Interview

Altered: An Interview with Eddy López and Carlos Barberena

Carlos Barberena (b.1972, Nicaragua) is a self-taught printmaker based in Chicago, recognized for his relief prints and the incorporation of images from pop culture alongside reflections on sociopolitical and cultural tragedies.

Barberena has received various awards, most notably: “The Otis Philbrick Memorial Prize” Boston Printmakers: 2023 North American Print Biennial. Boston, MA; “The Elizabeth Catlett Memorial Award”, MAPC, University of Iowa; Second Prize in the 13th BIECTR, Quebec, Canada; The National Printmaking Award, Nicaragua. His work is included in public collections such as the Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach,; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago; The Chicago History Museum; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Ortiz-Gurdián, Nicaragua among others.

Barberena is a core member of the Instituto Gráfico de Chicago.

Artist statement

My work consistently reflects on the cycles of repression and resistance, and their connection to the Diaspora I have experienced—navigating periods of dictatorship, revolution, erasure, renewal, hope, and repression. I create to highlight the overlooked protagonists in our collective well-being and bring awareness to our linked struggles for social, political, economic and environmental justice.

As a refugee and migrant, my art addresses migration, violence, war, revolution and social change from a unique, multi-angled perspective, advocating through work portraying daily struggles for dignity and basic rights.

For me art also serves as a site of auto-ethnography, through my work, I explore how my own experiences relate to those of other marginalized and organized communities globally, and how broader social, economic, and political forces shape these experiences.

Eddy López

Website: eddyalopez.com

Eddy A. López, born in Matagalpa, Nicaragua in the midst of the Sandinista revolution, is a printmedia artist whose work explores collective memory and trauma as a result of war. His work has been exhibited at the the International Print Center New York, The Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, the Janet Turner Print Museum, the North American Print Biennial, ArtMiami, among others. His recent exhibitions include “X Factor: Latinx Artists and the Reconquest of the Everyday” at the USF Contemporary Art Museum, “Versos” at the Doris Ulmann Galleries at Berea College, and “Beautiful War” at the Carroll Gallery in Huntington, WV, and the Samek Art Museum in Lewisburg, PA. He is the recipient of various awards and grants including an Andrew Mellon Foundation Fellow. López’s work can be found in the collections of the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Frost Art Museum, Zuckerman Museum of Art, Jaffe Center for Book Arts, and more.

López received an MFA in printmaking from the University of Miami, and a BFA in Painting and Printmaking as well as a BA in Art History from Florida International University. Currently, he is an Associate Professor of Art at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

Artist statement

My artwork is an exploration on the ethics of representation and the perils of nostalgia using archives of war, particularly from the conflicts in modern Nicaraguan history. I use print media and its processes to try and find meaning in a chaotic world by transforming collective memory and trauma into obfuscations of colors, patterns, and shapes.

As a survivor of war and a war refugee, I explore the relationship between lived experience and representation, between remembering and forgetting. My work searches for the proper artistic response to pain and suffering and interrogates whether it is right to seek inspiration from atrocities.

Through these compositions, I explore my experience as a contemporary artist in the age of big data, social networks, and the 24-hour news cycle. Here, the burin, ink, and pixel make the most sense.

The Interview

Blake Sanders: You were both born in Nicaragua, growing up around the Sandinista revolution. Your paths to the US, as I recall, were quite different. Could you please share a bit about your motivations to emigrate, the process that brought you to America, and how that experience influences the content of your artwork

Eddy López: I wasn’t motivated to come to the United States so much as I was forced to migrate as a child due to the violent civil war that was ravaging my home country (ironically, that war was fomented by the United States, the country that became my adopted home.) My parents did not want me to be drafted as a child soldier to fight in the war, so they sent me with one of my older sisters to Mexico, where we crossed the Tijuana-San Diego border undocumented with the help of coyotes in June of 1987. We then sought asylum as war refugees in this country, which was granted the following year.

As a child, I did not understand the war and refugee experience I lived through. Therefore, one of the things I’ve tried to do as an artist is to create print media work that deals with the memory and trauma born as a result of war and the diasporic experience. I work to transform these experiences into prints that seek meaning out of that chaos. My work is also about critiquing, and raising awareness about, the socio-political forces that create these upheavals — to question the complicated power dynamics that have besieged Nicaragua and Latin America.

Eddy Lopez

La Prensa (Resistencia Ciudadana)

Screenprint, archival digital print

Composite of La Prensa covers from the 2018 uprisings in Nicaragua

44″ x 30″

2019

Carlos Barberena: I left Nicaragua on November 3, 1986, due to the civil war, the U.S funding of the Contras, and an economic embargo imposed on Nicaragua, my family faced immense pressure. My older brother, who had fought with the Sandinista guerrillas, had left the country a few years prior, and my other brother was in obligatory military service. When military service agents threatened my mother that I would be taken if my older brother did not return, my mother decided to send me to Costa Rica for my safety. I crossed the border alone at 14 years old and remained undocumented for nearly two years before I could apply for asylum, which was approved a year later.

Twenty-two years later, I made the choice to come to the United States. My wife wished to pursue a Ph.D. in Anthropology, and I sought to continue and expand my artistic career beyond Central America, where I felt my opportunities were limited.

My art practice is deeply influenced by my experiences as a refugee and migrant, along with the harm caused by U.S. interventions in my home country. I consistently explore themes of repression and resistance, and their connection to the diaspora, reflecting on cycles of dictatorship, resistance, revolution, erasure, renewal, hope, and repression.

I examine how global politics and late capitalism contribute to repression and affect daily life, aiming to highlight overlooked individuals who contribute to our collective well-being. My work seeks to raise awareness about our interconnected struggles for social, political, economic, and environmental justice.

Carlos Barberena

Libertad

Linocut

15” x 11”

2019

BS: Eddy attended Florida International for undergrad and University of Miami for your MFA, both with an emphasis in printmaking. Carlos, on the other hand, is a self-taught printmaker. When did you both first encounter printmaking, and how did you know it was for you? How do you think your differing educational experiences influenced the development of your work?

CB: Printmaking has always been a significant part of my life. During the revolution, many artists and printmakers came to Nicaragua to teach and create work focused on the revolution and social movements. As a child, I was surrounded by relief prints and screen prints that my brother brought home during his military service at the Ministry of Propaganda.

When I began creating art, I explored various techniques, but it wasn’t until 2002 that I truly engaged with printmaking. That year, the German artist Wolfgang Hunecke visited my hometown in Nicaragua and invited me to a two-week intaglio workshop at Casa de los Tres Mundos in Granada, Nicaragua. There, I learned etching, aquatint, and drypoint techniques.

Although that was my initial experience, I didn’t return to printmaking until 2007 during an artist residency at the Ex-Convento Jesuita Printshop in Patzcuaro, Michoacan, Mexico. The following year, after moving to the USA, I joined Expressions Graphics, a printmakers’ cooperative in Oak Park, Illinois. I spent several years creating and producing work there, in addition to my independent projects, Bandolero Press and La Calaca Press. In 2014, I joined the Instituto Grafico de Chicago, a collective of Latin American and Latine printmakers based in Chicago, solidifying my passion for printmaking. The rest, as they say, is history!

Exodus

Linocut

24” x 18”

2019

EL: I was first seriously introduced to printmaking through a print class taught by Alberto Meza, a Chilean printmaker who taught at Miami-Dade Community College, which is where I earned an associate degree in Fine Art. Meza’s enthusiasm for the medium was contagious. I soon developed a passion for working in the printshop, with all its sensory experiences: handling the presses, smelling the inks, hearing the screeching sounds of filing a plate, and — of course — the satisfaction of holding a finished print. The whole thing tenia sentido — it made sense to me. So when I transferred to FIU (a state school), I continued taking print classes under Richard Duncan. Later on, I completed an MFA under Lise Drost at the University of Miami.

Working in the university printshops allowed me to experiment under the tutelage of a mentor, learn from visiting artists, and have access to a shop 24/7. I took advantage of the space to experiment — and fail — under the mentorship of these master printers. I learned so much by just struggling through the processes and then asking my professors what went wrong (and right) in my prints. The colleges would bring visiting artists to campus to work in the shops, and being able to see and learn from these individuals was invaluable. Because my education took place in Miami with its vibrant Latinx population, several Cuban and Latin American masters came into the shops to print, and I got to learn from their bag of tricks. I had access to fully-equipped shops where I would try out all of the techniques I’d seen demonstrated.

I also want to mention the importance of place in my development as an artist. Living and studying in South Florida allowed me to stay connected to my Nicaraguan and Latin American roots. It also facilitated travel back to my home country, making it easier for me to visit the place where I spent formative childhood years. All of these experiences fed into my identity and worldview as an artist/printmaker.

Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy, by Paul Dix, Pamela Fitzpatrick

Archival digital print

Composite of the book Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy

36″ x 65″

2018

BS: You’re following different paths professionally as well. Carlos is producing prints at Bandolero and La Calaca Presses and remains community focused with Instituto Grafico de Chicago. Please share for our readers how these entities came to be and how you have helped maintain and grow them over the years. How does your experience as an independent artist free you to produce your unapologetic work? What are the downsides of that independence?

CB: I established Bandolero Press in 2009, initially operating from my kitchen table to produce my first portfolio, “Años de Miedo / Years of Fear.” Since then, it has grown into a larger space in my basement. My vision for Bandolero Press was not only to create a platform for publishing my own work but also to collaborate on other projects and provide a resource for printmakers who lack access to a printing press to produce their editions. In the future, I plan to publish works by emerging BIPOC printmakers, supporting their artistic development and increasing their visibility within the printmaking community.

In 2011, I created La Calaca Press International Print Exchange project to build bridges between printmakers worldwide and those in Nicaragua. We have successfully completed three editions involving 150, 200, and 250 printmakers respectively, with numerous exhibitions in a dozen of countries.

The Instituto Grafico de Chicago was founded in 2010 in response to the underrepresentation of Latinx artists in Chicago’s printmaking exhibitions and festivals. We are a collective of printmakers, educators, studio artists, arts administrators, and teaching artists who live and work within Chicago’s Latinx communities. As grassroots printmakers, we are dedicated to building community and continuing the legacy of printmaking through international art exchanges and public educational spaces. We exhibit our portfolios across the U.S. and Mexico, and our participatory workshops engage Latinx communities in the Midwest, inspiring new generations to embrace printmaking as a social force.

Keeping these projects running and growing presents significant challenges, primarily due to self-funding. However, our love and commitment to our community are the driving forces that allow us to persist.

As an independent, self-taught artist, a major challenge I’ve faced is the lack of funding and opportunities available to individuals without an art degree. In Chicago, there is only one institution that offers a mini-grant specifically for self-taught artists. I have personally experienced difficulties in securing opportunities and equitable payment solely because I do not possess a formal degree.

Mater Dolorosa

Linocut / Gráfica América print portfolio

30” x 22”

2019

BS: Eddy is teaching at Bucknell University. How does the academia’s research structure allow you paths to disseminate your message? Are there ways in which the model hampers your creativity/expression? How does your approach in the classroom complement your artistic practice and mission and vice versa?

EL: Working at Bucknell has been greatly rewarding, both as a professor and an artist. First and foremost, I enjoy teaching. It’s always a pleasure to see students develop as artists and printmakers, to challenge themselves to create work that is meaningful to them. Bucknell is a research-heavy liberal arts college, so professors are expected to be active in their fields. Sometimes, it’s hard to balance a teaching load with a research load — the semesters when I have a solo-show coming up are very trying. Overall though, the university environment has been supportive of my work, giving me the space and access to a shop that has allowed me to develop a number of print series without impediments.

During my time at Bucknell, I’ve focused on exhibiting at mostly non-profit art centers, having shows and talks at universities, joining print exchanges around the globe, attending conferences (many SGCIs!), and engaging with a wide variety of students, faculty, and community members. I feel very at home in a college environment, and my work and creative expression has not been hampered — although, under this new authoritarian Trump administration, I expect to see more dictates and orders coming from the oval office aimed at censoring the type of work I do in academia.

Adios Muchachos

Photopolymer etching

Composite of Sergio Ramirez’s revolutionary memoir, Adios Muchachos

9” x 12”

2022

BS: Both of your work relates at least in part to censorship, repression, and erasure. How does this relate to your upbringing around revolution and political upheaval? In what ways did that initial formative kernel germinate into the thoughtful work you make today?

EL: One of the things that I learned early on, as a child growing up in a war zone, was that artists could — and should — play a crucial role in shaping a country, both socially and politically. Many artists were committed through their work to creating a better Nicaragua, and I saw this in the revolutionary murals painted by artists like Leoncio Sáenz, in the Nueva Canción music that would play on the radio by musicians like Carlos Mejia Godoy, and especially in the poetry and writings of authors such as Gioconda Belli, Ernesto Cardenal, and Sergio Ramirez. These artists taught me a way to tackle the existential issues of living, resisting, and thriving under the shadow of repression and war.

Beautiful War I: Nicaragua, by Susan Meiselas

Archival digital print

Composite of the book Nicaragua by Susan Meiselas

40″ x 59”

2023

CB: As Eddy mentioned, artists in Nicaragua were committed to rebuilding the country after almost 45 years of the Somoza dictatorship. Immediately following the triumph of the revolution, the Ministry of Culture was created, which brought many artists—including printmakers, poets, musicians, and filmmakers—to the country. The Ministry of Culture opened numerous Popular Culture Centers to provide free access to art for the public. However, I believe one of the most important campaigns was the National Literacy Crusade. Nicaragua’s literacy rate was only 50%, and with the crusade, it grew to 88%.

I believe this was a time of both inspiration and resistance. When I reflect on that period, Nina Simone’s quote always comes to mind: “It’s an artist’s duty to reflect the times in which we live.”

Abolish ICE

Linocut

24” x 18”

2021

BS: In 2024 you were involved in the Show Me Your Papers panel and exhibition at the Providence conference relating your immigrant experience and discussing the uncertain future. The exhibition was recently hosted again at CUNY Staten Island and at the Samek Art Museum. How has the current political landscape altered your experience with the work? How has the response to the show shifted? What has remained largely the same?

EL: Miguel Aragón and I co-curated this exhibition back in summer of 2023 for the Providence conference. Immigration was an issue way before then. It was an issue when the show debuted at the Public Gallery in Providence. It is an issue today as the show wraps up another stop at Western Michigan University. And, unfortunately, it will still be an issue into the future. The works in Show Me Your Papers are focused on the immigrant experience, and aim to bear witness to the treatment of migrants in this country and across the globe.

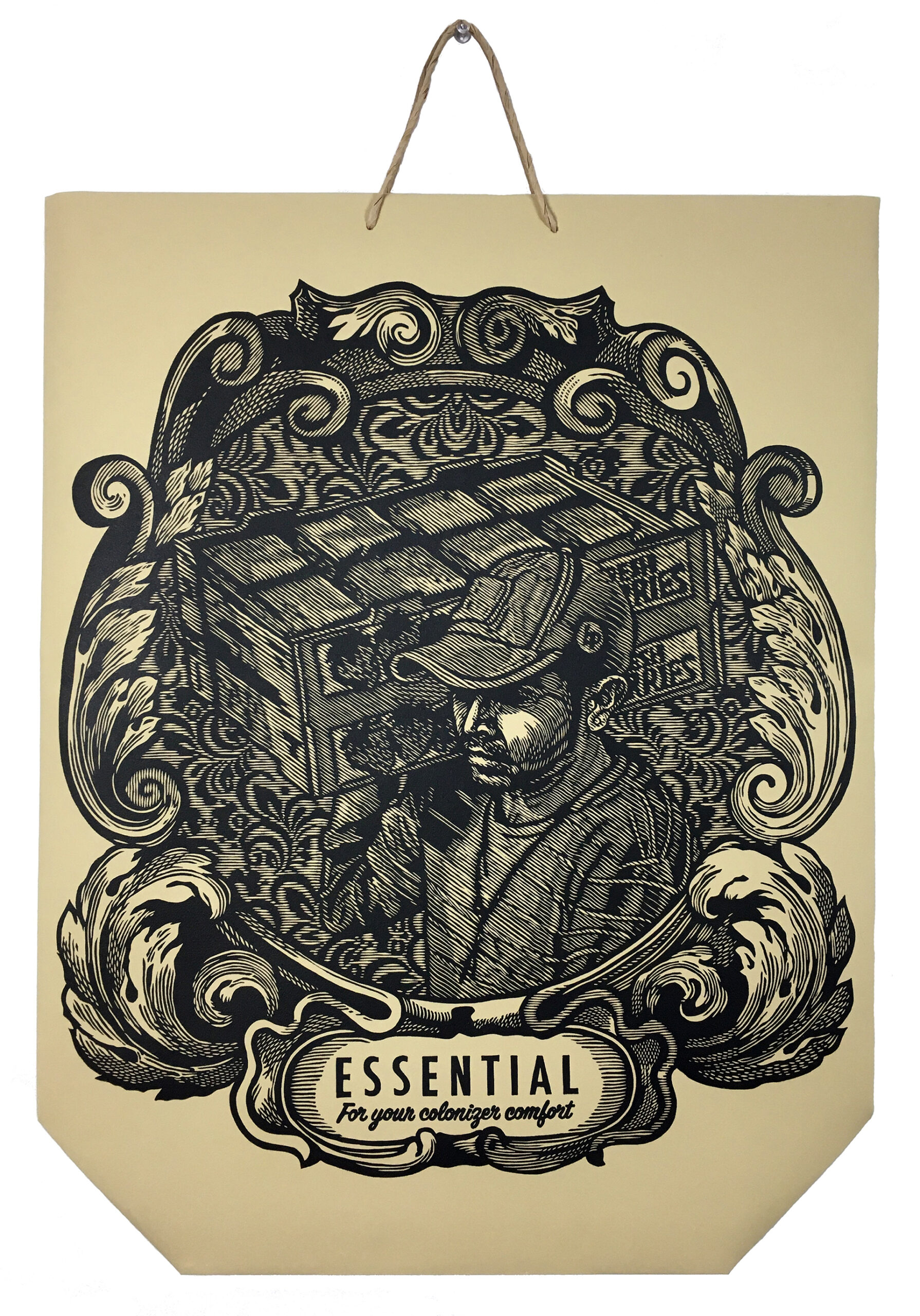

One of the works, a beautiful lithograph by Juana Estrada Hernandez called “Nopalaso en Nombre de Nuestras Familias,” shows a child resisting the arrest of a loved one from ICE. That powerful print is from 2021, and it is even more powerful today because life for immigrants has gotten worse under the ICE-on-steroids of the second Trump administration. Carlos Barberena also has a number of prints from his “Essential: For Your Colonizer Comfort” series, which centers immigrant workers who were deemed essential workers during the COVID pandemic. Audience members are in awe of the masterful carvings in his prints, and the juxtaposition of these incredible portraits printed onto shopping bags. Overall, the show has gotten a tremendous response — we’ve had great reviews from gallery attendees and the media.

Regarding the political landscape, in the gallery and panel talks I’ve given related to the show, I highlight the fact that the United States has not had any major immigration reform legislation in over 20 years. Congress, under the second Bush administration, throughout the Obama years, Trump v.1, Biden, and now Trump v.2, cannot get its act together and pass updated immigration laws. This inaction set the ground for things like Obama’s large numbers of deportations, the DACA executive order, and the latest authoritarian response by the Trump administration, which has been cruel and violent. In many ways, Trump and ICE are sad reminders of the xenophobia that has been present in this country since its founding. Show Me Your Papers, a show that is also about compassion and empathy for immigrants, plays a small part in the artistic resistance to this inhumane treatment.

Memoria Grafica (Resistencia Ciudadana)

Archival digital print

Composite of photographs from the Nicaraguan uprisings of 2018

36″ x 50”

2019

FYW

Linocut

18” x 24”

2019

BS: You’re both making work that is foundationally political. What has been your experience with censorship or cancellation of your work? How has your content or approach shifted as a result? Are you finding the audience for this work changing, or perhaps merely the opportunities to present the work publicly?

CB: I returned to Nicaragua in 1993 after seven years in exile, and from then on, I traveled frequently between Nicaragua and Costa Rica. In 1997, I held my first solo show in my hometown, featuring paintings that explored syncretism, colonization, and native roots. One of the pieces was unfortunately destroyed by visitors.

In 1998 I moved back to Nicaragua to establish my career. In 2000, I presented my second solo exhibition, “Años de Miedo,” a series of paintings and installations reflecting on my personal and collective historical memories of the civil war in the 70s and 80s. This work explored how these memories and fears affect our lives, both physically and psychologically. The exhibition also served as a response to the pact between the two major political parties who “shared the cake of power,” which ultimately paved the way for the current dictatorship.

The exhibition was hosted by Praxis Gallery, a historically significant place of resistance during the dictatorship, at the time of my exhibition the gallery was government-subsidized. My show was briefly censored two days before the opening, with the power, phone line, and water all cut. Fortunately, it was reopened just in time through the influence of the future mayor of the capital. I was lucky not to end up in jail or have my work destroyed, as happened to several artists years after my exhibition. Currently, it is uncertain if I can visit my country after producing work related to the 2018 uprising.

Here in the U.S., I have also experienced some censorship. I discovered that a couple of my pieces in a university show in Oregon were removed after the opening; I was not notified and only learned about it from a student a couple of years later. More often, however, it has been through the rejection of pieces for shows or juried exhibits—ironically, these have often been pieces that have received international awards or are now in museum collections.

Undocumented

Linocut on a shopping bag

24” x 18.5” x 7”

2020

EL: When you make art that is political and challenges power — especially in the context of an authoritarian regime — you’re going to face censorship. My work has not been censored in this country, but it has been softly-censored in Nicaragua. I say “softly” because a solo exhibition of my work was cancelled due to the political situation in the country (Nicaragua is currently under a dictatorship now nearing 20 years in power.) Essentially, the gallery did not feel comfortable exhibiting the work without facing repercussions, and I did not want to put the folks that run the space in danger. While I have found other ways of having my work shown in the country, it has been very limited in scope.

Unfortunately, this is an all too common experience that artists face under authoritarianism as galleries avoid exhibiting certain art out of fear for what could happen. What you then have is a repressive state, where freedom of expression is curtailed and artists have to find alternative venues for displaying their work — in hidden spaces and publications, online, and outside the country.

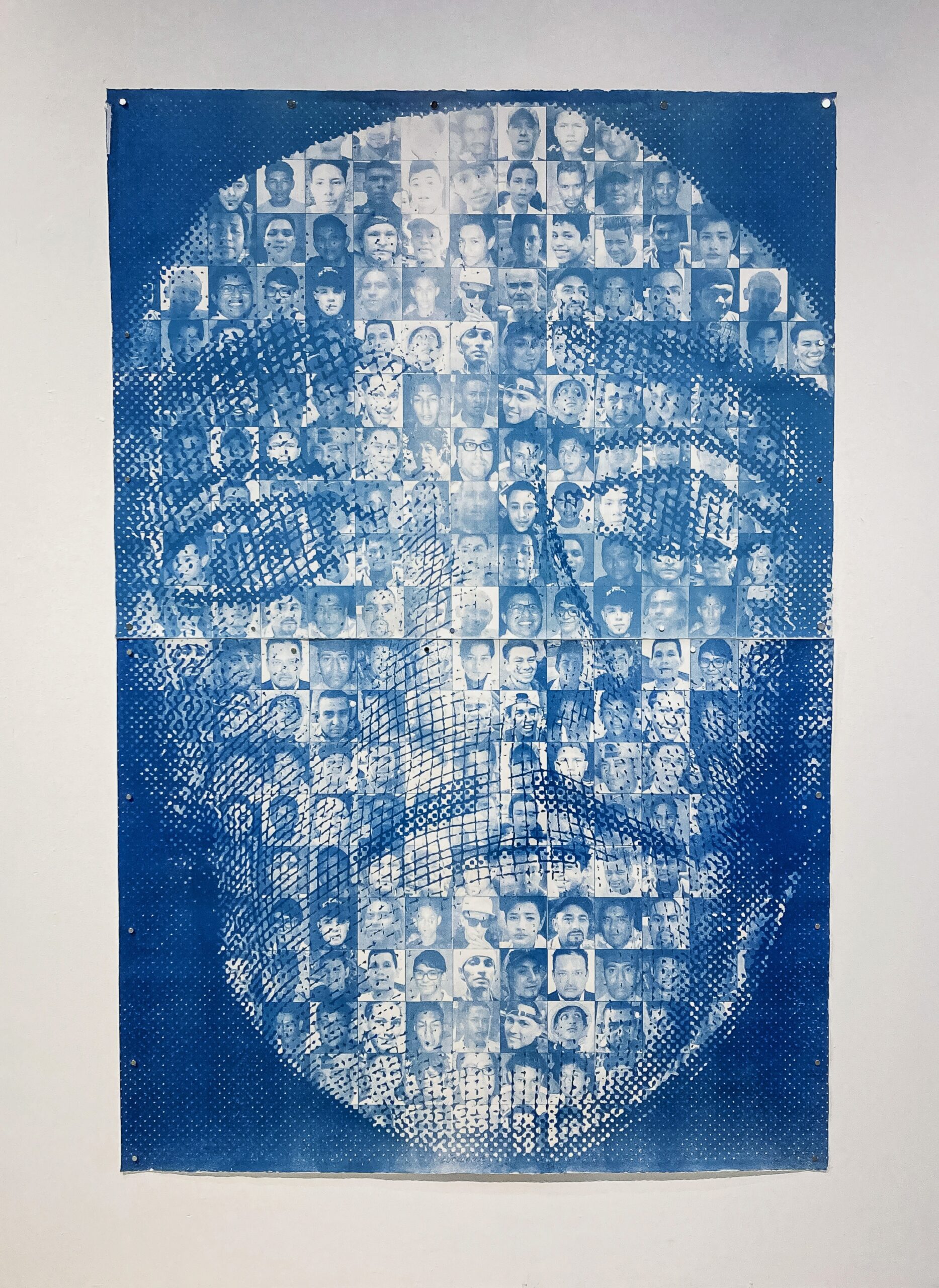

Gueguense

Cyanotype

Faces of student protestors killed during the popular insurrections in Nicaragua of 2018

84″ x 55″

2021

BS: The emphasis on immigration enforcement and the recent Supreme Court shadow docket decision to authorize federal personnel to employ racial profiling increases the existential threat on immigrants, more accurately, all non-anglo people in the US. How is this looming pressure influencing your work, your productivity, and your day to day life? How does this pre-meditated cancellation conflict with the promise of American freedom the US is so quick to promote?

CB: I have deep concerns about the current political climate in the United States, which, based on my personal experiences with dictatorships and authoritarian governments in Latin America, bears unsettling resemblances to the early stages of those regimes.

The ongoing paramilitary occupation in Chicago is causing immense trauma and pain within our communities. The fear is palpable in our neighborhoods, and the live-streamed kidnappings and separation of families are clear violations of human rights and the U.S. Constitution. While many may not yet fully recognize the gravity of the situation, I believe it is critical to acknowledge these alarming developments.

Fortunately, Chicago has a rich history of civil rights activism and community organizing. Our communities are actively resisting this paramilitary occupation through rapid response initiatives, “Know Your Rights” workshops, neighborhood safety organizing, distribution of whistles to alert residents to ICE presence, and fundraising to support affected families. While the resilience of Chicago’s communities is strong, we urgently need the support of everyone across the country to stand with us.

No Human is Illegal

Linocut on a shopping bag

24” x 18.5” x 7”

2020

EL: As a first generation immigrant, this new reality hits home in multiple ways, both professionally and personally. It’s been really hard to see how Trump’s executive orders and the Supreme Court’s decisions are affecting artist friends who are avoiding travel to exhibitions and conferences due to fears of getting detained. For example, multiple friends cancelled travel to the SGCI Puerto Rico conference out of that fear. Personally, I have family members affected by the threats of deportation, and seeing them live in fear is nerve-wrecking. All this chaos is influencing the work I’m producing in the studio — there’s no way it can’t. The violence takes a toll. Some days it’s hard to make sense of things, but I take a step back, regroup by spending time with my family, and continue.

My concept of freedom has been shaped by living in Nicaragua and the US. In Nicaragua, we have seen freedom of expression vanish from the public sphere. It’s a heavy absence that’s made me realize what it means not to have liberty. In the US, we can still voice our opposition to the government. But I feel the effects of government repression in this country growing, palpably, every day. Freedom of expression is being restricted by the state– from the tracking of social media posts for anti-Trump messages, the cancelling of talk shows for critiquing the president, the banning of books, to the termination of exhibitions and residencies for “DEI” content. All of this reminds me of what happened in Nicaragua as the dictatorship asserted its power.

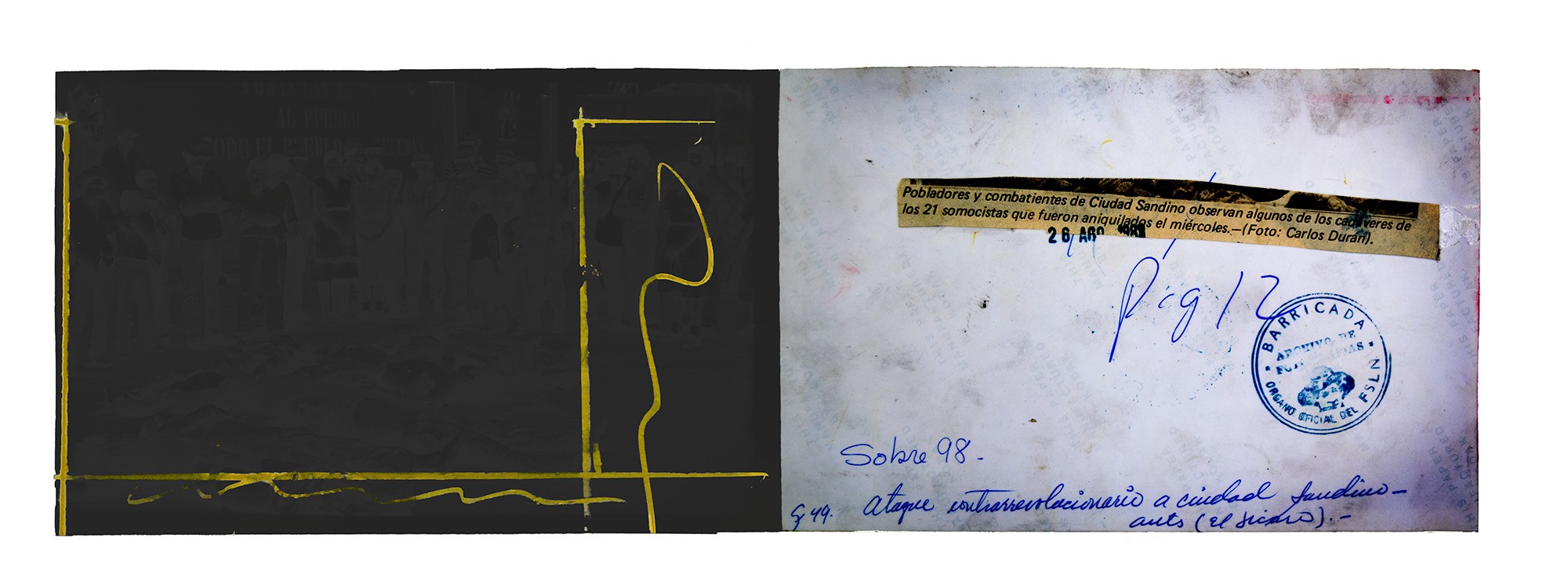

verso i (ataque contrarevolucionario)

Screenprint, archival pigment print on Moab Entrada

20” x 42″

2023

BS: Let’s try to end on a high note. Where do you find hope? How can we steward the good we find to become meaningful change? What is coming next for each of you, whether it’s new work or new opportunities that you’re excited to share?

EL: For hope, I look at my daughter and think about how she’s the future. Looking at her gives me the hope and energy to keep working to make this earth a better place for her and future generations. I also look at what other artists did when faced with the injustices of their day — people like Victor Jara, Elizabeth Catlett, Lotty Rosenfeld, Yolanda López, Ernesto Cardenal. They all spoke truth to power. And I always keep close to my heart a quote from Gioconda Belli’s The Country Under My Skin: “I dare say, after the life I have lived, that there is nothing quixotic or romantic in wanting to change the world. It is possible. It is the age-old vocation of all humanity. I can’t think of a better life than one dedicated to passion, to dreams, to the stubbornness that defies chaos and disillusionment.”

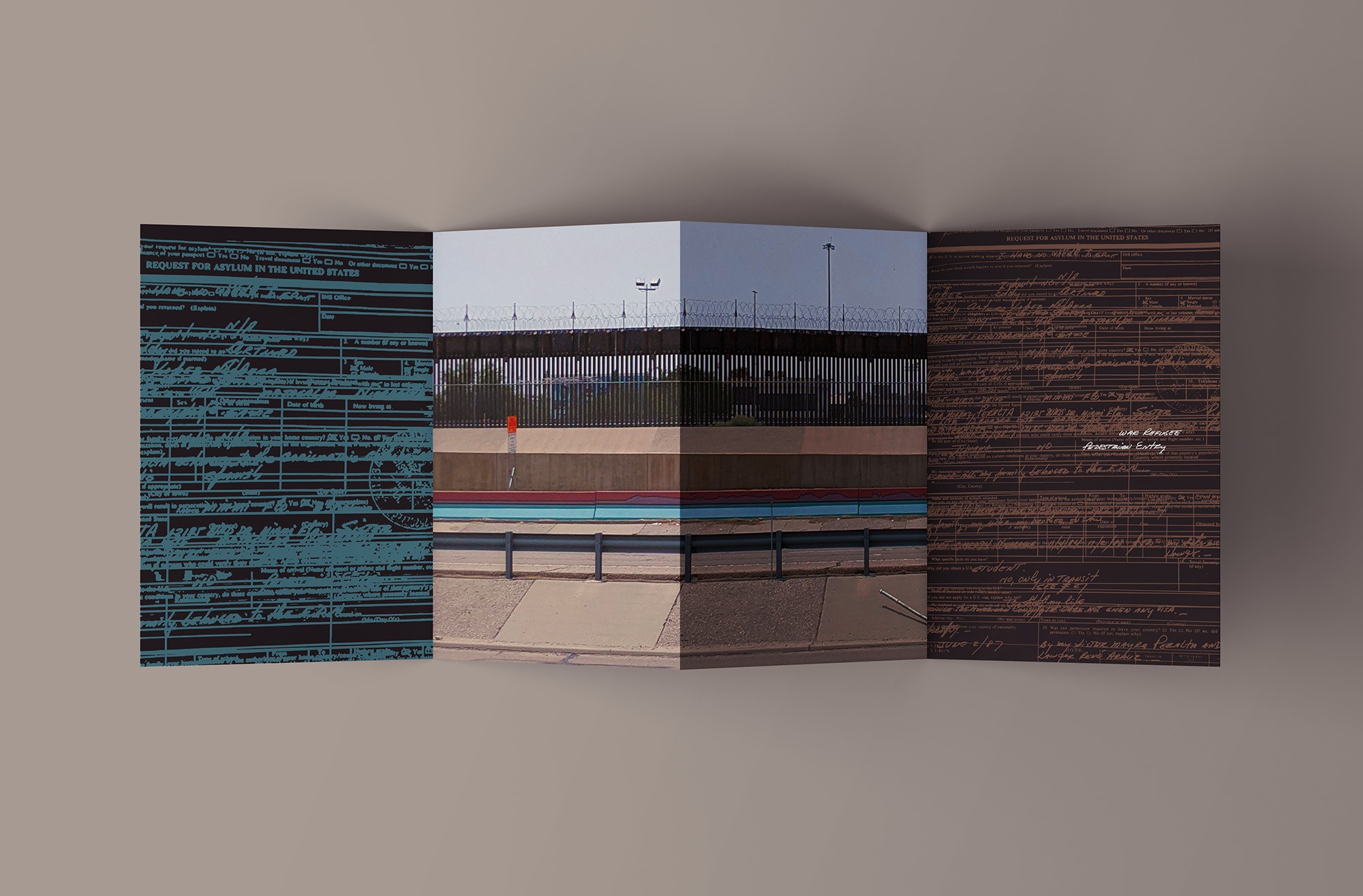

Pedestrian Entry II

Screenprint, archival digital print

10″ x 27″

2022

In-Dependencia

Screenprint on fabric

Dimensions variable (each flag is 3’x5′)

2021-2022

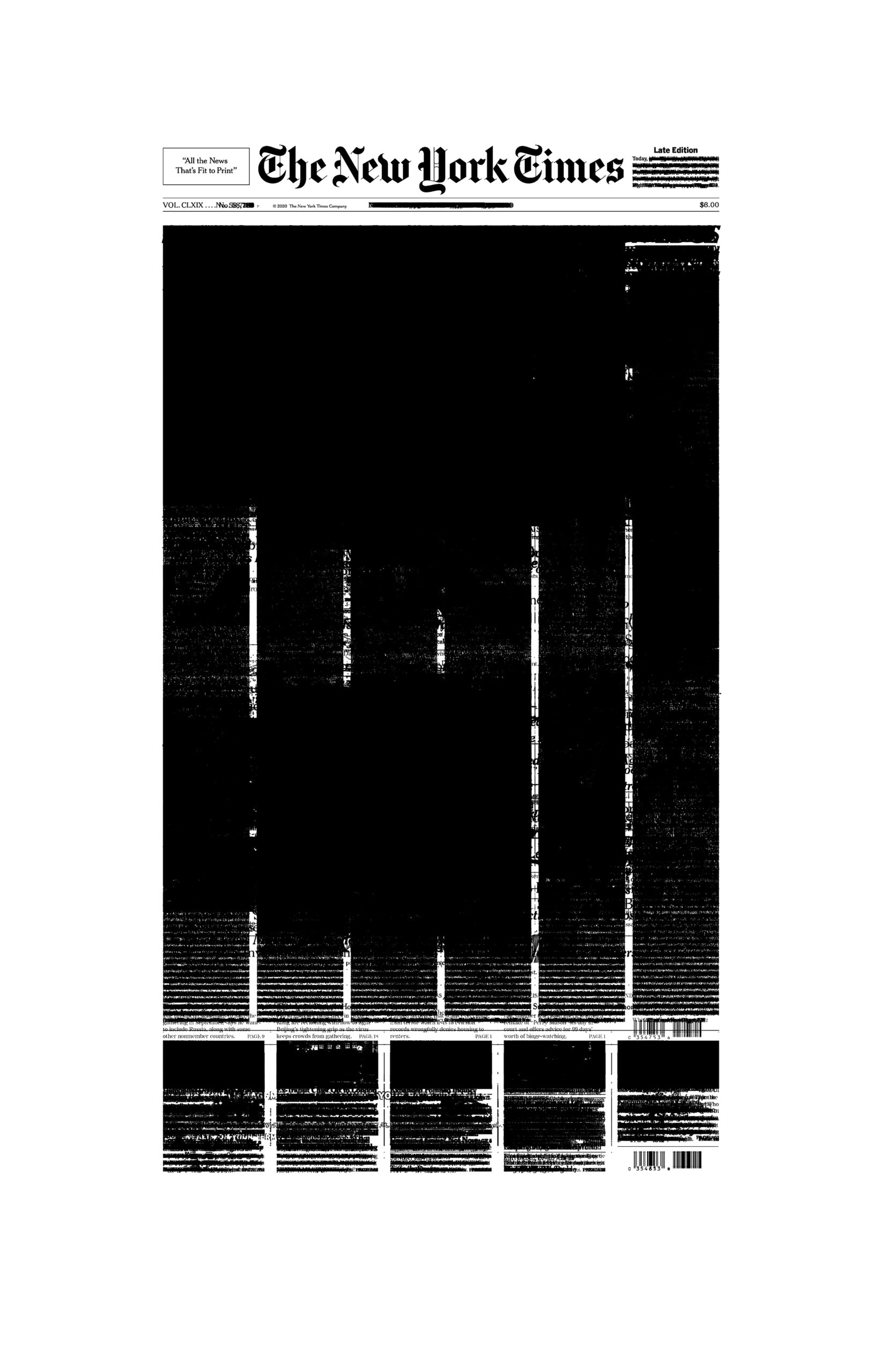

NYTimes BLM III

Screenprint

28″ x 18″

2020

CB: Solo el Pueblo Salva al Pueblo / Only the people can save the people

There are days when the scale of global injustices—the collapse of democracies, the resurgence of fascism, the genocide in Gaza, human disconnection, environmental disasters, and the most egregious forms of capitalism—can feel overwhelming and lead to a sense of hopelessness.

However, there are also moments when I witness people uniting to fight and resist oppression, and in those moments, I believe we also deserve to win. I think of all the artists throughout history whose work fostered critical thought and created consciousness in their times, often utilizing printmaking as a powerful tool.

It is my hope to continue using printmaking as a vital medium for communication and resistance during this period of sociopolitical unrest, raising our voices against totalitarian regimes and fascism, especially when other forms of expression are suppressed.

Keep spreading the ink!

Strawberry Fields

Linocut on a shopping bag

24” x 18.5”

2020

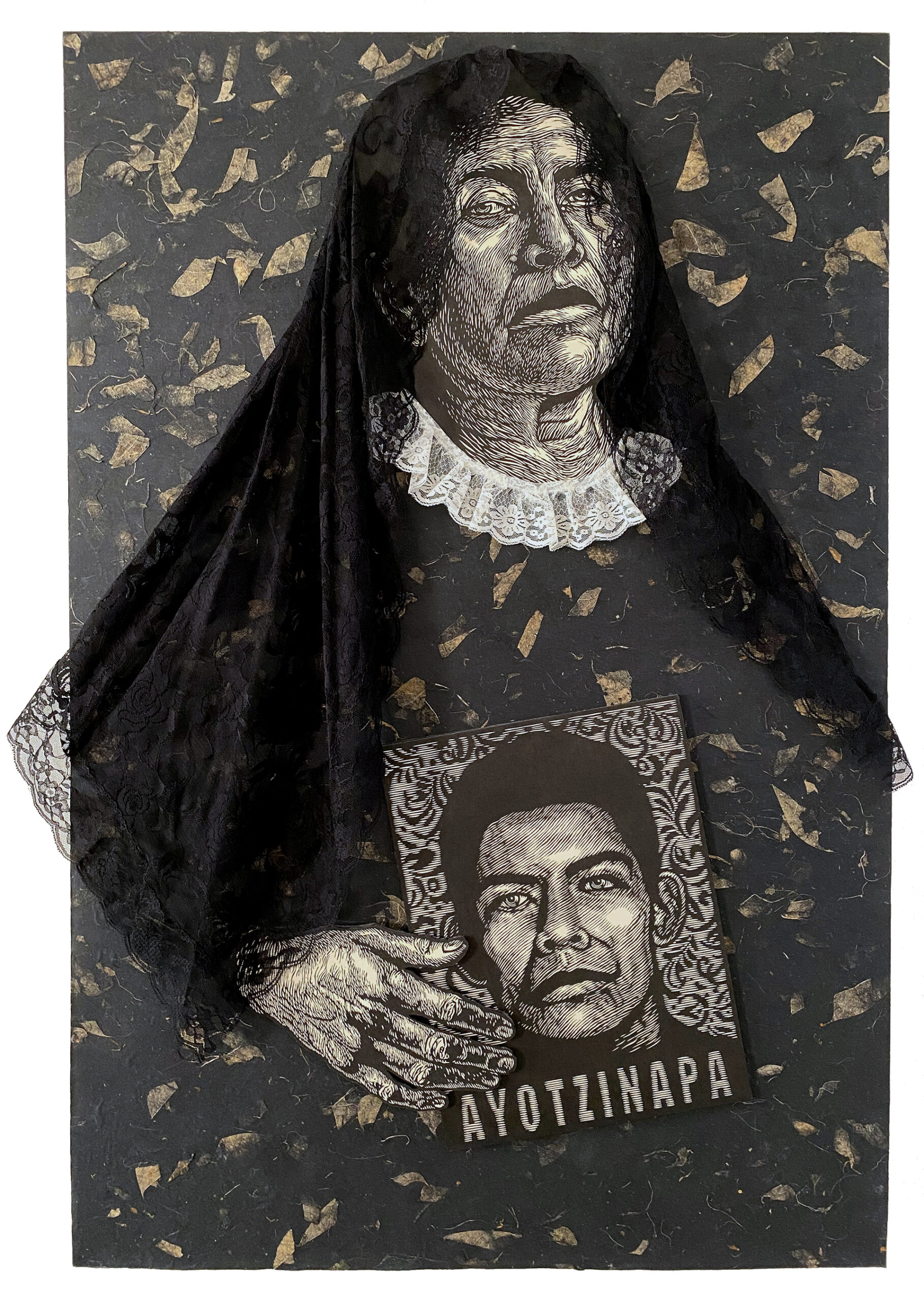

Madre de Ayotzinapa

Linocut and mixed media on wood panel

36” x 24”

2019

Free Them All

Linocut

24” x 18”

2024