Interview

Riso-lve: A conversation with Josh Dannin

Josh Dannin is an artist and printmaker originally from Philadelphia, now based in Bethlehem, New Hampshire. Primarily utilizing relief and risograph print processes, his work explores the intersection of mass production, traditional craft, and modern technology. Previously a regular contributor to Printeresting.org, he coedits Power Washer Zine, a semiannual publication about screenprinting featuring artist interviews and essays, high-end humor, and lo-fi graphics. In addition to leading workshops at Directangle Press, Dannin teaches printmaking as a Visiting Lecturer at Dartmouth College.

Dannin’s printed and bound works have been exhibited nationally and internationally at galleries, artist-run spaces, and museums including International Print Center New York (Chelsea), Anderson Ranch Arts Center (Snowmass Village, Colo.), Rochester Museum of Fine Arts (Rochester, N.H.), Vitebsk Center of Contemporary Art (Vitebsk, Belarus), Cork Printmakers (Cork, Ireland), and Fondazione Il Bisonte (Florence, Italy). He has worked as an artist-in-residence in studios including Cork Printmakers (Cork, Ireland), Atelier Presse Papier (Trois-Rivières, QC, Canada), Spark Box Studio (Picton, ON, Canada), and Honolulu Printmakers (Honolulu, HI).

The Interview

This interview is composed of a Zoom conversation edited lightly for clarity and flow, and supplemented with a couple parenthetical explanations about risography.

Blake Sanders: Hi, Josh. Do you mind telling us a little bit about who you are and what your title is?

Josh Dannin: Yeah, so my name is Josh. I’m a printmaker and I guess studio proprietor, director, wear many hats here at Directangle Press up in northern New Hampshire in Bethlehem which is in the White Mountains. I also teach a bit about an hour south at Dartmouth, one term a year. And I co-edit a publication called Power Washer Zine with some of my good friends, Todd Irwin and Jon Irving. I think that is most of things!

BS: That’s exactly why I wanted you to introduce yourself because I knew there was a lot and I didn’t know exactly what your nomenclature was.

Let’s get into this! Directangle began as a publishing imprint while you were in graduate school at Ohio University. What inspired you to take the role of collaborative printer and publisher? And having gone through a grad program, how did you find the time?

JD: I was in grad school at Ohio University from 2012 to 2015. I had a really great group of folks as fellow students in the program, super interdisciplinary, even though we were very much in the printmaking area, there were people doing all kinds of great stuff. Great faculty, Melissa Haviland, Karla Hackenmiller, Art Werger, and Mary Manusos were my crew when I was there. What got me thinking about starting something more formally as a publishing imprint or a means of formally doing collaborative edition work was the beginning of my second year of grad school out of the three-year program Melissa Haviland and I worked together to get a visiting artist program at OU printmaking moving again. One of the first people we brought in was Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. Amos had long been somebody I really admired and looked up to both as a maker, and as an incredible person, organizer, speaker, you know, all of the above. We were fortunate to bring him in and he worked with us for a week in 2014 and we worked with the community and worked with people around the School of Art.

I had already started amassing my own horde of equipment because we didn’t have letterpress equipment when I was an undergrad and I got into it towards the end. So when Amos came to OU, we ended up setting up a pop-up shop for him to utilize during his visit all made up of my presses and nonsense that I had stored on campus so that got the ball rolling, gave me a reason to have my stuff, my equipment, personal equipment organized and started this great relationship I’ve developed with Amos since then. Amos was the first person I ever worked with on a formal collaboration, later that same year Fall of 2014.

I really enjoyed working with Amos and other visiting artists we brought in while in grad school. Everybody involved in the program would have the opportunity to work together on these editions that we would produce when artists came through. I think a lot of folks have had that experience while in school and it’s like the greatest thing in the world. It’s an expansion on the community that’s already there and exciting and great. You learn so many things from seeing how other people work and different approaches to making. You learn conceptual things that you may not have otherwise heard of as people are producing their work or treating the press like a painting tool as Amos does, all these cool things. So kind of a combination of that and also being in a position where I had already kind of found a bunch of equipment in various states that I had been working on.

By the time I got to my third year at OU, which was an open thesis year for all intents and purposes, I had my own equipment in my studio. I kept the ball rolling with this relationship with Amos and started working on some stuff with my studio mate in grad school, Todd Irwin.

We were editioning stuff and then it went from there. A combination of equipment access and the visiting artist program allowed the press to start organically in grad school. I was really interested in figuring out how to continue working with people in a community and collaborative way after school ended. In my case, I didn’t have to seek out the equipment because I already had stuff, so I wasn’t necessarily going to be working in a community shop. One, I don’t think I could have afforded to be a member of a community shop at that point. I also had the potential to work as an independent operation in some very early sense. I was thinking about how I can continue working with people and making cool stuff and it just seemed like a great way to do it.

Past resident Keith S. Wilson and the mighty Vandercook Universal III

2024

Web: keithswilson.com

IG: @keithing_it_real

BS: Directangle then moved on to Pittsburgh and then to Goffstown, New Hampshire before settling in your really gorgeous location in New Hampshire. How did the imprint and the shop evolve in those various locations?

JD: As I was finishing up grad school I had linked up with some folks in Pittsburgh. There was this really great community of people in various areas of the School of Art and theater and film as well, I believe, that had gone from Ohio University to this neighborhood on the east side of Pittsburgh, Wilkinsburg. Some friends had opened up a studio space there and invited me to join them. They had a side room and they offered me some space to move my shop in exchange for working with them a little bit in their space. And they had a linotype set up. It was really cool. I learned how to use the linotype and cast lines of hot lead and stuff like that. It was a really great way to continue that kind of community environment because there were a bunch of people that I had either direct ties to through grad school or were friends of friends that became my friends and stuff like that.

I moved my shop to Pittsburgh in May of 2015. A few months prior to that I found myself in possession of a Riso printer, a GR3750 that I purchased from my friend Sage Perrott and Adam Leestma since they were moving across the country and had to figure out what of their own hoard of equipment they could take with them to Utah from West Virginia where they were living. I was just about to start working on this Power Washer publication with my buddy Todd Irwin so it seemed like the perfect reason to try to figure out what the hell a Risograph was.

At the time there were like not that many of them floating around the States. Some people were already crushing it and doing really amazing things. I relied on a Google group and Copytechnet, this really interesting old forum. So I ended up with this Riso printer almost by accident. I happened upon possession of this thing which evolved the shop in a lot of ways before I even really knew how to use the machine.

Pretty quickly people in Pittsburgh found out that I had it, and then started asking me to print for them. I thought, well, I can’t say no because I need work, but also I don’t know how to use this well yet and I don’t even know if it works well. That was the thing that really started evolving the trajectory of the studio from being a publishing imprint doing collaborative projects, to starting to unintentionally move into contract printing for other artists and offering more of a service. That started in Pittsburgh.

Fast forward a few months, I got an opportunity to move up to Manchester, New Hampshire as an artist in residence at St. Anselm College. They offered me a studio space and a part-time technician gig. I had an opportunity to not have to pay for a studio and start working in an academic setting with very few additional responsibilities and be able to bring in some money. So I moved my shop up there. From early 2016 to early 2018, I had my studio on campus. Since my studio was on campus, I wasn’t bringng in artists. I didn’t feel like I could bring random people onto campus into the buildings. I was doing a lot more printing for other people accidentally. A lot of this stuff felt like accidental things that were happening. I would end up printing this or that thing. Stuff developed into doing some more collaborative projects, but I was also starting to print a lot for other people and doing some artist book stuff in the process. I eventually ended up teaching at that school, St. Anselm College, in a faculty/staff hybrid, full-time for three years. Then at a certain point I was ready to move my shop off campus back into a brick and mortar space like I had started doing with Pittsburgh.

I found a little storefront in the neighboring town of Goffstown, which was more like a Gilmore Girls style village right outside of Manchester. I set up shop there and started running Riso workshops monthly and continued to print for other people and do collaborative work.

Going back to your question, the evolution was brought on by a combination of environmental changes and studio capacity capabilities. When I was in Pittsburgh, I only had my letterpress stuff in my little wedge shaped shop and in my first phase in New Hampshire, I couldn’t have guests in the studio formally. When I got to my next brick and mortar space in Goffstown, it was the first time I had letterpress stuff set up, which with carving based work remains my passion, and Riso stuff in the same space. All of a sudden it was publicly facing and I could just kind of do whatever I wanted on a pretty cheap tab. Part of it was survival. When I was on campus with my studio I was always on campus, even if I was there making my own work and trying to hide away. I was also there as a technician sometimes or when I was teaching full time, students would be in there at 10 o’clock trying to finish their project and I’d be hiding behind a door two doors down trying to work on my own stuff. If someone knocks on the door, I couldn’t say no so I needed at some point to kind of figure out that separation everyone in academia in one way or another can relate to.

I spent a few years hoping that something could work in a different way when I had a boatload of stuff stored in closets in a few different cities and garages, so then I decided it was time to funnel it into one space.

In-studio bindery day with Bread & Puppet crew for second edition of I AM YOU.

2023

BS: You were talking about how when you first got the Riso, you were really learning on the job. You didn’t know what you were doing with your machine. You weren’t even sure it was any good. I’m having a similar experience with the Riso I have access to, it’s a little bit clunky. We’ve got limited colors. I’m finding my way around the machine. Can you talk about that journey for you and how your Rizzo component of the shop grew? You have a prodigious color selection now, for example. How much of that was your interest growing and how much of that growth was a necessity as a contract printer?

JD: During the time that I was still operating behind closed doors on campus at that school Riso was still not quite familiar across the printmaking and design community, but it was definitely popping up. There were people that had been doing it for years prior but I remember a specific point, I think at a book fair at the beginning of 2018, I want to say it was, that people would come up to my table and ask, what is this stuff? How is this made? Then later that year, maybe eight months go by and people are like, where are you getting your riso prints done?

I feel like there was this very quick thing, based on my particular experience. During this time I was printing things that came my way, I just let it happen organically. It was really when I moved my studio back off campus there was all of a sudden a different overhead to factor in that I had to think about the finances differently, and I was also working on taking the leap to step out of academia as my main source of income and switch the scales to being from predominantly academic income with some studio income to try to like switch that.

That coincided with riso becoming more and more prominent in the community. As I was working through my equipment, I became more in tune with how to do what and try to make it behave in whatever way I could. This has been an ongoing battle, something I’ve come to terms with in different ways over the years. I always tell people that if you’re going to get into Riso printing you need a good therapist as a counterpart to your machine. Anybody that’s working with piece of equipment that is the thing they’re always in front of for long enough, you figure out its personality. I ended up with two machines at one point, mostly so I had a backup machine for parts. That one, which was the same thing, had a different personality than the one I was printing with primarily. Through working on stuff and tinkering you figure out what’s what.

Especially early on there’s a massive community element where people are hopping on Skype to commiserate and help each other out. I used to hop on Skype with Tate Foley in St. Louis and we both had the same machine.We’d open the back of our machines and be looking at the screens side by side and be like, oh, your machine’s blinking in that spot, but this one isn’t and try to figure out what that meant.I learned a lot just through printing for other people. I would do stuff of my own just to learn what I could get away with and learn the tolerances and try to figure out what I could dial in, all this time wishing it was a Vandercook that I could adjust a physical gear on! Then figuring out what I could do to make myself have a greater sense of control, to try to do what I understood as edition printing, even though it was a Riso [which is inherently somewhat inconsistent], so it was kind of a conundrum.

Through printing more and then having to figure out the financial side I started taking on more projects. We started running workshops in the studio, which gave me another way to bring a different audience into the shop. Then those people that would come do introductory workshops were eligible to come back and rent studio time and work on the presses. Everyone was interested in riso and while I had letterpress equipment–which I was using for myself and other people–riso seemed like a better thing to try to accomplish in a three-hour workshop. I could teach people the ins and outs and the fundamentals of working computer free in a collage based manner with the Riso and people could leave with some knowledge and some cool prints and some new friends. Then maybe come back. That happened pretty steadily from opening that space in fall of 2018 until everything shut down in 2020. There was a pretty steady stream of people coming through from all over New England. It was kind of wild, they’d come to this tiny town I didn’t know about prior to moving to. The Riso, even though that was by no means where I came from, became this central fixture. Through that, I learned more stuff that I could do. I cleaned up additional color drums that I had sitting around. I ended up with 19 drums! [Each drum holds one color ink. You load a drum for each color run of an edition. The more drums you have the more color flexibility you have because it’s laborious to switch the colors in a drum.]

At one point I started having trouble with one of those machines and I had a lot of projects piling up and I had to make the decision to make an investment into something that was like more reliable and better behaved so I sold a bunch of my Riso equipment and started from the ground up again with new to me two color printers. Then that was a big scare. That was the first time I spent money on what I was doing.

POWER WASHER ZINE is Todd Irwin, Josh Dannin, and Jon Irving.

Promotional photo for Power Washer Zine Presents: POWER WASHER ZINE’S REAL-TIME ZINE JAMBOREE at STUDIO TWO THREE, a participatory printmaking event while in residence at Studio Two Three, Richmond, Virginia. 2025

Web: powerwasherzine.com

IG: @powerwasherzine

BS: Do you have any advice for somebody who is interested in Riso and wants to start a shop? What machine do you think is a good way to jump in? What colors do you think are essential to have in your arsenal? What paper to you start with?

JD: Oh, man. Well, I should start by saying that I am no authority. There are people that I talked to early on when I was getting started. I met this great guy, Matt Davis, who runs Perfectly Acceptable Press in Chicago, really early on who at the time was running a space at Spudnik Press in Chicago. I was in there because one of my friends was there and we got chatting. That meeting becomes my first Riso contact because he introduced me to the Church of Risology, the Google group, which put me in touch with these other people troubleshooting things, and it all spiraled from there.

Things were different when I was getting my machines because you could still get–you could not get parts–but you could still get ink for the older GR Riso printers that I started out using. They’re still out there. Tons of people have them and there are ways to keep them going. With the ink you have to manually transition ink from one tube to the next. Or someone had developed a 3D printed component that would allow newer ink tubes to fit into those machines. This is super boring! If anybody has interest in that stuff, there’s all kinds of resources online now, but I’m happy to chat more about it.

At this point there are some great resources out there that have given artists access to knowledge. Instead of taking a risk on a random machine on Craigslist, you can call up Halligans in Chicago and be like, oh, do you have any machines off lease? There are people that are moving from one kind of setup to the next sometimes and you can get their hand-me-downs. Riso’s gotten very popular though over the past handful of years.

That point I referenced in 2018 where everyone all of a sudden is asking, where’d you get your reset printing? That’s already seven, eight years ago, right? So a lot has happened and the pandemic times also led a lot of people to acquiring their own stuff to be more self-sufficient. So there’s more competition for equipment, too.

What the right machine is depends on a few things: budget, how willing you are to get your hands dirty and like get into surgery mode (and if you like dealing with electronics or gears or plastic gears that break that you might have to 3D print), or if you like sitting around and chatting with people on a Discord. There’s all kinds of ways that you can make something that is maybe a less ideal acquisition on the front end become potentially something that can work really well for you. I think the key word there is potentially because you just don’t know. There’s a lot of stuff out there now that you just don’t know what you’re getting.

I’ve been very lucky that what I ended up with in this stage of my Riso setup is generally pretty well behaved. I honestly feel like part of it is did I eat a good breakfast this morning? That might influence if the machine behaves. Completely random. A lot of this stuff is totally personal preference. I think that there’s a big decision between one color machine versus two color machine.

We just brought in a new to us machine that’s a one color by choice to have it as an option relative to the two colors. I like the two color printers for production when I’m printing for other people for the sake of efficiency. Ultimately though, thinking about it from the printmaking perspective, which is like where I enter all this, I think there’s something to be said for true layer by layer experimentation. If I was getting into it from the get-go and I was just telling a student of mine who was about to start a shop for something of their own, I’d probably say get something computer free, with good resolution, and get colors that you want to use for your work. Get into analog mode and pretend it’s a punk rock copy machine that all of a sudden has translucent layering capabilities. I didn’t have computer input the first four or five years. I was using the setup I was given. I accidentally had a bunch of colors, but I think I personally used like three in my personal work. So that’s a tough question to answer. There are like a million colors now. I guess there always have been, but people are aware of them now is the thing.

Directangle Press studio pre-expansion, Bethlehem, New Hampshire.

2024

BS: You talked a little bit about how things were progressing in Goffstown right up until the pandemic. You moved to your sort of forever home in 2020. What was it like moving and setting up near the beginning of the pandemic? How did the lockdown allow the press to grow and your priorities to shift?

JD: Yeah, there’s a lot of shifting around. A few things happened leading up to that which really influenced where we landed. The short version is throughout the pandemic, I was basically doing job printing and also doing printing for folks at a handful of different schools. They were either running classes where their students were generating designs that I was then printing for them and then sending them back, or there was some publication classes that I worked with at a handful of different schools. A lot of that time was spent with that besides making some of my own work. A lot of it was just printing for anybody that needed printing, which I think a lot of studios did stuff like that.

The thing that led up to that move that made where I landed particularly appealing, was in summer of 2019, We launched the first iteration of our residency program, which was then called the, let me see if I can remember this, the Micro Riso Residency. That was launched in conjunction with hosting Jason Urban and Leslie Mutchler in my then studio that summer and their awesome son Maks. Jason had reached out about doing some printing and they were interested in traveling up to New Hampshire. I don’t even remember how it came about. I can’t remember if he planted the seed in a previous conversation about starting a residency someday or what, but we used their visit to launch the residency in its then form. I had a lot of conversations with them while they were in the studio. They were working in the shop in August 2019 for around three days, which was the framework that I used for the first iteration of the residency.

With their visit, we called them the inaugural residents, then we launched our first call. We hosted Ashley Fuchs of Bozeman, Montana January of 2020 then used Ashley’s visit to launch the next call. At that point, it was a juried residency. We had sponsorship from a regional paper mill, Monadnock paper, and we had jurors look at applicants. I sat in and was interested in watching the conversation but I was listening along as people selected the residents.

I had just stopped teaching full-time, but I still had a teaching calendar to work around. So the plan was to have a resident in the winter during my winter break and then two in the summer.

That January 2020, we invited Olivia Fredricks and Emmett Merrill to be our residents for summer 2020. We all know what happened. Emmett and Olivia ended up coming together in this shop almost exactly three years after they were invited!

The residencies seemed like a really cool way to again build this idea of community and sharing equipment and creating a space where there could be a creative, collaborative energy. Then when everything shut down, I had the opportunity to just think about what, if anything, was going to be able to happen next. None of us knew at that point what the next day would hold.

Prior to that, I ended up spending some time kicking around New Hampshire trying to figure out where I could see myself being next. I’m from Philadelphia originally and weighed the possibility of going back down there because I didn’t love the Manchester area. I had made some good friends, but I knew it wasn’t where I was going to be long term. For those familiar with this part of the country, this area in the White Mountains is about 60 miles south of the Canadian border, about a half hour west of Mount Washington, which is a very eventful weather location in North America and a point of reference to New England. We’re a half hour from the Vermont border. There’s a strip of towns here, St. Johnsbury, Vermont on the west side of this strip, Littleton, New Hampshire, Bethlehem, New Hampshire, Franconia, New Hampshire. The strip is pocketed between some mountain passes, Franconia Notch, Crawford Notch, a big skiing destination, mountain biking destination, camping, hiking, you know, all kinds of stuff.

There’s an amazing community of creative folks here, musicians, theater people, actors, writers, poets. I came up here and was blown away by the environment, of course, and the energy and I met someone that owned a bakery who introduced me to three other people who introduced me to 10 other people. By the time I got here I had already been–via Instagram anyway because it was very much lockdown mode–I’d already been talking to a small village of people among these literal villages. I started looking around up here and ended up finding this property that was then very cheap, because it needed a ton of work. It’s an old boarding house built in the 20s and there was what was being used as a machine shop out back. I saw the house and was like, yeah, yeah, the house, but I saw the shop and was like, that shop could hold a lot of presses!

The house had the bones of what could become a really ideal spot for the residency program that had started, to evolve into what it is now. I somehow was able to magically purchase a property that I never thought in a million years would be possible. It was cheap at that time and I had a couple years of full-time teaching money set aside leading up to that so the stars aligned in a way that it worked out. The house needed a boatload of work and I was willing to get my hands dirty, but that turned into the next couple of years of printing for other people while working on this property and working on the studio gradually.

Eventually, late ‘22, we restarted the residency program once it felt like I could do so in a responsible manner. That was good for all involved, the artists traveling, my immediate community here, there’s all these factors that you’re weighing. From December of 22, let’s see, I don’t know if this count is accurate anymore, 127 artists, minus the three prior to the pandemic, so we’ve had about 124 people since starting back up again. We have two artists here right now, Robin McGuirl and Emily Caddy, they are artist 126 and artist 127 that we’ve hosted.

Directangle Press residency house and studio at the base of Mount Agassiz, Bethlehem,

New Hampshire.

2022

BS: Wow, that is crazy. That’s impressive. Well, now you’re in the process of expanding again so The machine shed hasn’t been enough. What’s this new phase in the build?

JD: The shop was enough for sure, but there was never anywhere to hang a broom is the thing. You need more space to hang a broom, which quickly became 400 square feet. We’re building an expansion right now for two reasons. Part of it is there’s never been any storage in the space. I’m sure you and anybody that reads or tunes into this can relate. It’s very easy for things to pile up in a print shop so we’re building out this expansion. I was able to secure some funding to help this project get off the ground.

The house, we currently have been hosting two artists at a time for the past two years and some change. I run all this with my amazing supportive wife Emily and our house is communal on the first floor. It was originally disconnected side by side. I assume maybe the owner of the boarding house lived on one side and guests occupied the other. One of the first things I did as I was working on this whole project with the residency originally is I connected the downstairs and made it communal, but our upstairs is still separate. So we have one side of the upstairs and then artists have private rooms and a shared artist bathroom up there. We’ve always had a third artist bedroom up there that was just never utilized. It has just been sitting there. Going back to this theme of community, I’ve always liked the idea of being able to host more artists, whether that means collaborative groups or a collaborative duo alongside another individual artist or whatever makeup. I just didn’t feel like there was enough space in the studio and one of the things about setting up shop and being in a set spot for a while is things start to find you. So someone donated an etching press at one point and we’ve just acquired additional stuff. I’m very selective now and grateful for everything that pops up, so part of the expansion is to really allow our equipment to spread out, but also create more workspace that is open workspace that can be utilized. We can have a designated area for bindery tools. I have a Vandercook that is my press that I’m using that will now have a separate space in the corner so I can leave stuff on press for months at a time, which is my slow, semi-efficient way of working. We’re bringing in a third Riso and ultimately we’ll be able to host up to three people at a time now if and when we decide to do so.

My deadline for finishing this is May 4th. So I’m hopefully going to start painting the end of this week. It looks like a bunch of rough drywall, but it’s close. Then the other thing is up to this point, we haven’t gone back to really hosting a steady calendar of community open programming. Right before the pandemic we started what was called Second Sundays Art/Work, that was an open studio gathering where people could come and just hang out for a couple hours and draw or write or edit photos, knit, do whatever and we would have a featured artist or a featured writer or poet every week that would share every month some of what they were working on. That started to get some legs and get some regular attendees and then everything shut down. So my hope is that with this additional space–we’re also only like eight minute walk from the main street in the center of town here–I’m hoping that we can start welcoming community into this iteration of the shop with the new space.

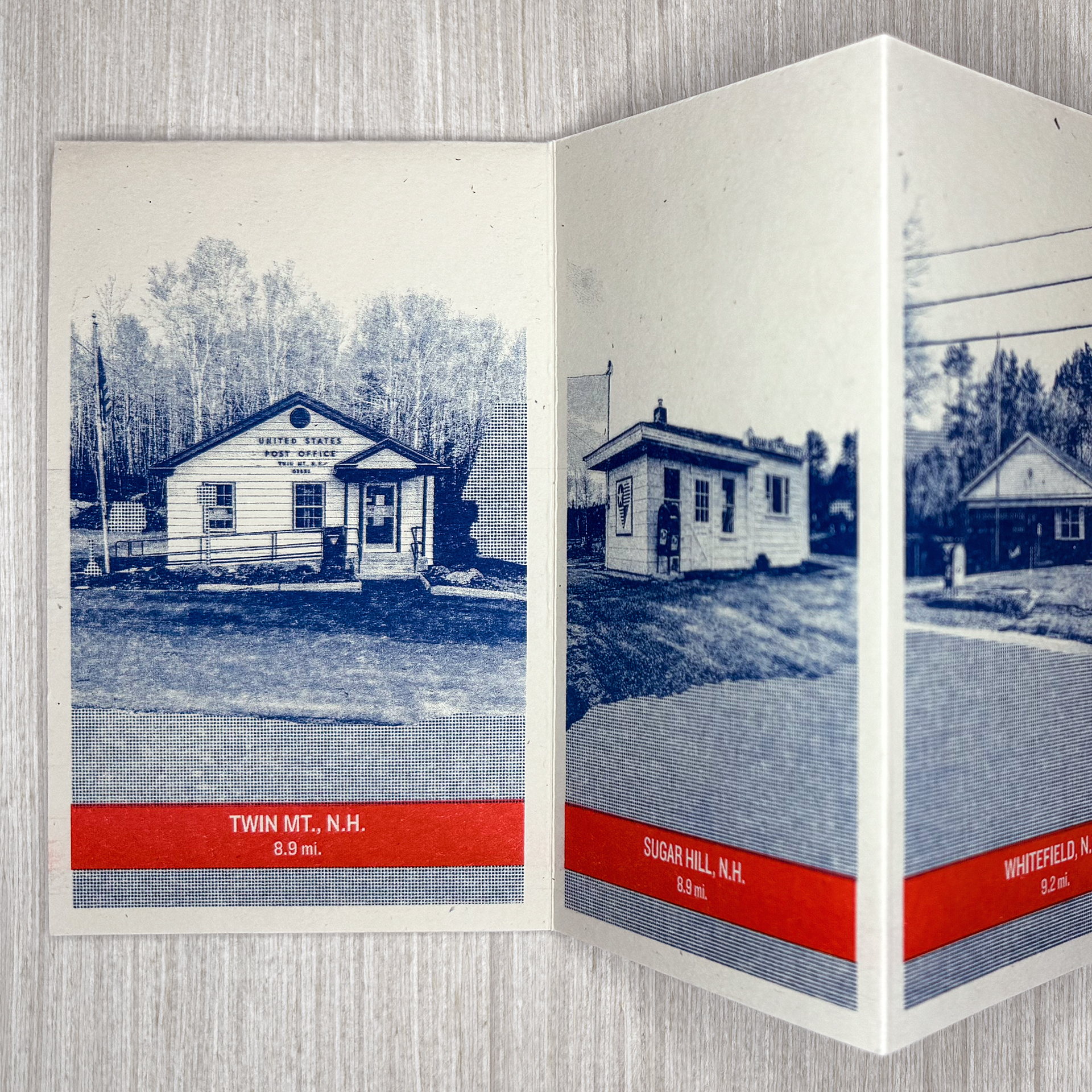

Josh Dannin

Post Offices I Hope To Know

Single sheet risograph pants book

5.85”x3.65” (closed)

2020

Originally designed and published on the web for free at-home printing via Quarantine Public Library.

BS: I’m impressed. That’s a lot to juggle and and it sounds like you’re providing a lot of service and a lot of good things while building a print-centered community.

JD: I’m just having fun. I have this stuff and I would much rather hang out with other artists and have people use it even when I can’t. I don’t have a great regular studio practice in terms of making my print work because I’d much rather build some furniture or something. I almost feel like my practice has evolved into being more of a shopkeeper. I still make my own work, of course, but I’m more comfortable in this role than in the role of an artist, whatever that even means.

BS: You’re the conduit, the facilitator. You’re the guy that can do things. You’re the guy that can provide things. That’s important.

Let’s backtrack a bit. We’ve been talking about letterpress and Riso sharing this space. I knew you first as a letterpress artist. It’s always been an important part of your practice and part of Directangle, so can you talk a little bit more, maybe in a philosophical way about how letterpress and Riso act as complementary tools in the shop? How often are your residents combining the two mediums or how much are you allowing play when you’re inviting in the public? What do you see as their relationship in the history of of commercial printing and the way print as an art form grows from that practical foundation?

JD: This wave of Riso craze feels a lot like you know the letterpress wave that happened you know some years prior. It’ll be interesting to see, because straight up, I don’t think that a Riso could survive in someone’s basement unused for 50 years in the way that you can find letterpress stuff. One of my presses literally came out of an open shed in Alabama. A Riso couldn’t take a weekend in the shed. So I think that it’ll be interesting to see how that repurposing pans out long term. There’s definitely a parallel between this history as means of production, which runs all the way through printmaking, of course, but in this case, both things are very much utilitarian tools to duplicate en masse and are now being co-opted by artists. That’s like the theme again and again. It’ll be interesting to see how this wave continues. There’s a different directness to the accessibility of Riso. That also might be generational based on the technological side of it and its relationship to computers and the ability to use it as a computer tool whereas you know letterpresses is slower and more tedious and there’s like more on the front end, right? I really like trying to make Riso as slow as I can, which is why I like working with it in a more analog, collage-based manner.

I guess it’s apples and oranges but in terms of how it coexists here in the shop, we do have people that put the two together and I really like that. I’m not set up in the way that a community printshop might be able to accommodate many different processes. I’m a little more focused space, based on my relief printing background, initially really focused on letterpress based equipment, and then falling into the Riso thing. They kind of have their designated areas around the shop but whenever I work with artists that I’m doing a collaborative project with, I’m really interested in–not exactly pushing that potential because I don’t want there to be pressure no pun intended– I think that there’s like an interesting potential to see what may come of it just with the access. While we have a lot of artists to come through as residents that are like specifically seeking access to a Riso printer or access to these colors or access to this size Vandercook or whatever I think there’s also plenty of people that are looking for a space that has these things and what may happen if you’re like surrounded by all this stuff. Some of the stuff that has happened as a result has been interesting.

We have a small laser cutter in here and we just had an artist a couple weeks ago, Valeria Guillen, who did a really beautiful book that was using a combination of riso with laser cut elements in the same way kind of conceptually that you might approach combining relief printed marks with an alternative process or something like that. Looking back, there’s been some interesting play and outcomes from the two processes kind of coexisting. We have some projects coming up that I’m excited about that really may utilize the two. I think they both can function, of course, as means to like making a finished product, but also as really cool generative machines Riso can be a really cool rapid prototyper and so can a Vandercook. What happens when you take that layer that we print on the Vandercook yesterday and then cut it up and then put those components on the flatbed of the Riso? I don’t know. There’s potential for so much play.

Past resident Maddy Underwood printing on the Golding Jobber No. 7 2023 Web: munderwood.design IG: @mmmunder

BS: Here at SEMO, we ran a letterpress for a while, and now we’ve got the Riso in our Mini Fab Lab and it’s interesting because letterpress can be pretty intimidating to students since most of their media intake is on a screen and having something that’s so physical and so analog takes a special sort of student to jump right into that. With risography though the learning curve is really flattened and it’s really accessible. We can whip out multiple layers in under an hour so it’s much closer to their media experience.

At the last conference in Providence at Open Portfolio the sheer volume of student work that was being done with riso was kind of overwhelming. And that’s part of why I’m doing this interview with you, and we’re doing the risography show for Graphic Impressions because I’m seeing that trend really pick up for the students who have that access.

JD: I think you nailed it. It’s like the point of entry can be immediate. I think a lot about how a short form letterpress workshop could happen in a way that I would feel good about. Where I could bring a group of people in and we could go over enough stuff that something could come out of it. But I always feel like I’m overlooking important things so they wouldn’t then be able to just come back into the shop and work independently in a short workshop. I’m sure there are ways and successful models of that but it’s tougher. I feel like it’s challenging to do in one three hour workshop, which is why we have an entire semester of letterpress, right? But you can do so much with riso in a three hour workshop and give people the confidence to play independently. We have residents come in pretty frequently that are looking for an introductory, more formal workshop to get their bearings on the Riso. One of my favorite things is teaching an introductory three-hour workshop where there was an outcome and people were running the printer on their own by the end of that workshop. I don’t know if they were to come back two weeks later, there’d probably be some refresher needed. But in this setting where someone’s here for a week or a few weeks you don’t need to fit all of the play and that final outcome in a three hour window they can see the possibilities and then play indefinitely. It’s amazing how quickly people start applying it to their work whether or not they come prepared with something ready to go. There’s an opportunity to start making what can often be viewed as a nice finished piece in pretty short order.

Past residents Sydney Long and Arantza Peña Popo and one of three Riso printers at Directangle Press

2025

Web: sydneylongillustration.com / arantzapopo.com

IG: @sydneylongillustration / @_ara_pena_

BS: Can we talk a little bit about your solo practice? You’ve been talking about how you’ve embraced your role in the shop at Directangle. Can you talk a little bit more about how you balance your responsibilities at the press and then maintain your solo work? How do you feel those two arms of your practice complement each other and support each other?

JD: As I mentioned earlier, I’ve always had a more periodic practice in making my print work. My background’s in music originally so that’s still in my mind my primary creative output in a lot of ways. Music has influenced all of this. My first press I ever found was in exchange for me selling a snare drum. It’s all kind of moved from my music to this, so alongside that, I’m always bouncing back and forth between working with other people’s stuff, working with artists here, working on my own stuff. I’ve settled into what feels very comfortable for me in a project focused practice so when I have a project that I’m working towards, or if I get the opportunity to work on a show or work, I really dive in and focus on that as a specific thing.

There’s definitely a through line between all my work. There’s a conceptual and aesthetic through line for sure, but I’ve become really interested in working within a set of parameters whether that’s spatially and dimensionally or environmentally so that the past handful of larger projects that I’ve made on my own have been very focused. For example, having the opportunity to take over a storefront at Space Gallery in Portland, Maine as part of a book fair and seeing how I can play with riso or relief work in more of an installation form. I really liked using riso as a modular building block.

At the same time, the last gallery based solo show I had was all linocut and woodcut stuff because I need to work with my hands all the time. I’m not a particularly fast producer of things.

I feel like there’s always a few things kind of going around in the background. I’ve been working on a bunch of personal work that’s autobiographical family related stuff that has been produced in the form of small zine, one page book format like vignettes that will maybe amount to a larger project at some point.

Where it overlaps into the studio and the residency and stuff is we’re always surrounded by what’s happening around us. Even though the subject matter of a lot of the work I’ve been making is very focused, the way that I think about the production side of it is, intentionally or not, inevitably influenced by what’s happening around me here. There’s so many different things happening here constantly I feel like it’s impossible for it to not inform my practice. So it’s definitely a juggling act. I snuck in here this morning pretty early before the residents were working to run something on the press to make sure that I’m out of the way before the residents arrive. It’s very important to me to make sure that the space is available and open to whatever they want to be doing when they’re here. So when I have stuff to do, I either schedule it around the residency or I really make it a point to come in before or after folks are on press. I want to be here to support what they’re doing and not be something that they have to work around. That probably influences things as well. I don’t know if I work better or worse at 6am, but I do something!

Josh Dannin

Keams detail

Risograph mounted to poplar

10.5”x7″x0.75” each

2023

BS: Your art making time is about to get compressed again, because you’re about to become a parent.

JD: Yeah, we have a baby on the way very soon.

BS: Having kids and finding ways to work around them upped my productivity immensely.

I like the way you talk about your practice being sort of slow. It sounds very familiar. You know Hannah, my spouse. The way I explain our practices is that she’s a compulsive maker. It’s the way she experiences the world. If she’s not drawing it, she’s not remembering it. She’s not experiencing it. I’m compelled to make. My sketchbook practice is nearly non-existent. When I have a project, I am all the way in until it’s done. I need that external motivation to interact with an audience. I’m much more interested in being a facilitator as a curator and as coordinator of this. I feel more fulfilled putting other people’s art out than making my own unless I’ve got an opportunity to share it.

JD: Absolutely. I actually think about you two a lot because I spent time down at SEMO early on when that press was active. I think I was still in Pittsburgh at that point, but that was like pretty early on in working with artists and working in the workshop setting. Seeing you both working on doing your work and you’re having this great family life at the same time is– from the outside, of course, everything is more complicated than it seems–it’s really nice. We’re taking about six weeks off from the residency when the baby is born and at a certain point after however many months, there’s going to be a lot of similar things happening around here with a baby attached to me. I have this picture burned in my memory of Matt Hopson-Walker screenprinting with one of his sons strapped to his chest. For years I’ve thought, that’s going to be me someday. We’re excited in every way. Thinking about it through the lens of what the day-to-day is here, there’s something to me that’s really exciting about having our kid grow up surrounded by so many different people doing so many different things. We live in a fairly remote place a couple hours from some amazing cities but there’s a slow speed of life here and we really like it but to be able to still expose a little one to such a diverse population of people and ways of existing in the world, I feel like is going to be a cool thing to kind of see. I know I’m expecting to get very little sleep uh and have an even more selective project-based creative practice.

Josh Dannin,

After Keams

Risograph mounted to rigid foam board and poplar

16’ wide overall/dimensions variable within

SPACE Gallery, Portland, Maine

2023

BS: It’s good to hear that you were here attracted to having a family by seeing us work. I feel like it goes one of two ways. We’re either aspirational for a few or we’re tremendous birth control for a lot of others!

This interview is going to be part of what is typically called The Next Chapter interview series. So typically I’m interviewing people that are academics who are coming to the end of their teaching career and moving on in their solo practice. Part of my ambition for this was always to talk to people that are moving outside academia, too. Or they were in academia more heavily at one point at an early point in their career and made a conscious choice to move away from that path. You’re a good candidate for that because I know that you’re teaching at Dartmouth part-time still but Directangle is your primary focus. Can you talk more about how you made that decision?

JD: Early on when I made the decision to go to grad school I took a year off in between and did a bunch of traveling, bouncing around to different studios and I don’t think I ever had the goal of teaching as my career focus. I taught in grad school. I really loved it. Then I made the move to running my studio right after school as we talked about earlier and then the position that I had at St. Anselm College happened. When I first got there, it was this residency gig alongside this technician thing. The school funded it at one point for it to become a full-time position and I applied to it and I got the gig. At that point I had a two-two teaching load alongside some technician responsibilities. It was great it gave me some security, of course, it gave me benefits which I had never had and haven’t had since, and it allowed me to still support myself and and keep my studio practice going.

At one point, I told myself that if I was going to teach, I didn’t want it to be because I was applying and applying and trying to get a job, but rather because I was doing what I was doing

and somebody wanted me to bring that into their classroom. It was this ideal that someone will someday ask me to come teach. It sounds wonderful, right? That’s not the way the world works. The path I found myself on with Directangle and in the studio has made me a worthwhile candidate to be teaching the classes I am teaching. When I’m at Dartmouth I teach what I offer here. There’s a handful of us that offer a stacked print one, two, three class and we each have a little bit of a different focus and teach it in different ways, covering of course the focus components throughout. A lot of it though is directly informed by what happens here. I think that I’ve found that I really love teaching, but I like teaching enough that I’m enjoying it without occupying my entire life because there’s a lot of other things that I like, too. My ideal format for teaching, is the week-long visiting workshop where you have time to do stuff, you have time to connect with people and potentially make some friendships that will continue on. I think we met at Frogman’s, for example. That environment is the ideal thing.

Now I feel super fortunate that I have the opportunity to teach a course year at Dartmouth. I have really great colleagues, Tricia Treasy runs our print area and we’re on a quarter schedule over there, which I still haven’t figured out, mostly because I don’t understand the way the calendar works. Because it’s a quarter system summer term is just another term that happens to happen in the summer. It’s also the one time of year I don’t have to worry about driving in the snow. Trisha Treasy asked me at one point, would you like to teach this summer so you don’t have to worry about the snow? And I said, that’s a great idea. We have 10 week terms and I teach for 10 weeks from June to August. It’s awesome. It’s fast paced, but Summer’s still a little sleepier. I could have anywhere from six to 10 students so it feels similar to the workshop setting. You have to fit a lot of stuff in a 10-week term, but at this point in my life I enjoy it so much. The students are psyched and we get to play with cool equipment. We have a really amazing book arts workshop on campus run by Sarah Smith that is outside of the School of Art in the library so they get into letterpress book art stuff on their own terms instead of being told they have to do it, which is kind of an interesting scenario. I have like 10,000 tons of equipment so maybe one of them will catch the bug!

It’s funny thinking about myself relative to a feature that is often folks retiring. I absolutely made a conscious choice that I am not teaching full time, though I don’t know how that works. Like I said, my background is in music so I grew up working in drum shops and restoring drums and collecting and working with vintage equipment and stuff. Frankly, when I need something, if we’re having a rough month in the studio and I need to get more ink or whatever, I have an inventory of so many drums that I literally go to my collection and choose one I haven’t used in awhile and I’ll sell it. That will get me by. It’s a strange choice in retirement plan perhaps, but there is an immediate crossover between the way these weird things have influenced each other. I would not say that I have financial security. I pay the bills. We have a really really fun, positive thing happening here. Love where I live. Love my family, work with great people, and everything takes care of itself. Never going to be rich. Don’t know if I’ll ever be able to retire, but I’m happy as hell. It’s about finding whatever version works, we definitely have a two income household. I absolutely could not do this without my partner. It works well together, our existence here, but frankly not sure if this could work if I was somewhere else.

BS: Your situation sounds enviable to me. This is exactly why I wanted to talk to you and why I wanted to sort of push this feature in this direction because higher ed is in such a precarious state right now and honestly has been for quite some time. I think it’s good to hear from people that have found a different path and have integrated teaching where they want it, but haven’t been reliant on that system. I think that’s really important now because I think increasingly the plethora of MFAs we keep producing see that the gigs are not necessarily going to be out there in the future, so they need to find another way.

JD: There are definitely times where it’s like, you know, what am I doing? Like everyone else, I have plenty of student loans and if I was really focused on making sure the government got every cent of that I probably wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing. But I decided a long time ago that if I thought about that I would have my head in the sand or something like I just couldn’t do this. You’re making some decisions to prioritize one thing over the other thing. I feel very fortunate that things have shaken out the way they have. There’s been ups and downs and it’s been a lot of work. I’m like a mechanic, I feel like. I really feel like my primary job is a mechanic. My undergrad professor, Evan Summer, used to tell us all the time that the largest part of being an artist is the business side of it. I spend a lot of time bookkeeping and a lot of time doing other stuff that for a lot of people may be unattractive. I don’t know. I really like that it’s different and even though I dread it as I’m doing it, I’m like, oh, now I get to like go to a cafe and stare at QuickBooks for a while, but there’s not a deadline with that, unless it’s tax season.

I feel super lucky in general to be in this position. Grateful for all the people that even consider checking the studio out, and now that come through and are part of our community. We have this ever-expanding extended family of artists!

BS: It sounds like a lot of what you’re saying is, if you want to do this, you’ve got to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. The best way to be comfortable being uncomfortable is being in a place where you can be comfortable in that place then the reality of the art situation has to fall in around that. I think that’s good advice.

JD: It has to be said that everyone’s not in the position to dictate things in that way. I think if you’re really drawn to something, maybe you can’t just drive somewhere and make a move. That’s totally fine. Maybe it becomes a small group of friends that you bring together and y’all can do it together. Maybe there’s someone you met at an SGCI that you had this great conversation with at open portfolio and maybe you give them a call and ask if y’all want to meet where you’re both driving four hours and meet in the middle somewhere and hatch a plan. There’s always some kind of way. It may really suck and it may be easier for some folks and maybe harder for some folks but if you’re excited about whatever it is it’ll work out. I guess it’s like anything, if you throw it against the wall long enough at some point, some parts of it stick and that doesn’t mean that everything you start off with is going to stick but you adapt and you see what happens. I don’t know, it’s part of the fun.

BS: Listening to you in this conversation, I think the other thing that for folks to keep in mind is that make yourself as handy as possible so that when problems arise, you can be your own Fix It. If that means you have to do the research, do the research so that you aren’t having to pay through the nose every time something breaks.

JD: The upside is it’s easier to connect with a network of peers and experts now. Ultimately going back to this idea of community that we’ve said again and again and again, for resources, and for friendship, and therapists–be selective with your friend therapist because they have their own stuff as well–everyone’s supporting each other and it’s a beautiful thing.

You can get by through bartering and sharing,too. There’s so many ways that don’t have to be an exchange of currency.

BS: Thank you for your time, Josh!

JD: Thank you, Blake.