Interview

Gino Castellanos: Into the Wild

“Into the Wild” is a regular interview with early career print artists. Interviews will highlight the varied paths the subjects are taking to strike an accord between life and their artistic practice. Expect a balance of approaches, from those hopping the residency circuit, to those teaching part-time or who snagged the elusive tenure-track gig right out of the gate, or those working a desk job or waiting tables to afford access to a community print shop or maker space. In short, there’s many ways to “make it” and we want to share them all!

Have an idea for a person to interview? Please submit suggestions to the Interviews section of the Submissions portal below.

Gino Castellanos

Gino Castellanos is a Cuban printmaker and graphic designer who obtained his bachelor’s degree in Graphic Design from Florida Atlantic University in 2020. He’s currently a freelance designer and artist based in South Florida, USA. Gino obtained his MFA in Studio art with emphasis in printmaking from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 2024.

Gino’s first 16 years of life were spent on the island of Cuba, where he was raised and lived in a different culture. When arriving in America in 2011, he understood that the only way forward was with diligence and discipline, which he used to focus on his education and career. Since beginning his career as an artist, Gino has been in over 60 group and selected exhibitions around the U.S, 2 solo exhibitions, and has been engaged in service with his communities as well as several academic institutions. Major awards include the Emerging Printmaker Award from Southern Graphics Council International. He’s currently teaching at Florida Atlantic University and Palm Beach State College.

Artist Statement:

As a contemporary artist, my work delves into the interplay between human hardship and hope, exploring their profound influence on humanity both spiritually and historically. By employing symbolism and interpreting history through the lens of Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious and cultural behavioral patterns, my work seeks to create universally resonant images that bridge the gap between our current selves and our ancestral past. In this intersection, I hope to uncover insights into the complexities of the human experience.

My art transcends individual narratives to address universal themes. It is not merely a reflection of my own memories and identity but an exploration of the shared human condition. My intention is to harmonize emotion and intellect, emphasizing our spiritual connections while remaining attuned to contemporary sensibilities.

My curiosity about the nature of reality drives my artistic practice. I have a deep desire to go beyond the surface of my work to engage the viewer’s imagination—and ultimately, their heart.

The Interview

Blake Sanders: You were born and raised in Cuba, then immigrated as a teenager, a time of life already full of big changes. What was your experience as you adapted–or not!–to life in the States? How did that turbulent period set the groundwork for your mindset and career? How does your identity as a Cuban continue to influence your experiences?

Gino Castellanos: The process of adapting to American society is something I’m still undergoing—and something I expect will continue for the rest of my life. To understand this, one must consider not only where I come from but also where I arrived. Both countries have long, complicated

histories, and their lifestyles could not be more different.

Because of censorship and propaganda in Cuba, I spent the first 16 years of my life cut off from the outside world. Cuba wasn’t just my country—it was my entire universe. Migrating felt like dying and being reborn in a new body. Even now, I sometimes have sudden flashbacks of my childhood, and they feel more like glimpses of a past life than memories of my own. It’s strange. I often feel like I only began living at 16—and that’s a difficult age to be born into. Imagine being thrust into existence during the most awkward stage of adolescence. It messes with you.

Navigating a public high school in South Florida was rough, to say the least. Clashing with the average American teenager left me alienated, confused, and struggling with my first real experience of depression at a vulnerable age.

Still, I thank God every day that I wasn’t born in the U.S., just as much as I thank Him for not letting me stay in Cuba. The timing of my immigration shaped me in exactly the way I needed. It gave me a perspective few others have. In an age obsessed with online image and performative suffering, I know what real hardship looks and feels like. If you pay close attention, that experience is embedded in everything I make. The deep gratitude I feel for the life I’ve lived drives me to create with urgency and purpose.

My identity influences my work by reminding me to celebrate the human condition—to recognize pain and beauty together—and to take responsibility for my life without casting blame on others for my misfortunes. That, to me, is the heart of what it means to live honestly.

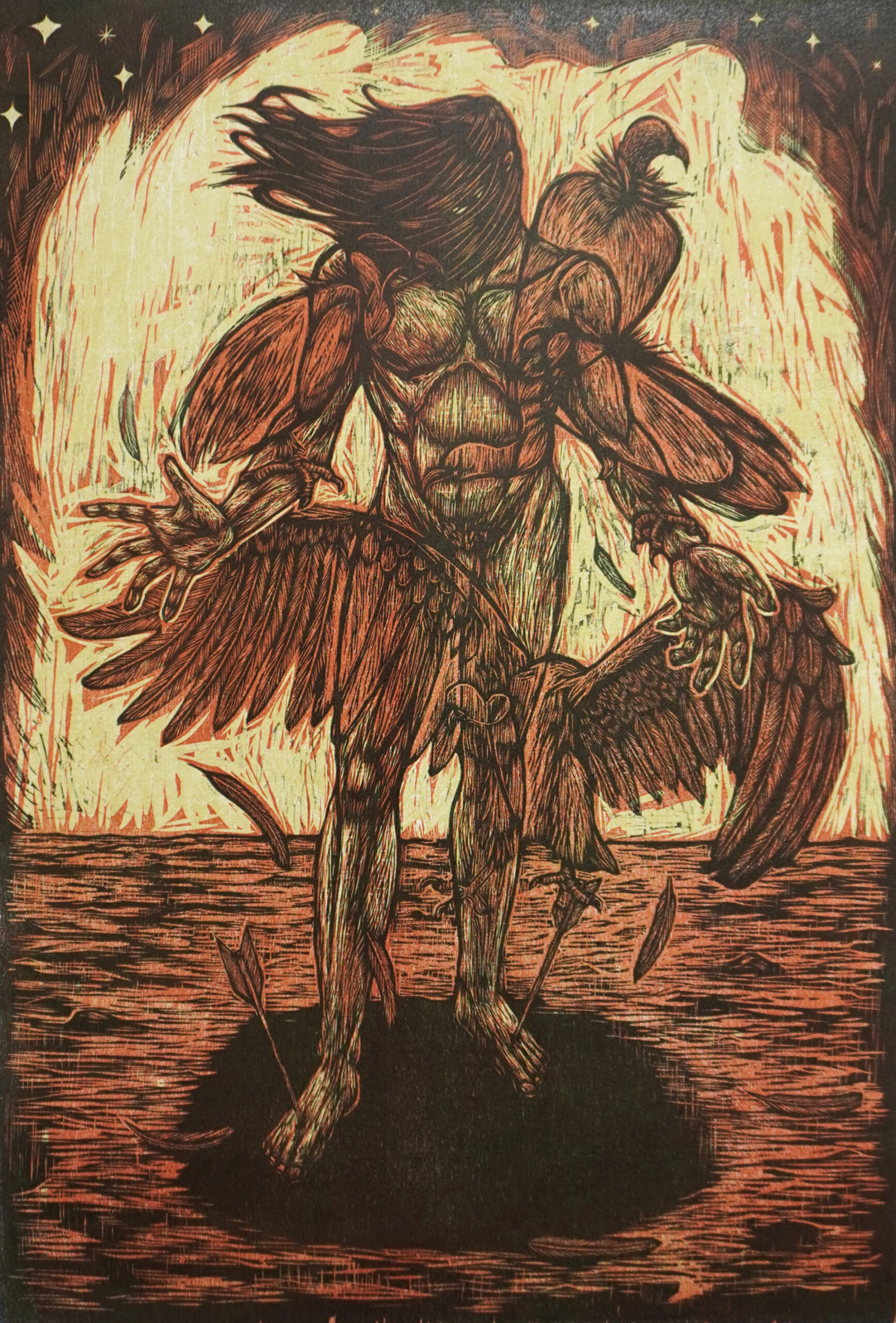

I’ve Been Here All Along

Woodcut

23.5″ x 23″

2024

BS: When did art start to assert itself as an important part of your life? How did the culture and aesthetics of Cuba influence your perspectives and what you made? How did those preferences and approaches change as you spent high school and beyond in the US?

GC: I used to believe that I discovered art randomly in college—but now I realize that’s not true. Art has been with me from the beginning. I’ve always had an overactive imagination, almost to the point of it being burdensome. As a child, I constantly talked to myself, played with sticks, and imagined entire worlds, characters, and storylines in my head. I still do this as an adult—just not as openly, ha. The things I explored in my mind were often strange and wonderful, and I would get lost in them, drifting off in thought during conversations or school lectures. What I lacked back then was the patience to develop a skill—like drawing or painting—that would allow me to express this inner world.

In Cuba, I paid little attention to art in a conscious way. Whatever I absorbed, I absorbed passively. I remember getting lost in paintings as a kid, but I didn’t think of them as things made by people. They just existed, like clouds or mountains—things to observe, not create.

When I started making prints in America, I mistakenly thought I had to dig into my culture to find inspiration. So I did. I looked to Cuban culture and Cuban art in an effort to find myself through it. But nothing clicked. It was my past—and it no longer served my future. In grad school, I finally realized I wasn’t meant to make work about a culture. I needed to make work about everything and everyone. That was the only thing that felt honest.

If it sounds like there’s some distance between me and my culture, it’s because there is. Our relationship is complicated.

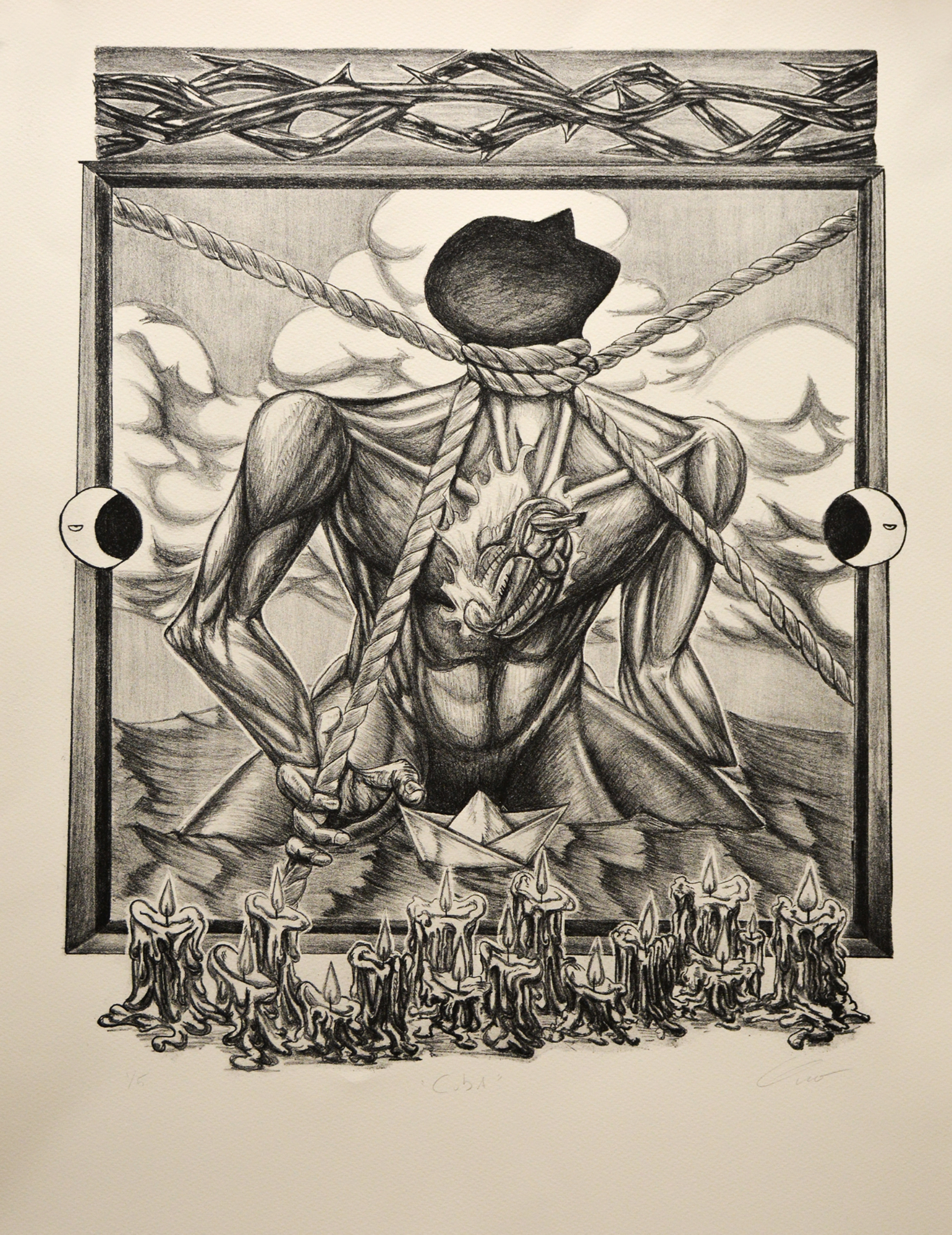

Cuba

Lithograph

24″ x 19″

2024

BS: You attended Florida Atlantic University where you studied with Joseph Velasquez. How did FAU, and the printmaking culture specifically, influence the direction of your work?

GC: I ended up in Joseph’s printmaking class by accident. I was a graphic design major and had signed up for the class thinking it was screen printing. It turned out to be woodcut. I stuck with it, partly because I liked Joseph. He struck me as a no-nonsense kind of guy—someone who expected hard work and had no patience for excuses. It was refreshing to work under someone like that. For some reason, the whole class wanted to make him proud. I definitely did. I wanted to create a piece he’d look at and simply say, “That’s good.”

Looking back, I think I was drawn to him because I was searching for a mentor—someone who could help me develop a skill and take it seriously. Joseph filled that role in a way no one else ever had, in any part of my life. His class felt like an opportunity to become good at something for the first time. Until then, I’d been pretty aimless, with no real skill in anything worthwhile.

There’s something rose-tinted about undergrad—it’s a relatively carefree time, which made it easy to be enchanted by the environment. At FAU, I met a few classmates who were passionate about doing good work, and that energy rubbed off on me. I realized I could express some of the things I was quietly worrying about and turn them into interesting pieces of art. So even after the semester ended, I stuck around. I couldn’t take more printmaking classes, but I joined the print club and kept asking questions.

To be honest, I don’t think Joseph liked me at first. He was pretty dismissive. But I kept showing up, and eventually he warmed up to me. Over time, he taught me a lot—not just technique, but discipline. I see him as a father figure now, someone I deeply respect. Our artistic styles and philosophies couldn’t be more different, but he was a huge influence on my career. It’s no exaggeration to say that without him, I wouldn’t have had the desire or the stamina to make it this far.

I should also mention that around that time, I started feeling disillusioned with graphic design. It was all about copying trends, pleasing clients, and chasing surface-level aesthetics. Ironically, I’d later realize how similar that is to the art world—but at the time, printmaking felt like something different, something more honest. And I wanted to pursue it.

Dos

Woodcut

21″ x 28″

2024

BS: After FAU you got your MFA at UT Knoxville. Did you experience any contrast between living and studying in Tennessee vs. South Florida? How did the mentorship and camaraderie of that program alter your path?

GC: Knoxville is where I came of age as an artist. It was a very different experience from undergrad—more challenging, more isolating, but ultimately necessary. I’m grateful I went through it when I did, because it opened my eyes to the reality of academia and shaped me into a stronger artist. That said, looking back, I realize I wasn’t ready for the program. I entered grad school simply because it felt like the next logical step. I didn’t yet understand enough about art, printmaking, academia, or the structure of graduate education. It felt like I had been thrown into the deep end without knowing how to swim.

While I valued my time with mentors and peers, it wasn’t always sunshine and rainbows. There’s a certain awkwardness in the social fabric of graduate art programs—a kind of artsy performativity that I struggled to connect with. Because of that, I turned inward and focused on the work. Maybe that made me seem distant, but it was a necessary form of self-preservation. In some ways, the experience reminded me of immigrating to the U.S.—being in a world that looked familiar on the surface, but feeling entirely out of place beneath it. Just not at home.

By the end of the program, I learned to take what I needed from my mentors and peers, and to let the rest go. That helped me come out of the experience without losing myself. If I had to describe grad school in two words, they’d be: not real. That’s not meant as a criticism of UTK specifically, but of graduate art programs more broadly. They don’t reflect real life, real art-making, or real relationships. It’s three years inside an academic bubble, where you’re encouraged to produce but not always prepared for what comes after.

Some people leave grad school refreshed and wiser. Others leave disoriented and a little broken. I think most people experience a mix of both. It all depends on the perspective you carry with you when you step outside that bubble.

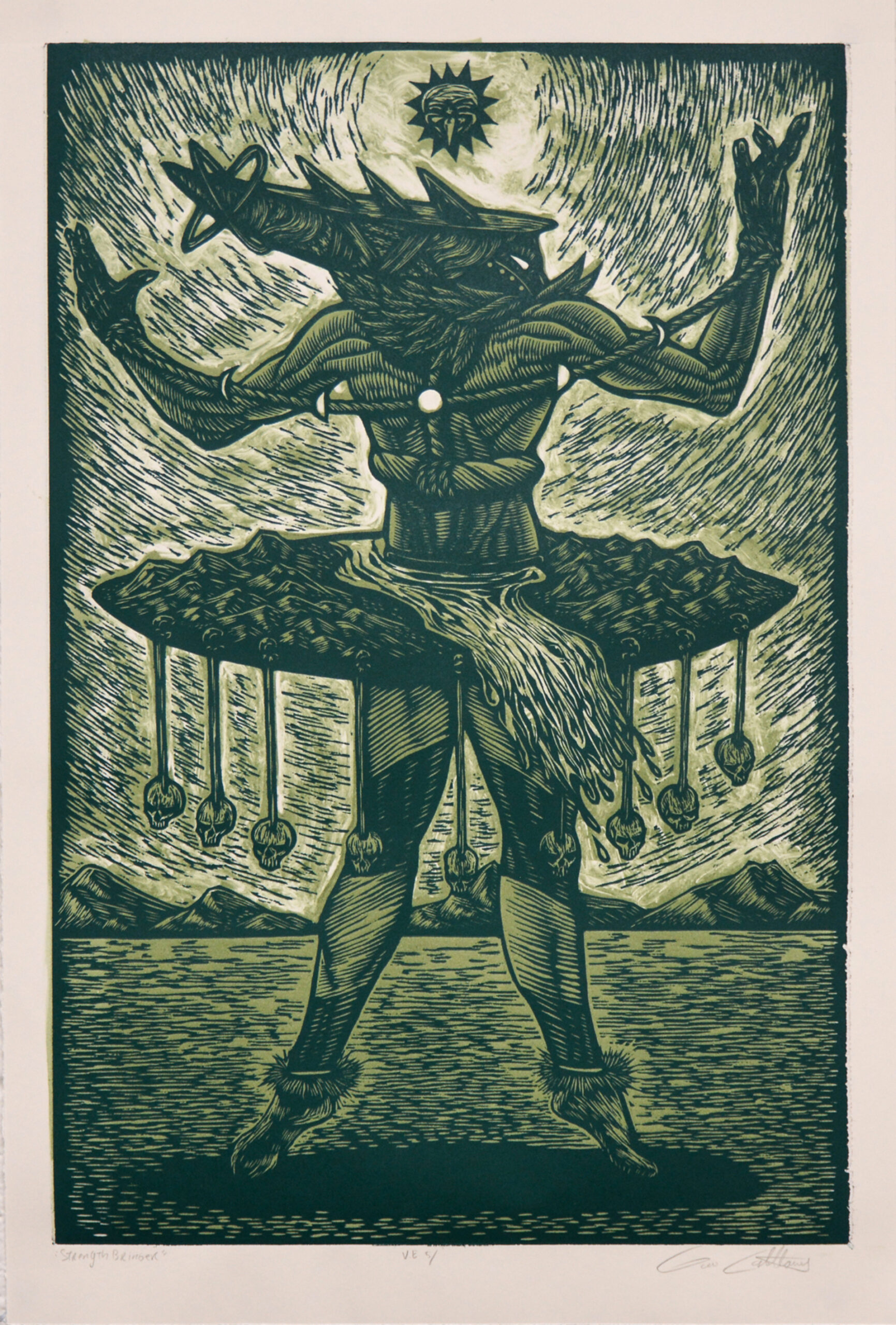

Strengthbringer

Woodcut and Monotype

24″ x 19″

2022

King of Nothing

Woodcut

26″ x 19″

2025

BS: Your printmaking portfolio is filled with figurative work that conveys spirituality through symbolism and drama. The work often alludes to mythologies and graphic traditions from many cultures. How did the ingredients of these varied influences come together to produce the recipe that became your oeuvre? How do you employ these references while avoiding appropriation?

GC: It’s hard to answer this question without pissing people off. I have a somewhat controversial opinion: I don’t believe in cultural appropriation. I don’t think culture belongs to anyone. It’s not property. You can’t buy it or earn it. You’re either a culture creator or a culture preserver. That’s it.

If you reference a culture in your work—whether you were born into it or not—you’re participating in that culture’s preservation or evolution. If you falsely claim to be from a culture you’re not part of, it’ll show. It’ll come off as dishonest, foolish and disconnected, and people will see through it. But even then, you’re not really harming the culture itself. Wearing a costume doesn’t make you the thing you’re pretending to be. Pretending doesn’t equal participation.

You can critique cultures. And I’d argue that you should, if it comes from a place of honesty. That’s how cultures stay alive—through conversation, criticism, reinvention. No culture is above criticism. If you’re part of this world, you have the responsibility to speak on what you see. The only requirement is that it’s your own voice, not someone else’s talking points.

My work leans into mythology because the world is starving for it. People are desperate for meaning, for the hero’s journey, for archetypes that help them make sense of the roles we’re all called to play. In the postmodern era, where everything can mean anything, nothing means anything. That’s why so many people feel lost.

I borrow from ancient stories that keep resurfacing across time and cultures—because they’re true. These myths are timeless. The figures in my work are both ancient and modern. They belong to old cultures and future ones. In that sense, my work draws from everywhere and speaks to everyone. That, to me, is how you make something original. That’s what makes someone a culture creator. It’s not just my style—it’s my responsibility, both as an artist and as a citizen of the world.

This has always been a point of contention between me and my mentors. I’ve often been told to make art about my Cuban identity or to engage more directly with social issues. But to me, that’s limiting. It turns the work inward when it should be reaching outward. I’d rather speak directly to your heart, because your brain is already overwhelmed trying to decide what to believe in an age of endless noise.

Moriras

Woodcut

27″ x 18″

2023

Pilgrim

Woodcut

26″ x 37″

2023

BS: You’ve shown a lot in a relatively short career. Would you please share how you’ve parlayed connections and pursued opportunities and how that has built momentum?

GC: I’m not sure I’m the best person to ask about making connections or pursuing opportunities—because, truthfully, I haven’t done much of that in the traditional sense.

In grad school, I was told to network as much as possible: to make friends, to be liked, to get out there and hustle. But that idea always gave me a strange sense of dread. I didn’t want to strategize my way into recognition. I didn’t want to receive opportunities just because people liked me or thought I was charming. I wanted to be offered opportunities because the work stood on its own. Because it was good. That’s all I ever wanted—to make decent work and have it be enough. I believed in merit. I still do, though maybe I shouldn’t.

Most of the connections I’ve made have happened naturally. I try to be myself, within reason, and let people come to their own conclusions. The ones who resonate with me usually stick around; the ones who don’t tend to keep their distance. If I’m genuinely interested in someone, I’ll reach out—online, in person, whatever makes sense. If I want to visit a print shop or apply to a residency, I’ll do it. But I don’t force things just to pad a CV. That mindset doesn’t help the work, and it doesn’t help my sense of professionalism either.

I’ve stopped thinking I have something to prove. That might not be great advice, but it’s the truth. If I said anything else I would be dishonest.

Show Yourself

Woodcut

13.5″ x 13″

2025

BS: In your bio you describe yourself currently as a freelance designer first. What prompted this shift from print to design? Do you see these disciplines as distinct? How does print influence your design work and vice versa?

GC: To be honest, it says designer first because it tends to be overlooked when people see my website or talk to me. I place it first as a reminder that it’s something I still do and can make me money. But at heart I am a printmaker first, designer second.

I went into print to escape the design world, but found out their communities are very similar. In the end, what kind of designer or artist you are depends fully on yourself, and not the people making alongside you. Printmaking and Design are both deeply connected. Their history is so similar that it’s

hard to talk about one without mentioning the other. But the way I work places them distinctly apart. I make designs with geometrical precision, and my art is purposely messy looking and the opposite of precise. With the design I feel trapped and orderly, with art I am free.

Tension

Woodcut

34″ x 50″

2025

BS: You’re teaching at FAU and Palm Beach State College. Do you see higher education as the path you’ll continue to follow going forward? What are your current goals going forward? How does teaching inform your practice, for better or worse?

GC: I would love to answer with a definitive answer, but the truth is that I don’t know. Right now I am enjoying teaching and seeing the growth of other people first hand. I think it is a very rewarding job. Having said that, I have my issues with academia, which I will spare you. There are things about the educational system that worry me a bit. All I can say is that I haven’t made up my mind yet. As for right now, my main focus is to continue making, and to take care of my family’s best interest. As long as I am teaching, I will do the best job I can.

As to how teaching informs my practice, I would say that it allows me to put some of my ideas and philosophies to the test. I started out teaching by the book, but every semester I have been changing things around and making the classes more my style, while I pay attention to student outcomes. I’ve noticed that the more I change things up, the more the students respond with their best work. Having the ability to test this is invaluable for me at the moment. That, and seeing how the students show genuine appreciation for what I do makes me want to work even harder.

The Immigrant

12.5″ x 12″

2024

BS: What advice would you give current students as they’re about to journey into the wild? What do you wish you’d been told or prepared for?

GC: I struggle with giving advice since I’m still at the beginning of my career—but if I think about the things I wish I had known earlier, here’s what comes to mind:

First, art is not schematic. No one can tell you how or why to make art. No book, no conversation, no mentor can give you a blueprint. If a professor or friend ever tells you, “You should try this,” pause and ask yourself—honestly—whether that person truly understands your interests, and whether their advice is right for you. If it’s not, you can ignore them. Even if it’s your favorite professor, your best friend, or your mom. This also applies to prompts: if a professor asks you to make work about something you don’t care about, do something else. It’s better to make them angry than to waste your time. If they do get angry, that might be a sign that they don’t actually value your individuality—which is their problem, not yours.

Read what you want to read. Don’t feel obligated to follow anyone’s reading list. You’re building your own mind, not borrowing someone else’s.

Avoid political rhetoric. It’s divisive, limiting, and often turns artists into parrots. You can’t fix the world if you haven’t figured yourself out first. Focus on your own development. Be useful, be responsible. Then talk.

As an artist, your job is to show what beauty can do to the soul. Pursue beauty. Some radical professors will say beauty is subjective or irrelevant. That’s not true. Beauty is real, and you know it when you see it. Chase beauty, and you’ll be chasing the truth.

Don’t get obsessed with process. A 25-layer lithograph doesn’t make a piece good. Ask yourself: is the image strong, or isn’t it? Process won’t save a bad image.

Don’t hang out with people you don’t like. It’s never worth it in the long run. Find people who want you to succeed. Stay true to your principles. If that means your circle is small, let it be small.

Critiques are not as important as people make them out to be. They’re often theatrical. You’ll get more honest reactions in one-on-one conversations or studio visits.

Understand that your job is not just to make pretty pictures. Artists have a huge responsibility. No, I don’t mean a “social change” or “social justice” kind of responsibility. I mean a real, powerful, profound one. You are the one in charge of interpreting the zeitgeist. Feel what’s in the air. See if you can translate it into actual tangible somethings.

And finally—work hard and try your best. Not for approval, but so you can live with no regrets.