Articles

Artists’ Proof: An Essay by H Schenck

H Schenck (b. 1988, he/him) is an artist/educator/curator whose work speaks about belonging and uplifts marginalized perspectives. His practice is rooted in his experience as a disabled trans person and influenced by a transient, rural upbringing. Schenck integrates themes of identity and place by utilizing found and discarded materials, exploring art methodologies, and examining social concepts of value, meaning, and connection. He earned his BFA in Printmaking at Bradley University (2010) and his MFA in Intermedia at University of Texas Arlington (2013). Schenck is a Frogman’s (2009) alum, and specializes in the process of vitreography. He has taught and presented this technique, which uses glass as a matrix, at Ox-Bow School of Art (2023), University of Wisconsin Madison (2023), Dallas Arts Center (2012-2014), and Pilchuck Glass School (2013-2018). His work has been exhibited domestically and internationally at several institutions including, BWA Wrocław Galleries (Poland), 2nd Berlin Becher Triennial (Germany), The Modern Art Museum (Fort Worth), Urban Glass (NY), Traver Gallery (Seattle), MAC (Dallas), and other locations throughout the United States. Schenck has received funding from the Dallas Museum of Art, the MAC, Penland School of Crafts, Southern Graphics Council International, and the Kotteman Foundation. He was the co-creator of the social project Mud Campaign, which provided free arts education and funding for LGBTQ+ youth in Texas. He held memberships with BEEFHAUS (curator) , 500X Gallery (VP), and Comfort Station (Gallery Manager). Currently, he teaches at the Art Institute of Chicago and holds the titles of Instructional Specialist and Anti-racist Transformation Team Fellow at Columbia College Chicago.

H Schenck

Social Media: @h_marsh_schenck

Website: www.hschenck.com

Prologue

The exhibition Artists’ Proof presents the work of nine early career artists who each challenge traditional printmaking norms by applying print principles outside institutional boundaries. I met and worked with these artists in the printmaking studio at Columbia College Chicago. The print shop became a vital component of their practice, blending printmaking techniques with painting, digital illustration, bookmaking, wheat pasting, tattooing, and conceptually based installations.

I established three clear objectives for this show: promote artists with marginalized identities, disrupt the canon of traditional print exhibitions, and optimize Southern Graphics Council International’s institutional authority to legitimize and publish a selection of emerging artists. This exhibition proposes an interdisciplinary future for the medium exemplified by individuals who hold identities underrepresented in the field while connecting the artists in the exhibition to institutional history, resources, and opportunities SGCI holds.

I am inspired and humbled by how clearly and boldly this group of artists speaks their truth in their work. Finding an authentic voice is challenging for any artist. For emerging artists, it can feel nearly impossible to articulate when the experience you seek to express is not reflected to you by the art institutions, educational materials, and educators responsible for facilitating growth. As a young queer artist, I had little to no exposure to other queer artists and zero access to trans artists or their histories. Connecting with and learning from folx who hold various marginalized identities taught me the power of questioning traditional methodologies and the value of identifying connective tissue across media.

Post-graduation, these determined individuals have sought out resources, jury-rigged their bedrooms into studios, hustled wares to afford supplies, conceptualized their thinking to shift ideas about the matrix, and subverted the importance of an edition. These actions illustrate their tenacity, love for the process, and the reflexive innovation of an artistic practice lacking institutional support and funding. Within the context of a traditional printmaking education, proofs are often deemed inconsequential artifacts of the editioning process, yet, for the artists exhibited, the title Artists’ Proof emphasizes the importance of play and exploration inherent in printmaking.

To view the Artist’s Proof exhibition in its entirety please click here

Can a repeatable matrix be a wheatpasted proof for making a call to action?

Ziccy Delamarter’s (they/them) has a dynamic wheat pasting practice, inserting graphic lithograph proofs on newsprint into public space, which confronts passersby with messages reflective of political print history. Not only does their work challenge societal opinions on decay, rape culture, and the atrocities in Gaza, but it also elevates the proof as a powerful tool to be deployed. Delamarter’s prolific work reaches people more immediately and honestly than the distribution of a “formal” edition of prints ever could.

An ode to Gentileschi references the historical art canon piece, Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi. Similar to Gentileschi’s painting of the biblical story of the heroine Judith, challenging her rapist (Agostino Tassi) and reclaiming her power as a woman, Delamarter gives us a contemporary call steeped in queer reclamation. They flip the Frankenstein’s monster trope, presenting a self-made, self-reconstructed, partially nude figure proudly presenting the head of their assumed rapist. The figure looking directly at the viewer, aflame with confidence and relaxation listening to their favorite jams, challenges us to “Kill your local rapist!” This call to action seeks to hold sexual offenders accountable, unabashed by cultural norms that seek to silence victims. Delamarter prioritizes honest, accessible work that centers on the human experience, using historical imagery to emphasize and raise awareness of the generations of survivors of sexual assault.

Ziccy Delamarter, An Ode to Gentileschi, Wheatpasted Lithograph on Newsprint, print dimensions: 16” x 22”

Artists who actively engage with their communities, using printmaking to push their voice forward, untethered by classical exhibitions or institutions, exemplify the ethos of print’s origins. To call on the people.

Can a repeatable matrix be a method for immortalizing histories of marginalized peoples?

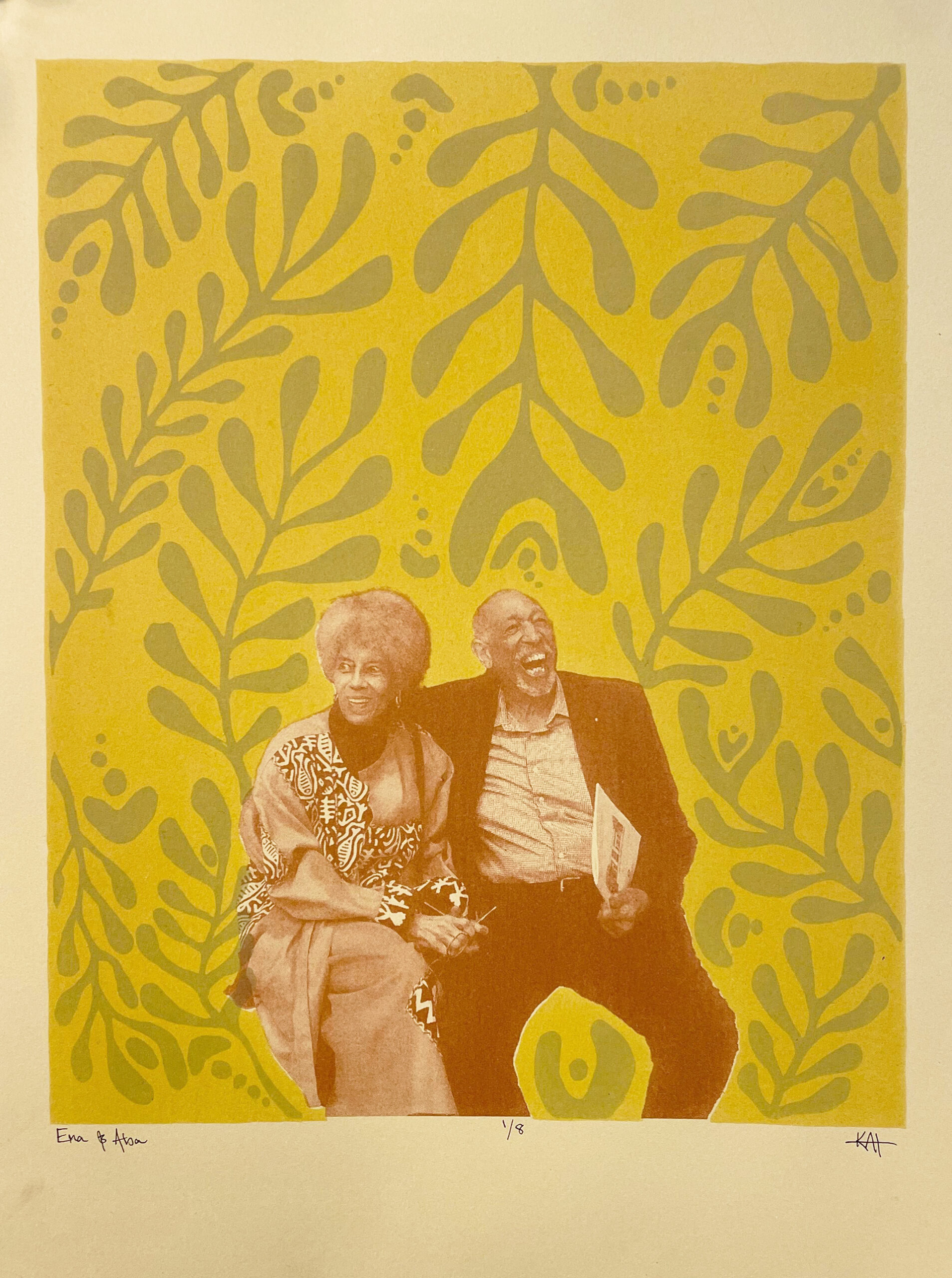

Kai Offett (she/her) reclaims printmaking’s authority and preservational longevity to generate archives of the people in her family, their traditions, and generational history. Within her practice, Offett acknowledges the gross cultural, financial, and educational gaps within the artistic disciplines, disproportionately impacting the folx of the global majority, and speaks about the negative impact of “paper genocide” suffered by generations of indigenous and black populations. Within the United States, the preservation of marginalized people’s familial history and heritage was not prioritized and intentionally erased, hence the term “paper genocide”. Generations of knowledge and culture have been lost due to enslavement and assimilation practices.

To push against these norms, both as a form of resistance and advocacy, Offett conceptually centers African symbols and words from Gauna, such as Sankofa, which means to “retrieve” or “return to and get.” By publishing editions of lithographic prints illustrating people from various generations in her family, she reaches through time, bringing her foremothers to the present as an archival lexicon of Black lineage. Offett relates and utilizes the practice of printing an edition to that of an archivist, denoting acts of care, attention, and recording.

Kai Offett, EMA & ABA, Lithograph, 11” x 15”

Thankfully, colleges and universities continue to improve diversity among faculty, but unfortunately, higher education is still dominated by curricula, dialog, and rubrics rooted in racial bias and white supremacy. As a marginalized emerging artist, repeatedly having to explain one’s culture to colleagues and professors can be destabilizing and unproductive. Every artist deserves the opportunity to have their work dissected by people with a baseline understanding of context. Kai Offet’s practice demonstrates not only her ability to provide educational frameworks in accessing her work but also raises the question of why academia expects artists like her to do so.

Can a repeatable matrix be a loom for weaving images?

Jensen Delius’ (she/they) practice, rooted in print, bookmaking, and papermaking, had to shift post-graduation due to a lack of press access. Delius began using a loom to create tapestry weavings. Continuing on with her methodology of centering their family history as a visual lexicon, the Home series consists of three blue placemats with image inlays depicting various family homes. Similarly to the repetitive nature of printing, her weavings illustrate the power of process and image-making.

Jensen Delius, Home, Cotton thread woven on a four-shaft loom with inlay and tapestry weaving, 18” x 12”

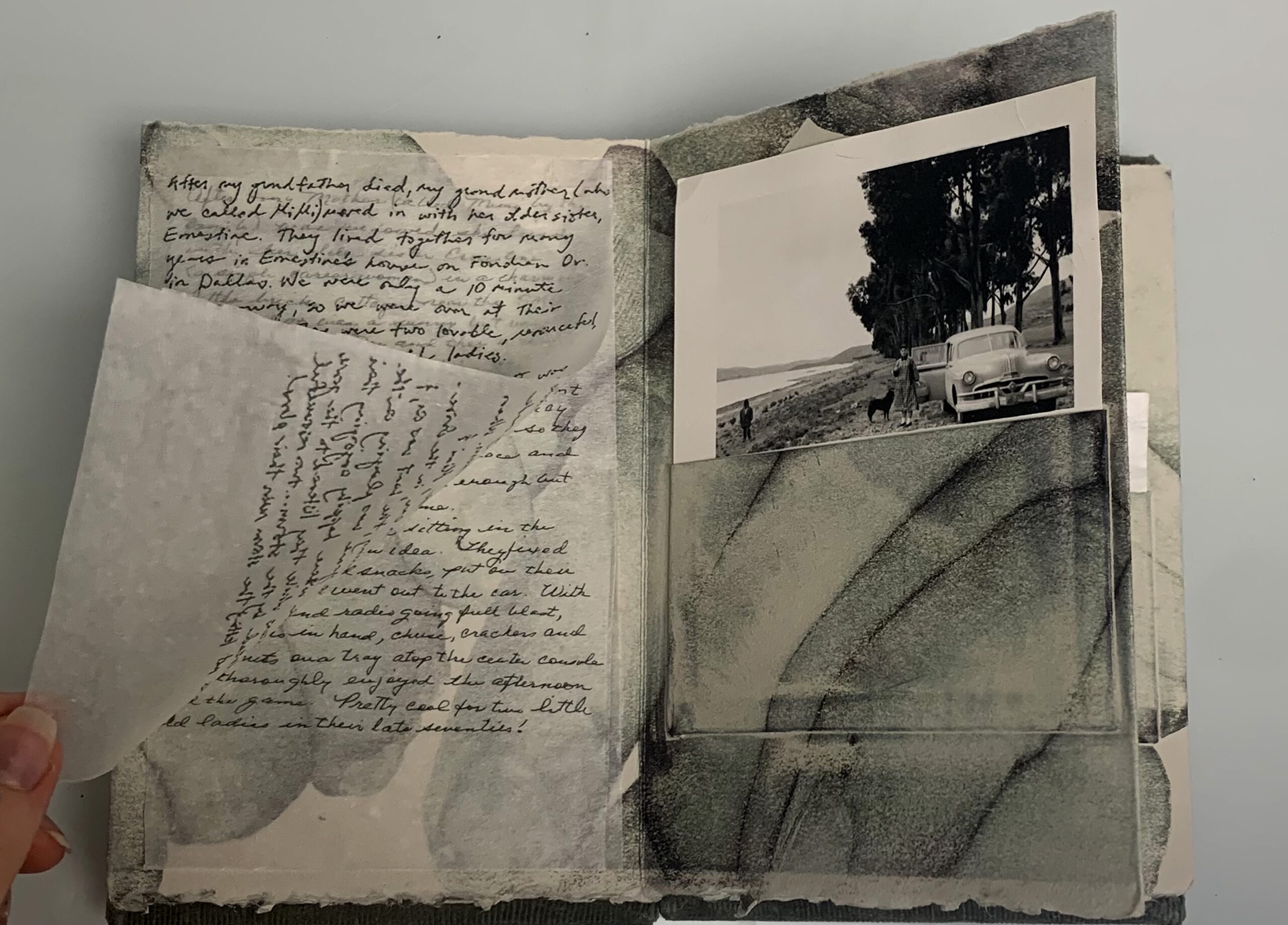

Delius’ artist book, Cotton Bowl from the Cadillac, consists of various print processes to archive and publish queer familial narratives. Upon first glance, the page layouts of lithographically printed handwritten text paired with personal photographs present an interactive story from three generational perspectives: the artist, her mother, and grandmother. Framed throughout the book by degraded images of all three women’s hands, concepts of generational inheritance, labor, and perspective emerge. Viewers are invited to compare and contrast familiar similarities of gestures and genetics while reflecting on how a single story can be told in as many ways as the number of people involved.

Taking into account the three generations of women who have varying queer/straight identities and familial origins in Texas, a new, more nuanced and complex story begins to unfold. The familiarity of the imagery pulls viewers in, connecting them to their histories. At the same time, the specificity of the artist’s experience presents an intimate investigation of a multi-generational queer family introducing a perspective outside of historical cannons.

Jensen Delius, Cotton Bowl from the Cadillac, Artist Book containing: Xerox image transfers of the artist, their mother, and their grandmother’s hands on Rives BFK paper, lithographically printed handwritten stories, original photographs, and a cover of found fabric from the artist’s mother, Page size: 5” x 7”

Editioning “traditional” processes requires time, exposure, and resources that become harder to access outside academic institutions. Artists with marginalized identities, like Jensen Delius, often experience a disparity of opportunities and access to print spaces. Addressing the flaws in this inequitable dynamic presents a moment for communal growth. Folding in perspectives from a more diverse landscape of artists can reinvigorate our structural view of the discipline, who it is for, and what it can create.

Can a repeatable matrix be a metaphor for a body in transition?

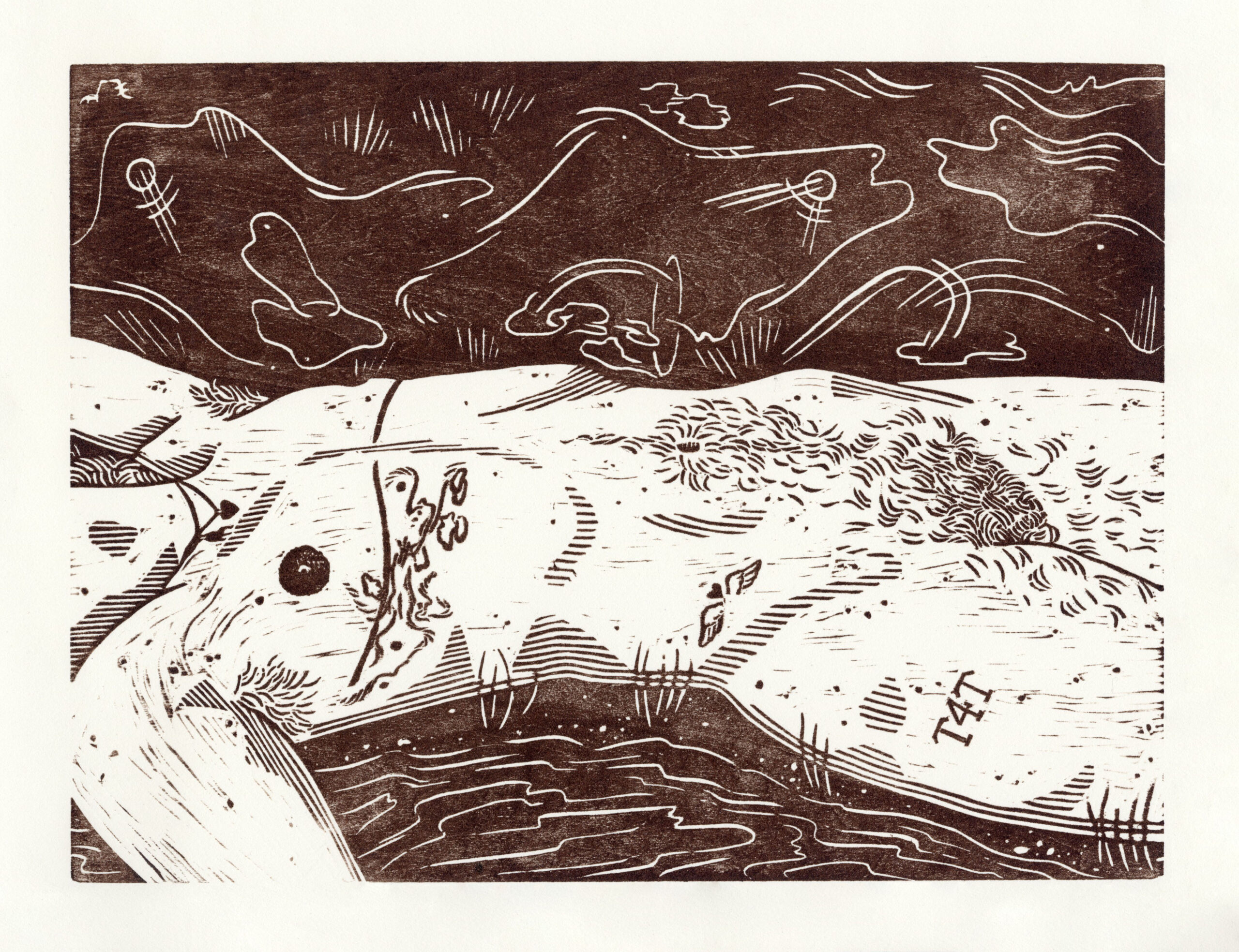

Juniper Darling’s (they/them) work displays the joyful experience of being a transgender person and humanizes a socially repressed identity. Utilizing images of trans folx in domestic routines and natural environments, Darling reorients harmful narratives that center medical history, sports performance, and bathroom usage to one of identity, love, and the human experience.

Juniper Darling, Carved and Outstretched, Woodcut, 10.5” x 13.5”

In Carved and Outstretched and Pasta Dinner, a light-skin transmasc person predominates the composition. While the cropped figure suggests a level of anonymity to the subject, allowing viewers to consider the experience of trans people in their own lives, the top surgery scars point to the specific history of an authentically lived life. The artist’s application of meandering, playful lines and vibrant compositions utilize print’s bold nature to depict poetic displays of internal self-discoveries and rituals. The posture of the figures communicates a confidence unabashed and unconcerned by social norms or taboos. The full and partial nudity of the subject is presented not for the viewer’s pleasure as a spectator but for communicating the feeling of being comfortable in one’s own skin. Darling’s courageous displays of self-awareness emphasize printmaking’s ability to advocate for self-discovery.

Juniper Darling, Pasta Dinner, Felt Embroidery, 10” x 9.75”

The technical process of printmaking engages various transitions: photograph to drawing, drawing to matrix, matrix to proof, matrix to edition, edition to exhibition. These transitions are not universal, nor are they always linear; however, they provide artists and printmakers with frameworks to process information and excavate conceptual ideas or narratives. As the key image or matrix is developed, the essence of the final work reveals itself before it is ultimately contextualized in an exhibition. Compared to the case of socialization, the process is reversed; familial definitions and community beliefs define individuals before they can form their own identities. Transitions are a part of life. Why not capitalize on an art form rooted in transitory states to help shepherd more tolerant belief systems?

Can a repeatable matrix be a tattoo gun for printing images on the body?

Emmalyn Mueller (they/them) and Jackson Shane (they/them) weave personal symbology, art history, and print aesthetics to push against representations of gender and provide folx the opportunity to reclaim their body.

Emmalyn Mueller, positioning the strawberry as a self-identified icon and metaphor within their prints, proudly describes themselves as “fruity,” rejecting the negative connotations of the word to describe queer people. Throughout their varied disciplines, they embrace bright and joyful hues. Mueller adorns their prints with beads and sequins, referencing material embellishments in drag culture. They push against patriarchal norms and promote safe, consenting spaces for their clients to decorate their bodies with rainbow-colored stars and patchwork squares, proudly displaying all colors of the proverbial rainbow.

Emmalyn Mueller, strawberry goose flash sheet, digital illustration, 8.5” x 11”

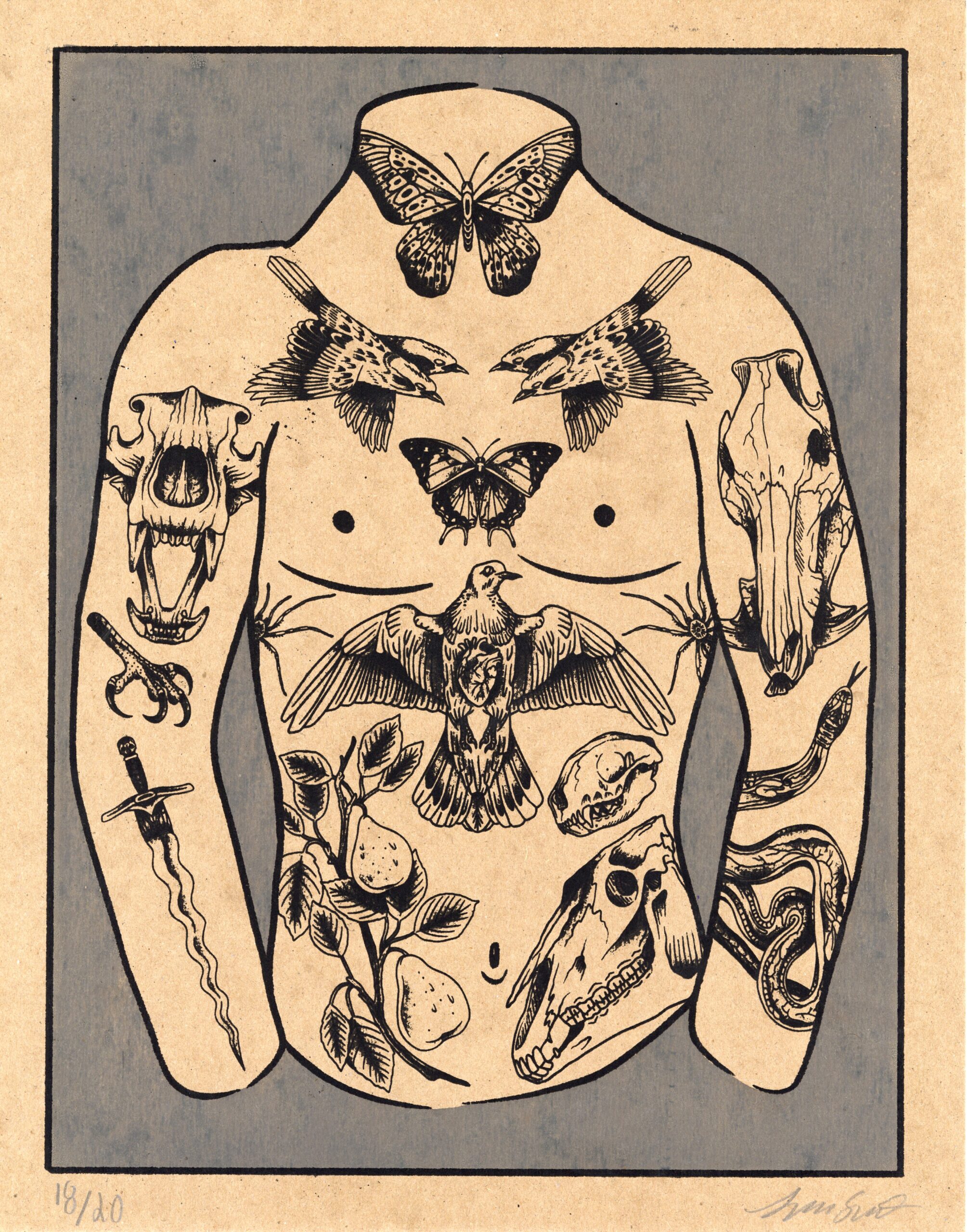

Jackson Shane takes a more traditional approach with the imagery in their tattooing practice. Informed by their experience growing up in Springdale, Arkansas, they design individual tattoos and sleeves composed of animal skulls, eagle claws, and various fauna. Their imagery is reminiscent of post-WWII era tattoo symbology. However, their refined linework originates from their experience with screenprinting. Shane publishes their flash designs as stickers, Riso prints, and screen-printed posters to compliment their tattooing practice.

Jackson Shane, Abdominal Layout 1, Screenprint, 12” x 14”

Mueller’s and Shane’s work have distinct styles with individual influences and origins; however, both tattooing practices create an intimate relationship between viewer and image, maker and participant. Both artists maneuver between drawing, tattooing, and printing, integrating three distinct processes. Emerging printmakers like Mueller and Shane demonstrate the potential for technical innovation when blending multiple craft-based technical processes and highlight the financial need to pursue opportunities in multiple fields simultaneously. This methodology of flexible making unites communities of artists, which is exactly what a print education strives to do.

Can a repeatable matrix be an action for an edition made up of a place, a plate, a print, and an idea?

Nicole Leung’s (they/them) practice challenges institutional frameworks regarding material hierarchy and traditional processes. Their site-specific installations, photographs, and prints depict conceptual actions rooted in questions of belonging. Images of vacant spaces, repelling magnets, and partially wiped plates call attention to subtle, quiet actions that grow and bloom when considering the artist’s intention for the action.

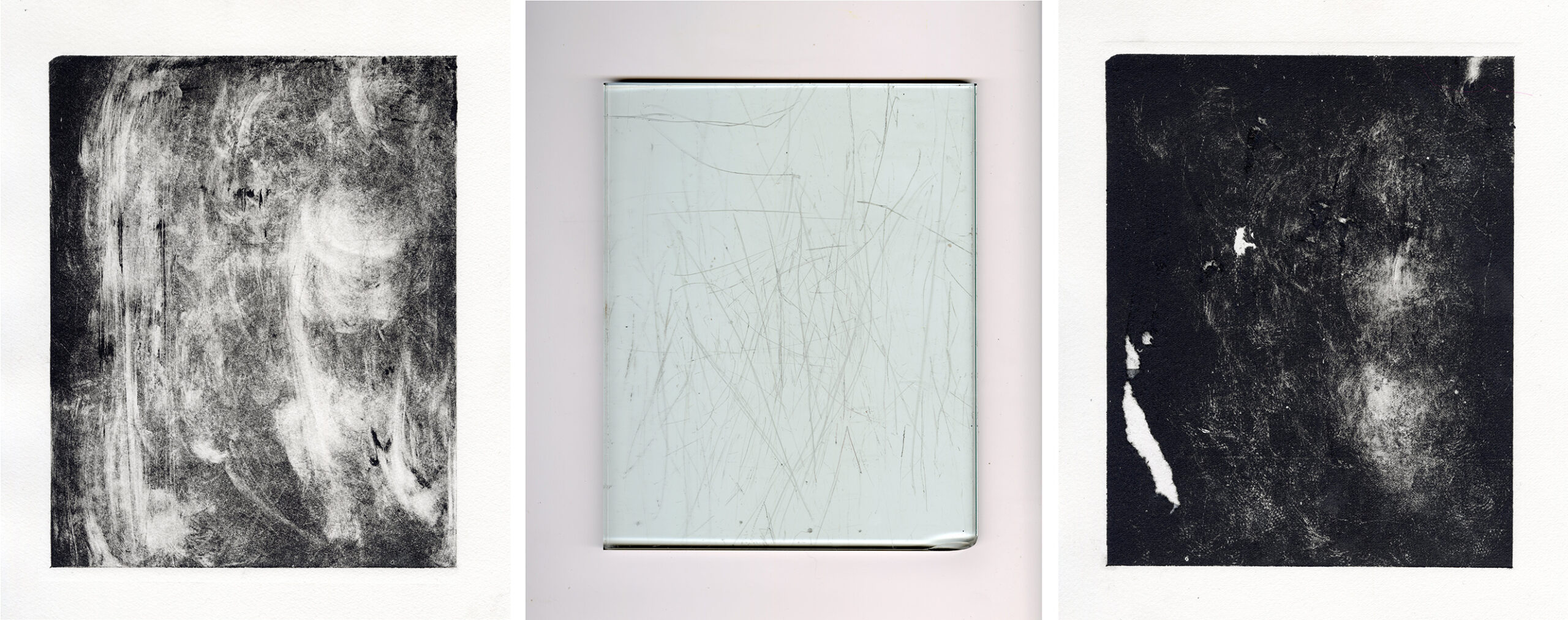

In the series Untitled, over a series of days, Leung dragged a glass plate across the ground and made impressions with the matrix. During the printing process, they intentionally removed ink by wiping in movements similar to the marks on the engraved plate. Rather than editioning a repeated image, the resulting prints have a linear descent in pigment, fading with every impression. By claiming the plate, the action imposed onto the glass, and the resulting prints as one multi-component piece, Leung challenges the structural relationship between matrix and print. Their work confronts us with the rigidity of labels and asks what constitutes a printmaking practice.

Nicole Leung, Untitled, Vitriography, Prints: 11” x 15”; Glass plate: 9” x 12”

Although art educational institutions were originally intended to foster free thought and experimentation, their dependence on corporate power structures and financial strategies has stifled academic integrity and streamlined creativity. Educational outcomes look for aesthetic consistency rather than unique displays of interpretation and performance. How many young artists turn away from printmaking due to losing points for the execution of craft, becoming overwhelmed by technical minutia, or not seeing their personal histories or ideas represented in the printmakers referenced in class? How could we redefine process versus product?

Can a repeatable matrix be a meme subverting pop culture?

For Babs Stevenson (they/them), when Columbia announced they would be cutting courses and part-time faculty, many of whom were influential to Stevenson’s education, the artist activated their voice. Stevenson applied print and graphic design strategies to help mobilize students and sign a protest petition. Their work, often inspired by memes and pop culture, advocates for marginalized positions with fun, approachable imagery.

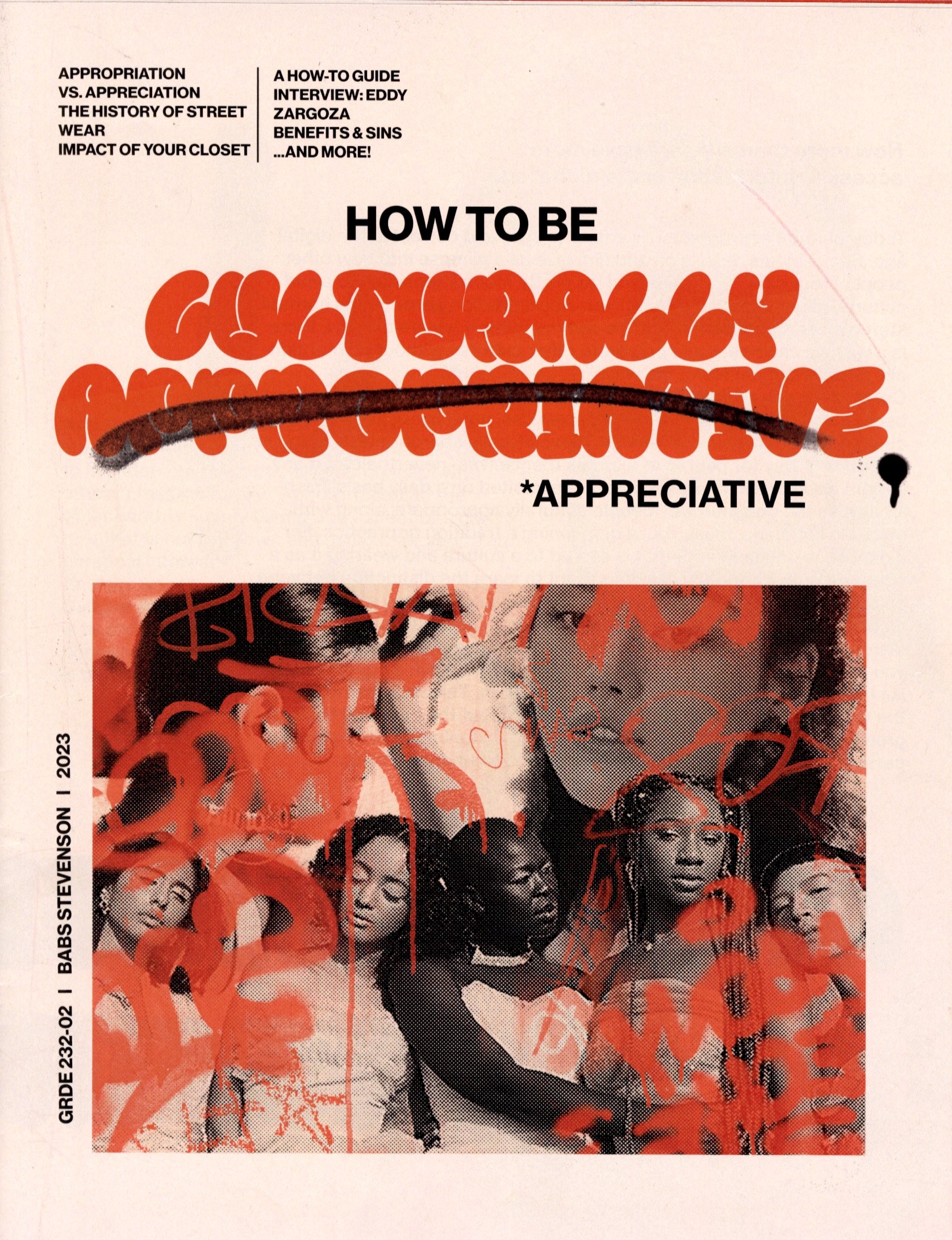

How to be Culturally Appreciative: A Guide for White People is a multi-page zine illustrating BIPOC perspectives on cultural appropriation. The publication’s design references fashion trends influenced by black culture, features graffiti fonts, and a color palette of various skin tones. To create this piece, Stevenson interviewed family and friends about their experiences and opinions on how white people can become more autonomous in unpacking harmful social trends. Stevenson, who is white, grew up with black family members. The experience of living in a multi-racial home introduced them to racial inequalities and racist norms, influencing them to incorporate antiracist educational materials into their practice.

Babs Stevenson, How to be Culturally Appreciative: A Guide for White People, Zine, Cover photo: 8.5” x 11”

Artists like Stevenson continue to broadcast the importance of speaking out and the power of an individual with a printmaking background to enact change and push against assumed norms. The activism created from a single text reorients the labor of understanding to the majority. Traditional printmaking methods find new relevance by subverting the mainstream vernacular.

Can a repeatable matrix be the instructor teaching students to make prints?

Jose Casales (he/they) has an important practice in print education with a unique trajectory. As an audio electronics major learning printmaking amidst the pandemic, Casales was introduced to the medium during quarantine. They had to adapt to making prints without a press and employ techniques and tools within his home. He continues to work out of his apartment, expanding his processes to include screenprint, relief (linoleum, Gelli, found objects), and monotype.

Casales utilizes these affordable and mobile print techniques to generate loud, energetic works that critique violence, celebrate perseverance, and call for liberation. They capitalize on iconographic palettes synonymous with the flags of Mexico, Palestine, Chicago, and the United States of America to bring awareness to social issues around the globe and connect viewers to a cultural identity. Within his practice, Casales uses the clown motif as an allegory for the complex way people present themselves publicly, hiding their authentic selves. The work nods to masking and/or code-switching as well as the performative labor required to navigate biased social systems.

Jose Casales, Know Fear, Screenprint on silver Duralar, 19.75” x 27”

Jose Casales now teaches various print methods, informed by his experience, to students at Marwen. Marwen provides free arts education programs to Chicago youth from under-resourced communities. In line with Casales, as print educators, we must continue working to create accessible models for folx to learn these techniques. Our ideas become stronger when vetted by diverse pools of thought versus our nerdy echo chambers. Like the artists in this exhibition, we must fearlessly hold on to what drives our passion in this process and leave behind the institutional baggage. Representation and inclusion hold the pathway to innovation and the future.

Can a repeatable matrix redefine the American story?

Printmaking is a widespread and globally diverse process for adornment, commerce, reproduction, and information sharing. However, definitions of prestige and success within the field continue to uplift academic performance. If academia/the “professional” printmaking community continues dismantling inequitable methodologies such as limited histories, process-based rubrics, and material hierarchies, new metrics for valuing prints will present themselves. Let us focus and reflect on the impact created by the artists, their intentions, and the circles in which they choose to operate rather than the conservative scales defined by institutions. What if we replaced Western, linear-based methods with open-ended exercises for exploration? How would prints look if we considered human-centered and culturally informed design thinking? Who could we attract to the medium if we adapted archival practices for accessible models that include materials from our daily lives?

In the end, Artists’ Proof poses the question, who better to lead us into a new way of understanding than the next generation?

Graphic Impressions is published by SGC International. SGC International is an educational non-profit organization committed to informing our membership about issues and processes concerning original prints, drawings, book arts, and handmade paper.

Graphic Impressions Updates

Submissions

We encourage your submissions to Graphic Impressions. Submission types include:

- Feature articles

- Reviews

- Interviews

- Studio visits

- Exhibitions

- Demonstrations or process-based content