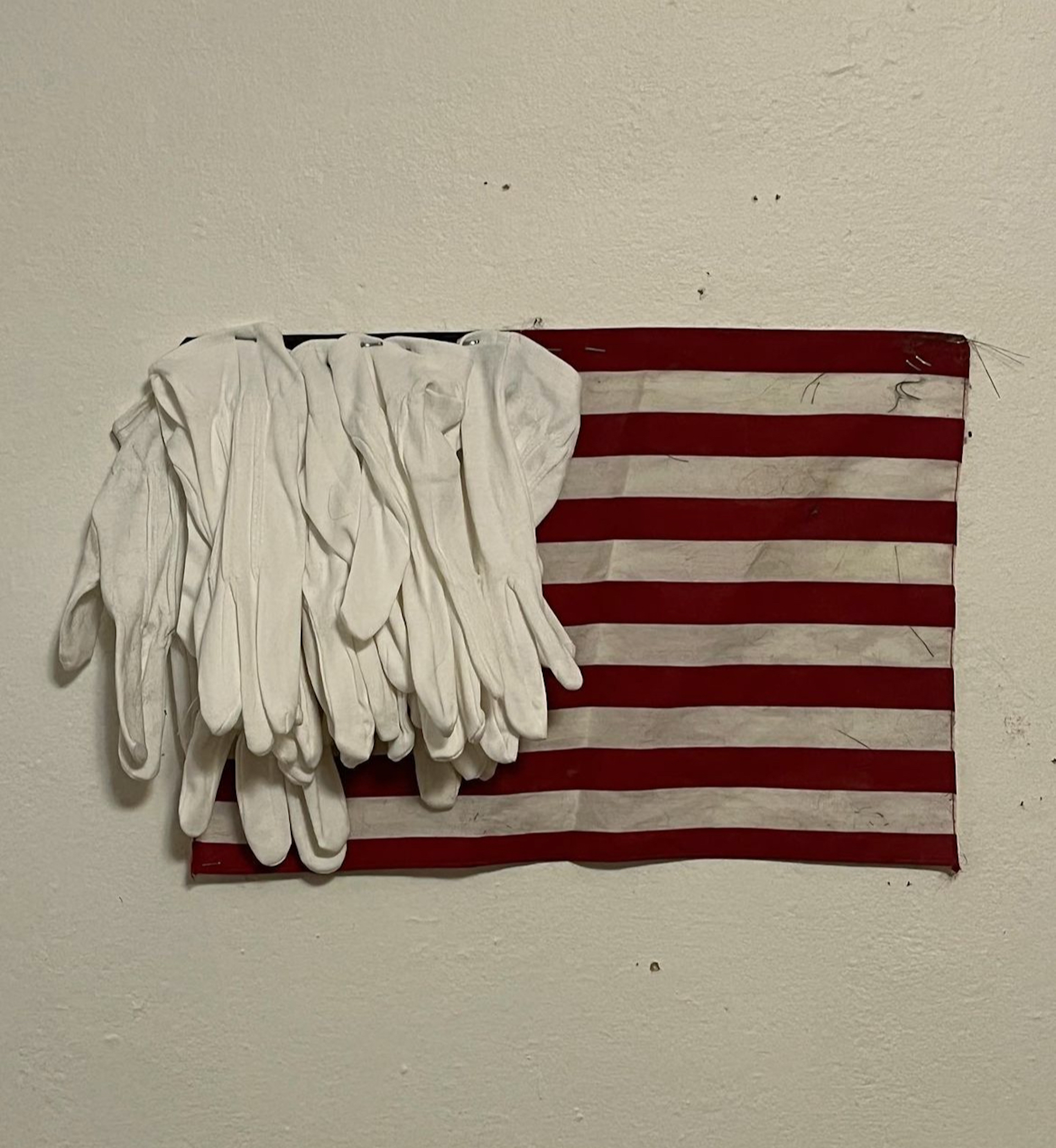

They Don’t Want to See These Hands

American flag and white cloth gloves, 10″ x 16″, 2022

B: That’s great. I definitely want to come back and talk about the Buxton Initiative here in a little bit. For now, part of the goal of the “Into the Wild” feature is to highlight the different paths printmakers take earlier in their careers to find professional satisfaction. Often that means taking jobs outside the field to find economic stability necessary to maintain your art career. Can you share about what you’re doing, outside the Buxton Initiative, to earn a living and how that day to day labor accommodates or supports your art career?

CG: I’ve been quite blessed. I’m not doing as much of the side business, printing t-shirts or selling photographs and selling posters and whatnot. When I do, all that stuff gets funneled back into the budget. I’ve come to a point where my whole practice really is just a big bubble. Every project supports each other. Whatever funds I don’t get from printing, they come out of my pocket because I gotta keep these programs running.

I finished graduate school in 2020, probably the worst year to ever graduate. Most people know the grad. school routine. You work for three years then you get to have this beautiful show that you invite all your family and friends to come see. You get to present all the stuff you’ve been working on, and here’s your heart essentially and you’re excited to give it to them. But for me, that moment was kind of dashed. I was told no one can come to this show. You’re gonna have to photograph it, send all the things to your faculty, and no one could ever see this work that you work so hard for was kind of heartbreaking to be honest.

That was the first couple of months of lockdown and thankfully I had like enough money saved up for a little bit to figure out what the next steps are. We were getting those stimulus checks, too, so it gave me the opportunity to think, okay, this is gonna run out. They’re not gonna keep giving these checks all the time, so what is the next step for me to do as a creative?

So I had the facilities in the house I was living in to start printing t-shirts, and I started doing a bunch of sweatshirts for people. I started to push that aspect of my career. I was also doing a lot of grant writing, trying to supplement some income. Whatever I didn’t make in t-shirts I would make up for in grants. I was also selling photographs to support projects I was working on as well. The Buxton Initiative began around that time, too. Someone approached me and said we know you’re trying to start some Black programming. We want that for our organization. What can we do to support you? So then I was getting funds from there as well.

A combination of all of these things became this creative synergy. There is no end to my practice. Everything I do with the Buxton Initiative is tied into my art practice because it’s so close to me. I’m only doing programs that have some type of emotional connection to who I am as an individual. And so I love that there is no end or beginning to it. It makes me feel like no matter what I’m doing on a particular day, it feeds into my other art practice. I’m just really grateful that there’s no division now, it’s all me at the end of the day.

B: You described this synergy in your work with this bubble analogy, which I think is really beautiful. The roundness relates to the cyclical nature of an art career, while the support and tension necessary to keep the bubble together is the same sort of delicate balance we’re all trying to achieve.

CG: When you start to see it is all one thing it makes it easier. I used to get down on myself when I was doing something like printing t-shirts to make ends meet when what I wanted was to be in the studio working. It took me realizing that I liked the shirts, too, and people liked them and that made it important. If you put your personality in the thing that is commercial or design for clients that’s how you can then find that through line so that a project that when you have been dreading you can remember this is a part of me, too that I’m really excited and happy for.

I find a way that makes me excited to get it done. Try to choose jobs where you can feel creative within the parameters of the assignment. Sometimes you need another outlet, like doing labor for people, or inviting people to do shows with you to find funds that way, or collaborations with other artists as a revenue stream.

There’s so many different ways to find money. Sometimes it’ll take you a day to sit down and map out your plan to figure out how to find those funds. Always try to do an inventory of all your resources first. Can I sell prints for a little bit cheaper? I have all these prints that I made a couple years ago. I can let those things go because I’m starting to move towards different work. We make a lot of prints and so you really don’t need twenty of them, right?

If you had to get another job too, that works, but I would always say start with what you have and make parting with your work part of your practice. Once people understand that that is something you do, that practice becomes synonymous with you and you start to build an audience. Hopefully things start to grow and build so that you won’t have to go to that 9 to 5 drive that you were working before. You can just strictly do what you’re doing right now because you’ve established that fan base. It takes time, so be patient with yourself. You’re gonna have some frustrating months where you’re barely making it. If you stick to your guns you’ll find a way I promise you. Every time that I’ve always thought that I wouldn’t make it there was something that came my way. Never falter in your endeavors. It’ll be a tough road but keep having faith in yourself, keep doing the work and it will all work out. Promise.

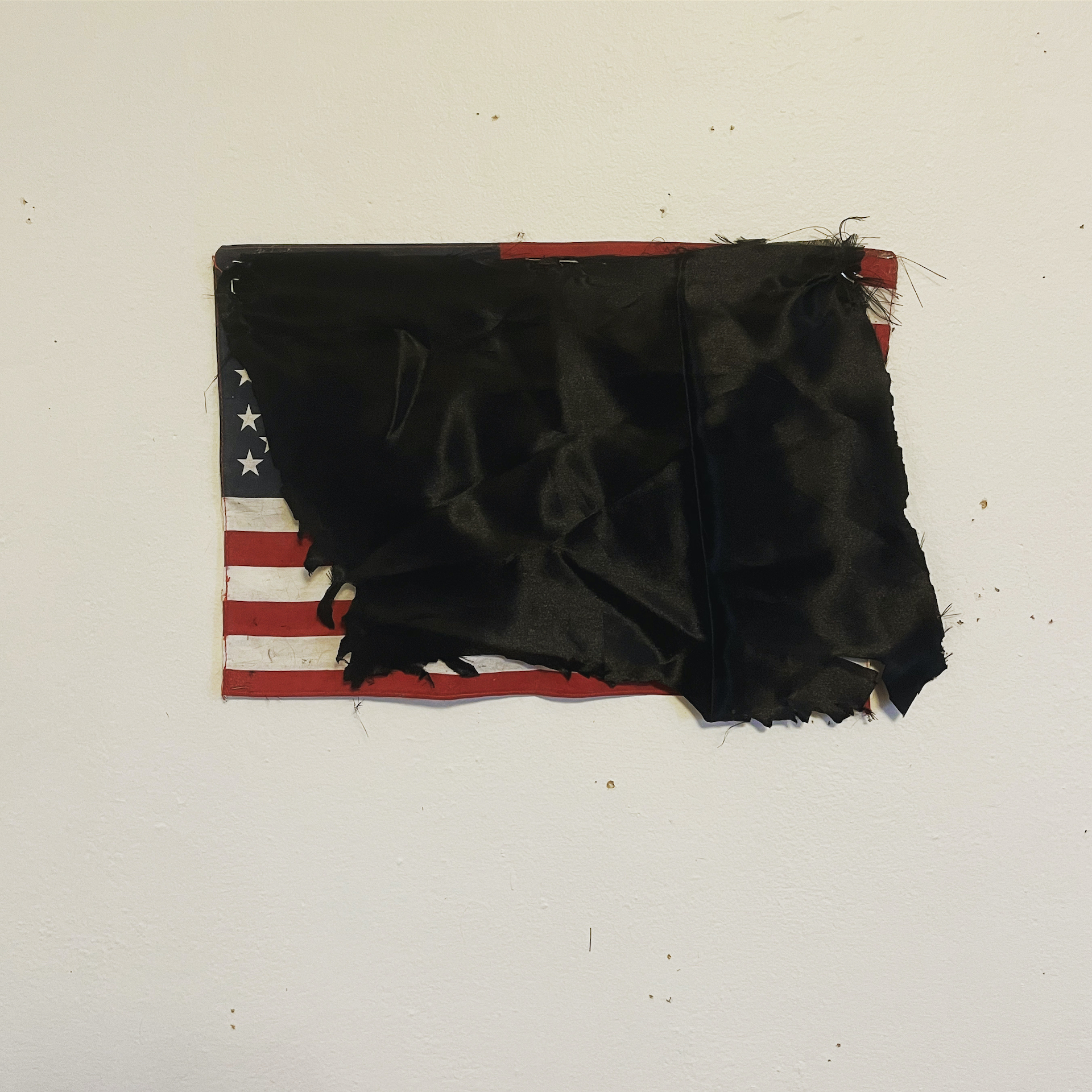

Eclipsed

American flag and black satin, 10″ x 16″, 2022

B: Well said. A lot of the work that you are making is a departure from traditional printmaking. How do you square this sort of multimedia experience of your practice with that background in edition-centered printmaking?

CG: That’s the hard part. I want to be in the studio and I miss it so much. I miss that community, of getting to the print studio, staying there for hours on end, maybe having a beer right next to me while I’m carving, and being in that space around other printmakers. That’s the impetus of all this, right? That’s something that I truly miss and I wish I could get back into doing.

The practice I have now is still very involved in the print field. I’ve always loved monoprints. If you work for a person you have to edition for constantly, your love of editioning kinda goes out the window. I don’t see the need for it. If I can get a couple good ones that’s good for me. It shows I understand the image, I understand what this is supposed to be, there doesn’t need to be 20 or 30 of these things. Plus, where I’m living, I need storage space!

What I love so much about what I’m doing currently is that it’s still influenced by the print medium. A lot of my performances are only happening once. They’re not a repeated action that people get to experience over and over. That makes it another monoprint, right? For my thesis show I did a body print of where I poured out charcoal and laid in it. When people walked through the studio, they could see the form of my body in that space. That’s another print. Just because things aren’t permanent doesn’t mean that they don’t fall in line with the foundation of what the printmaking process is.

Photography is a print process. I love being able to shoot my performances. Shooting my body is a really beautiful way to hold onto those printmaking roots. I’m working

on this project now where I make movie posters every month. I’ve been trying to figure out how to get that tactile quality of a screenprint–I want to screenprint these, but I don’t have a press of screenprint materials–so I’ve been trying to get that tactile nature at Kinkos, which has been fun.

I want to get some French Paper for screenprinting then run it through the machines at Kinkos

To get that tactility so it feels like a print even though it is a digital drawing. I want to give people that tactile experience of holding a hand-printed 19” x 25” movie poster.

Catching My Breath

Video installation and coal, 2022

B: Your work is focused on Blackness in America with visibility, achievement, and empowerment as priorities. How does the diversity of media and methodologies you employ reinforce that Black pride and beauty in your art?

CG: One thing I learned about myself is I love artists who find found objects and give them back life. There’s something really beautiful within the Black tradition, taking what is there and making something out of it. Being resourceful. Take chitlins, for example. My mom loves chitlins, and they’re a byproduct of taking every part of the pig and trying to make it taste good or make it useful. I think about my work in the tradition of that beautiful history. There’s beauty in linking to that Black tradition of creating beauty out of making do. It’s talking about Black plight, but also the beauty of what Black people can create.

I’m also talking about the beauty of Black joy and reminding myself of the beautiful moments I’ve had with my family. The last year was really tough, lot of loss. I realized how much my family means to me and how much they helped me just by being around them. Making me laugh, cracking jokes, playing cards, doing all these other things when I get to go home. My new work is all Black joy and Black love and trying to make sure that I am maintaining some of these good moments through recording them. When I go home I’ll leave my phone on the counter and just see what comes up, what got said around my phone at that time. When I go back and listen there are always funny conversations and anecdotes. I’m making sure to capture these moments so that as my family gets older–we’ve already lost a couple people–so I’m certain I’m preserving enough information, enough media so that when their time comes I have their stories and anecdotes logged so you’re still able to hear them in their brilliance and their beauty.

So when I have kids I can say, I know you didn’t get to meet your auntie, but like this is what she sounded like, this is what her vibrato was and like what she sounded like when she sang.

I’m maintaining that ecosystem of my family whether they’re here or gone so future generations can understand who they were as human beings through their stories and their voices.

B: I see a print connection there, too. You’re recording personal history, creating a matrix. That’s printmaking, repurposing history to communicate with an audience.

CG: I see it as an illuminated manuscript of literally family records. That’s my goal is to actually press all of these audio pieces into records then have them live in my parents home next to a record player so that if you want to hear my grandmother just put on that record and you can hear tell a story. The records will maintain those beautiful connections. No one was doing this for me when my grandmother was talking about her mama. I thought it’d be amazing just to have the person talk to you about the thing rather than having to do research about it later. Let’s start recording these stories now so that by the time that I’m 70 I have a whole library of voices of everyone talking about their experiences because it’s important. People need to know how our family came to be and what makes our family special.

B: That’s really beautiful. It’d be amazing if you could expand that process to scale so you could allow other people to build their histories through that recording method sort of like a Story Corps thing for the broader Black community in your area.

CG: I already told my mom this. I’ve been recording them since 2018. When I was writing my thesis I asked to record them so I could get an understanding of where I came from and how I created this work. Right away I realized, oh man there’s something here, right? Even though I’m doing this for my thesis, I need to continue recording these stories for myself. Last time I was home, I told my mom, when I finished this project I didn’t want to put it on display at a gallery or something. These are our stories and I want to keep them in the family. There’s something private and beautiful in the idea that only our family can listen to these records because it’s our story. This is something I made for our family to keep our lineage or our stories. You’ll probably see some of those stories within the work I’m making, but you’re not gonna hear my grandmother’s voice because that’s not meant for you. It’s meant for the family to hear and listen to and learn from.

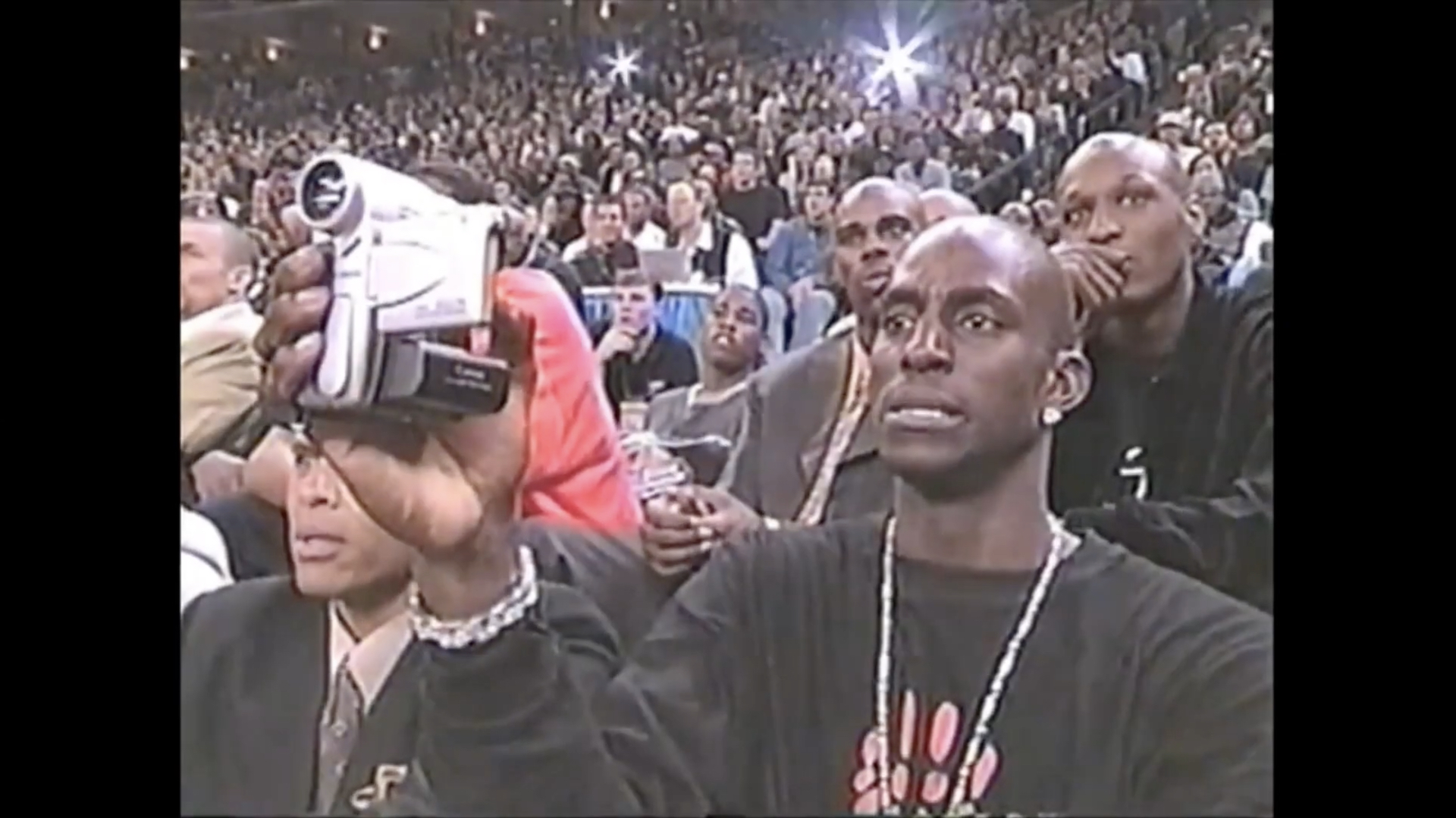

The Rumination of Black Joy

Video still, 5m 36s, 2023

B: Speaking about this personal library is a good way to transition back into talking about the Buxton Initiative and specifically the Black’d Out Books project, which is more of a public library.

CG: Yeah, 100%. A couple of years ago, I was dating somebody and I was telling them about a project I was working on where people could come pick up Black books. They’d ring my doorbell, tell me what kind of book they want, and I’d give them a recommendation for a Black book. She was like, well, why don’t you just do a Black free library? I said okay, you’re right. Sometimes the ideas of things sound so cool, and it’s always good to have people like that around who can poke holes in your somewhat crazy ideas to help you come up with a logical solution. Once it was a Black free library I realized it could be whatever I wanted it to be. I started with a design of your typical free little library with a wooden post and a box on top of it and then you just fill it with books. Then I thought, I’m an artist, I can make this into whatever I want, it doesn’t necessarily have to be this familiar thing. If I want to make this metal, I can. I started thinking about different shapes that were indicative of knowledge or holy spaces. I couldn’t help but think about an obelisk because it has African roots, but it’s a signifier for a holy place to some degree. I love that this would be a monument trying to channel the heavens to bring down that power into this particular place.

I always thought about a lot of these books as narratives left by authors who have passed away but the library creates a conduit through reading, where their stories are still flowing to you.

I love the notion of channeling the ancestors or channeling ancestral stories and bringing that to other Black folks and and vice versa because visitors are able to share their stories, too. As you’re taking the book, you can input a story that could be from an ancestor that impacted you that you want to share with another person. It creates a conversation with the ancestral plane and the artists and authors that are here today. This process of passing on stories is a very Black tradition. It’s like what I’m doing with my family right now passing stories on in a tangible community-based way so it has been the biggest project that I’m really excited about bringing to the public.

To date we’ve collected over a thousand books so it’s going to be incredible. The reason I continued collecting is because I hope once we get this first one up there can be more. Others can get involved because we know how to build it. Let’s get another one up somewhere now that we’ve shown people that it’s a proven concept. We can bring this to any city that we want to after that. My fabricator knows what he’s doing, there’s no question about it, so when’s the next one coming up? We’re gonna make some tweaks for this one and of course we’re going to make some tweaks for the ones that come after, but this allows us to be able to send the books to fill the libraries when they’re ready. For the past 3 years, but I have amassed the collection, now I’m prepared to fill another one up here then there, and when others contribute that exchange can continue. That’s what I’m looking for.

B: That cycle, and momentum. It sounds like it could become the most benevolent form of franchising!

CG: We’re hoping so. I have the idea of bringing these things to Birmingham, like I already know a location.I will do it in Birmingham for sure. The next place I would like to bring one is to St. Louis. Those are my top places that have really affected me in my life.To give back to those communities and those cities that have given so much to me and to help the same people who have inspired me to be the artist I am today would be a blessing.

Flying Abstraction

Video performance still, 17m 10s, 2023

B: Where do you see your work developing in the next few years? What does success look like for you?

CG: Honestly, I feel like I’m in it right now. Being able to do these projects that I’ve been thinking about for years like “We Go in the Dark”, has been cooking since the beginning of the Buxton Initiative, that was the basis of it. It’s a celebration of Black art ,music,television, film and every aspect of Black media. That one has been the most personal one.

Watching movies on a screen like this, in a chair like this, at home as a kid was always my safe space. I loved film so when things weren’t going right at school or something that was always a safe space where I could feel comfortable and it allowed me to get out of my head for a second and exist within the confines of the narrative. It was like a mini vacation, but I was upstairs in my room watching something. In that same vein it kind of goes back to what we were talking about before about blurring that line between my art practice and who I am as an individual. For “We Go in the Dark” I show movies for the community. Last week we watched like Bebe’s Kids, which was a pivotal movie for me. To give other kids that experience was a beautiful thing, and it was such an honor to be able to give that to them.

I know that I will never go off my path of leaning into my own intimacy–which is difficult for me to do sometimes–allowing people into myself because I’ve been hurt a lot. Allowing people to see me for who I am, take it or leave it. Showing myself and not being afraid to express myself in a very open, sincere way. Really leaning into joy because if you look at some of my past work it was a very antagonistic way of viewing the harm that has been inflicted on Black people. I really wanted to get away from that because I realized a lot of Black folks right now want connection and love and seeing that illustrated in programming, in education, in just having a good time.

We want to enjoy each other’s company and just love one another. I love that I’m finding what Black love feels like to me. I’m getting people to understand the beauty of that feeling when your grandmother hugs you. To really spend time with her waking up with the smell of coffee and oatmeal in the morning. How do I start to make work so I can track those moments and those things that bring me so much joy. A lot of that other work was me putting a wall in front of myself.

It’s easy to talk about anger because it doesn’t require much investigation to get to that spot. Allowing people, on the other hand, is scary. Figuring out how to do that though is a wonderful part of my life and work and I’m excited to bring people in. I also want to remind people to slow down a little bit and dive into those connections that you have because you don’t know how long they’re gonna last.

Her Throne

Photography, 2024

B: You’ve given us a lot of amazing insights today. What advice would you give current students as they’re continuing their journey and about to go Into the Wild? What do you wish you’d been told or prepared for?

CG: Just keep doing the work. I can’t tell you how many people that I thought were going to be incredible artists and they stopped doing the work because it got tough. You have to stay focused. You’re gonna have some hard times for sure. It’s not always gonna be easy to get back into the studio, especially when you’ve worked five to seven days out of the week already, but try to do something, even if it’s drawing for 30 minutes or doing research on a project you want to do. Small increments all build up to something bigger. When you don’t feel like you’re doing something on a daily basis working towards your own art career you still are because you’re building experience, you’re constantly thinking about your practice. Just because you’re not going into the studio and making something doesn’t mean you’re not doing the work in order to get to the work you want to create. Give yourself grace, it’s okay.

Something I wish someone would tell me was not everyone’s studio practice looks the same. Don’t let anyone shame you for the amount of work you’re doing or the way that you work. Whatever works for you works for you. Do you still make dope work? That’s the only thing that matters. Don’t worry about your friend who goes to the studio seven days a week. You don’t know what their circumstances are, what they’re going through or what they’ve been able to acquire to allow them to go to the studio all the time. You will get there. Just be patient with yourself. Give yourself grace. Rest, that’s important. Everything else will work itself out. Take care of yourself for sure.

B: Yeah, that’s all good advice. I think it took the pandemic for me to slow down a little bit.

CG: Oh, me too. You start going crazy, right? You start to wonder if you’re going in the right direction. Depression is real. Get to therapy. I want to say that. That’s maybe the real message. Therapy will help you. Emotionally, it helped me sort some things out and allowed the work to get better because it frees up your mind to actually get back to what you actually want to talk about and do. So yeah, get to therapy. We’ll just leave it there.

B: I sure thank you for your time today.

CG: No, of course. Thank you.